According to photographer Nassim Rouchiche, the problems faced by immigrants in Algeria is one rarely addressed in public. For that reason, he has created Ça Va Waka, a haunting photo series that captures the lives of undocumented migrants living in Algiers, Algeria's capital. Ça Va Waka is on exhibition at the African Biennial of Photography in Bamako, Mali through December 31.

"Waka is originally from the English word 'walk'. It's an African way to say 'things are going to be all right.' I wanted to give this name because it gives hope," says Rouchiche.

"This issue of immigration in Algeria is pretty much never talked about. I hope that someday people will talk about it as a real issue and social problem in Algeria," he adds.

"This issue of immigration in Algeria is pretty much never talked about. I hope that someday people will talk about it as a real issue and social problem in Algeria," he adds.

Rouchiche notes that the men and women he captured on film are his neighbors.

"We live in the same neighborhood, and we see them every day, but don't have a real relationship with them." Many of his subjects, he adds, were resistant when he first proposed the project to them.

"It wasn't easy for them to let me into their lives in Algeria. But I was persistent, and I came to be friends with some of them. But even with this friendship, I couldn't go all the way into their world," he adds.

"We live in the same neighborhood, and we see them every day, but don't have a real relationship with them." Many of his subjects, he adds, were resistant when he first proposed the project to them.

"It wasn't easy for them to let me into their lives in Algeria. But I was persistent, and I came to be friends with some of them. But even with this friendship, I couldn't go all the way into their world," he adds.

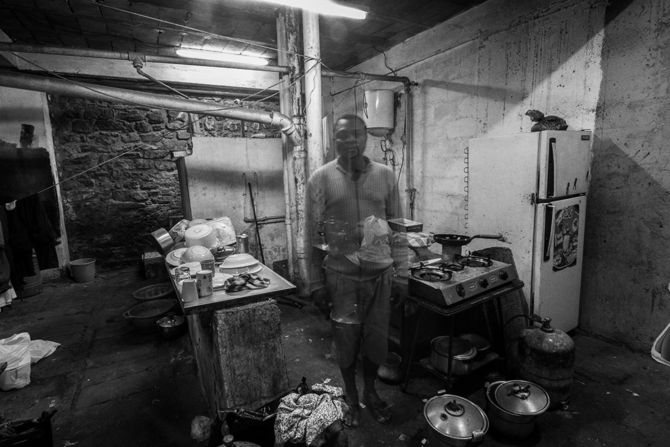

In the beginning Rouchiche took a more documentary-style approach to his photos. When two of his subjects were deported shortly after he photographed them, Rouchiche decided to portray his subjects as transparent.

"I want people to see them as ghosts. Ghosts are the ones who couldn't go to heaven or to hell. They got stuck between life and death. These people are like ghosts because they can't succeed in Algeria and they feel ashamed to go back home," he says.

"The series is shot at the Aero-Habitat, a quarter in the Algerian capital that looks like a vertical village. This community of migrants has chosen to inhabit this building because it gives them a living space, a place to work but also a hiding place. They can live here without exposure to the risk of identity checks that happen in the outside world," explains Rouchiche.

Rouchiche eschewed Photoshop to achieve his photographs' ghostly effect, relying instead on time lapse.

"To take the picture, I would have the person stay in the scene for a bit. Then he would leave the scene while the photo was still being taken, so you can see what was there after him. The time lapse was precisely chosen to leave just a trace of him in the picture," he explains.

"To take the picture, I would have the person stay in the scene for a bit. Then he would leave the scene while the photo was still being taken, so you can see what was there after him. The time lapse was precisely chosen to leave just a trace of him in the picture," he explains.

Rouchiche says he chose the settings for the photos spontaneously, and made the process a game he played with his subjects, many of whom migrated from Cameroon.

"I would just walk with them, and whenever I saw something I liked, I'd say to them 'n djoudjou,'" he says, referring to the Cameroon word for ghost.

"I approached each shoot like a game. Every time I said 'n djoudjou,' they had to stop to take the picture. It was a way to be pleasant with them and to play around."

"I would just walk with them, and whenever I saw something I liked, I'd say to them 'n djoudjou,'" he says, referring to the Cameroon word for ghost.

"I approached each shoot like a game. Every time I said 'n djoudjou,' they had to stop to take the picture. It was a way to be pleasant with them and to play around."

"My approach to this job was not to show that people are suffering, but to mention their status in Algeria and how difficult it is to live in their shoes," says Rouchiche, who hopes his photo series will help foster a more public dialogue about the plight experienced by his subjects.

"Some of these people came to Algeria 10 years ago but they still don't have a steady situation or stable life. Why are these people still outsiders even 10 years after coming to Algeria? It's a question I really want people in Algeria to answer."

"Some of these people came to Algeria 10 years ago but they still don't have a steady situation or stable life. Why are these people still outsiders even 10 years after coming to Algeria? It's a question I really want people in Algeria to answer."

Each photograph references how Algeria's undocumented migrants are barred from living fully in the present.

"Today they're here, but tomorrow they may not be. These people are even scared to have children in Algeria; they worry about how they can live with children if they don't even have papers. How will they get (their kids) to school and get health insurance?"

"Today they're here, but tomorrow they may not be. These people are even scared to have children in Algeria; they worry about how they can live with children if they don't even have papers. How will they get (their kids) to school and get health insurance?"

While some locals are happy to help out, providing the odd meal or job, Rouchiche believes these small acts are not enough.

"This is not the kind of help these immigrants need the most," he says.

"This is not the kind of help these immigrants need the most," he says.

Rouchiche thinks it's more important for locals to actually acknowledge the immigrants that share their world, so that their needs might be addressed.

"I want to talk about how people in Algeria don't take the time to talk about immigrants.. Society doesn't care about these people," he says.

"I want to talk about how people in Algeria don't take the time to talk about immigrants.. Society doesn't care about these people," he says.

Though life is tough for the undocumented migrant in Algeria, Rouchiche says that for many, going home is not an option.

"They can't just take a plane. You have to go by boat and through the desert of Algeria," he notes.

"They can't just take a plane. You have to go by boat and through the desert of Algeria," he notes.

Much of the interest in this project has been from abroad, says Rouchiche.

"I haven't been approached by anyone in Algeria yet to exhibit this work. But more than anyone, I want Algerians to see these photos," he says.

"I haven't been approached by anyone in Algeria yet to exhibit this work. But more than anyone, I want Algerians to see these photos," he says.

For Rouchiche, his work with Algeria's immigrant population doesn't end with this photo project. He is also working with the Tierney Foundation, a non-profit that helps emerging photographers in Algeria and South Africa.

"I want to keep working on the same subject, because for me this is not enough. I haven't done enough for this project yet. I want to keep talking about real matters that affect our society," he says.

"I want to keep working on the same subject, because for me this is not enough. I haven't done enough for this project yet. I want to keep talking about real matters that affect our society," he says.