For decades, 1941's "Citizen Kane" has been hailed as one of the greatest -- and most influential -- movies of all time. Orson Welles' debut film, based on the life of newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst, started its first run in major cities in May 1941. But it was September 5 that studio RKO named "'Citizen Kane' Day" -- the day the film was released widely "at popular prices." Welles starred as the title character Charles Foster Kane, a businessman and attempted politician.

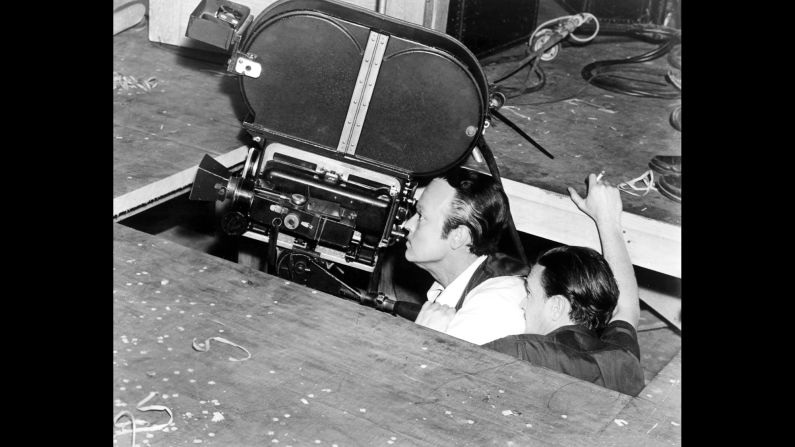

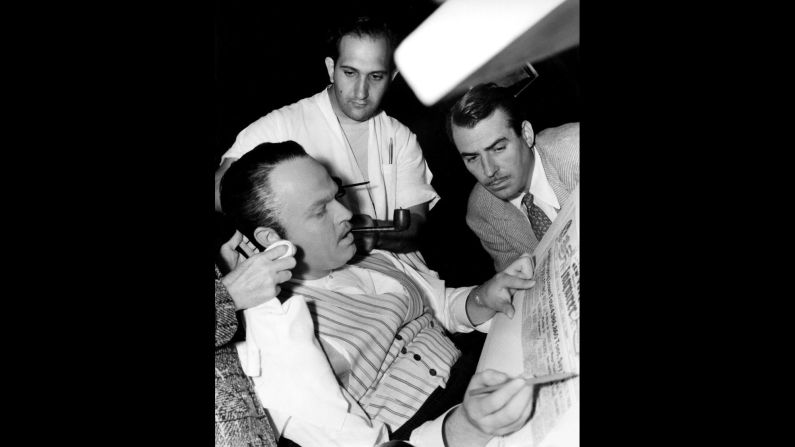

Welles, a 25-year-old phenomenon when he started filming "Kane," likened moviemaking to "the biggest electric train set a boy ever had." As with his theater and radio work -- some of the most innovative of the era -- the director was intensely creative when it came to "Kane." Perhaps his greatest collaborator was cinematographer Gregg Toland, right, who gave the film its distinctive deep-focus look and shot from unusual angles. "The greatest gift any director -- young or old -- could ever, ever have," Welles said of Toland.

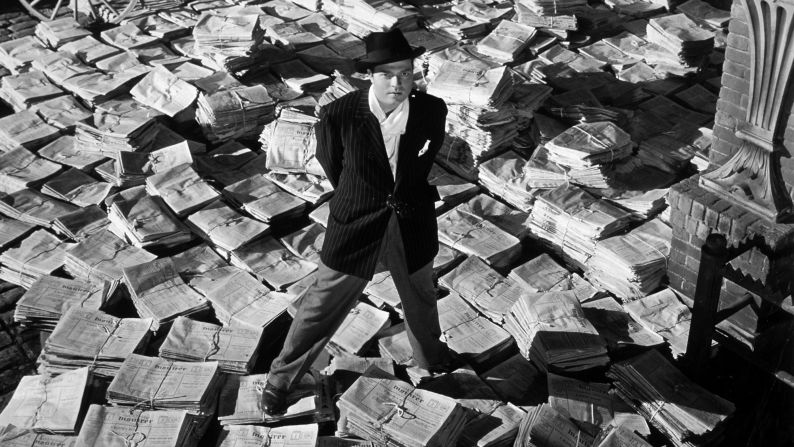

"Kane" has an unusual structure, with flashbacks and multiple narrators, but at the center is the main character, a youthful tycoon who drives his newspapers to be the most powerful in the land. The script was co-written with Herman Mankiewicz, who was a friend of Hearst's and knew the man well -- perhaps too well. Hearst and his associates were not happy with the portrayal.

Part of the sting likely came from the character of Susan Alexander, Kane's second wife played by Dorothy Comingore. In the film, Kane tries to make Alexander into an opera star. In real life, Hearst financed the films of his mistress, Marion Davies. (Davies had a flair for comedy, but Hearst liked to see her in dramas, for which she was miscast.) Welles denied the link, but it didn't help. Hearst's people tried to get the film stopped, and many theaters wouldn't run it.

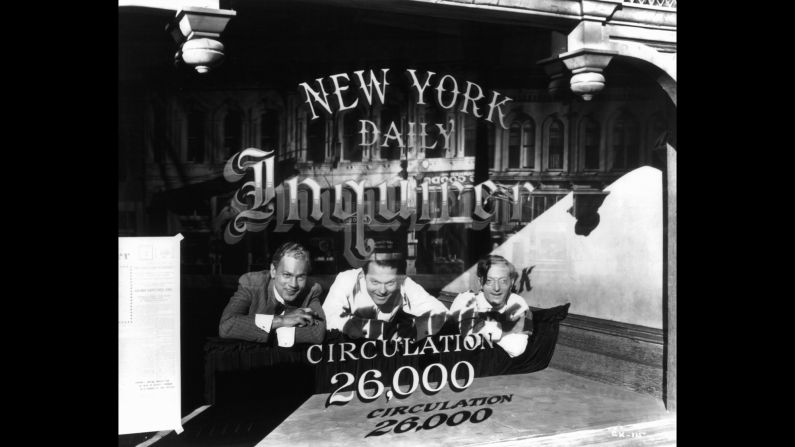

Two of Kane's closest friends in the film are Jedediah Leland (Joseph Cotten, left) and Bernstein (Everett Sloane, right). The latter stays with Kane through the decades. The former alienates his boss with a scathing review of Alexander. Both are interviewed by a reporter trying to bring some color to a newsreel biography of Kane's life.

Welles, shown here being made up for the film, was known as a "boy genius" when he started it. He'd dazzled Broadway with his stage productions, including an all-black "Macbeth," and he frightened the nation with his 1938 production of "The War of the Worlds." RKO gave him carte blanche for "Kane," and he not only directed and co-wrote the film, but he also produced it and hired many of his Mercury Theater colleagues for parts.

At one point during filming, Welles injured his ankle and had to direct from a wheelchair. That wasn't his only injury. According to a Turner Classic Movies article about the film, he gashed his hand in another scene and drank so much tea he was "the color of tannic acid." Good thing the film wasn't colorized. In fact, when CNN founder (and then-RKO library owner) Ted Turner wanted to colorize it, he couldn't. Turns out alteration was prevented by a clause in Welles' contract.

Ruth Warrick played Kane's first wife, presidential niece Emily Norton Kane. Warrick, who later became famous as Phoebe Tyler Wallingford on "All My Children," made her film debut in "Kane" and later collected "Kane" paraphernalia, including a replica of "Rosebud," the sled believed to be at the heart of the "Kane" mystery.

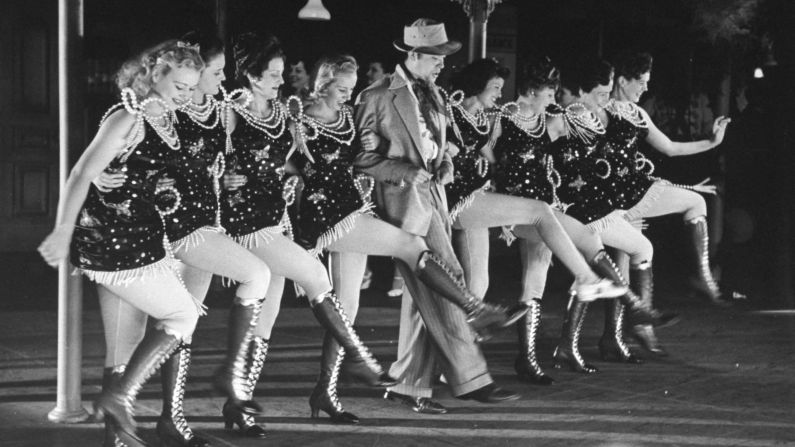

In the film, Kane goes from callow youth -- thrown out of some of the country's best universities -- to an invalid in his late 70s. As innovative as the film is, some of its staying power has to do with Welles' remarkable performance as Kane, as believable as a snide young man as he is an old tyrant.

Welles' future seemed boundless at the time of "Kane," but it can be argued that his movie career, though always interesting, peaked with his first film. His second, "The Magnificent Ambersons," was taken away and drastically recut; others flopped at the box office. He remained in demand as an actor, but he seldom starred in others' films. By the end of his life in 1986, he was as well-known as a commercial pitchman and talk-show guest as he was for his movies.

Despite terrific reviews, "Kane" was not a box-office success in its original run, and though nominated for nine Oscars, it won just one -- for Welles' and Mankiewicz's screenplay. However, over the years it regularly topped critics' lists and is now considered a classic. You can argue about the greatest film of all time, but one thing's for certain: The conversation isn't complete without "Citizen Kane."