What you need to know

• The Supreme Court is hearing oral arguments this morning in a major case that threatens to undermine the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Louisiana v. Callais centers on the creation of a second Black-majority congressional district in the state.

• While the dispute is focused on Louisiana’s congressional map, the outcome will have nationwide implications. The Pelican State is squaring off against voting rights groups who warn that undermining the Voting Rights Act protections for redistricting risks “wiping out minority representation and re-segregating legislatures, city councils, and school boards.”

• Going into the arguments, signals from the conservative majority have pointed to a potential reversal on the Louisiana map with a possible retrenchment of the landmark civil rights law.

Edward Greim, who fought IRS during Obama years, repping plaintiffs

Edward Greim, an attorney who fought the IRS during the Obama administration over its scrutiny of conservative groups, is speaking on behalf of the “non-Black” voters who sued over the current version of Louisiana’s map.

Greim, a Missouri native and 2002 Harvard Law graduate, argued the same case when the justices heard it previously in March.

Greim represented a group of Tea Party advocates in a high-profile, class action legal case alleging the IRS aggressively scrutinized conservative groups during the Obama administration. The case resulted in a settlement in 2017.

Greim is arguing on behalf of a group of “non-Black” plaintiffs who alleged Louisiana’s updated map violated the 14th and 15th Amendments, which were ratified after the Civil War.

Sotomayor stresses that race has traditionally been used in the redistricting process

Justice Sonia Sotomayor stressed at one point that race has traditionally been used lawfully in the redistricting process as she pushed back on Louisiana’s argument that it cannot be used to remedy violations of the Voting Rights Act.

“Race is a part of redistricting always… Race is always a part of these decisions, and my colleagues are trying to tease it out in this intellectual way that doesn’t deal with the fact that race is used to help people,” Sotomayor, the court’s senior liberal member, told Louisiana Solicitor General Ben Aguiñaga.

“Legislators might try to keep an ethnic community in one district. They might consider it to get a sense of which district to draw an incumbent into. They might review it to predict what kind of issues a district voter might be particularly interested in. They might use it to inform partisan goals,” she said. “We permit all of that.”

Roberts once called Louisiana's 6th District a "snake"

The congressional district that kicked off the current Supreme Court case is Louisiana’s 6th District, currently held by Rep. Cleo Fields, a Democrat.

The district slashes diagonally from Shreveport in the northwest of the state to Baton Rouge in the southeast for some 250 miles to create a district where Black residents make up some 54% of voters – up from about 24% under the old lines.

Earlier this year, Chief Justice John Roberts referred to it as a “snake.” That’s important because one of the traditional goals for mapmakers is to draw congressional districts that are “compact.”

“If you look at CD6, what does ‘reasonably compact’ mean?” Roberts said during the first arguments in March. “I mean, it’s – it’s a snake that runs from one end of the state to the other. I mean, how is that compact?”

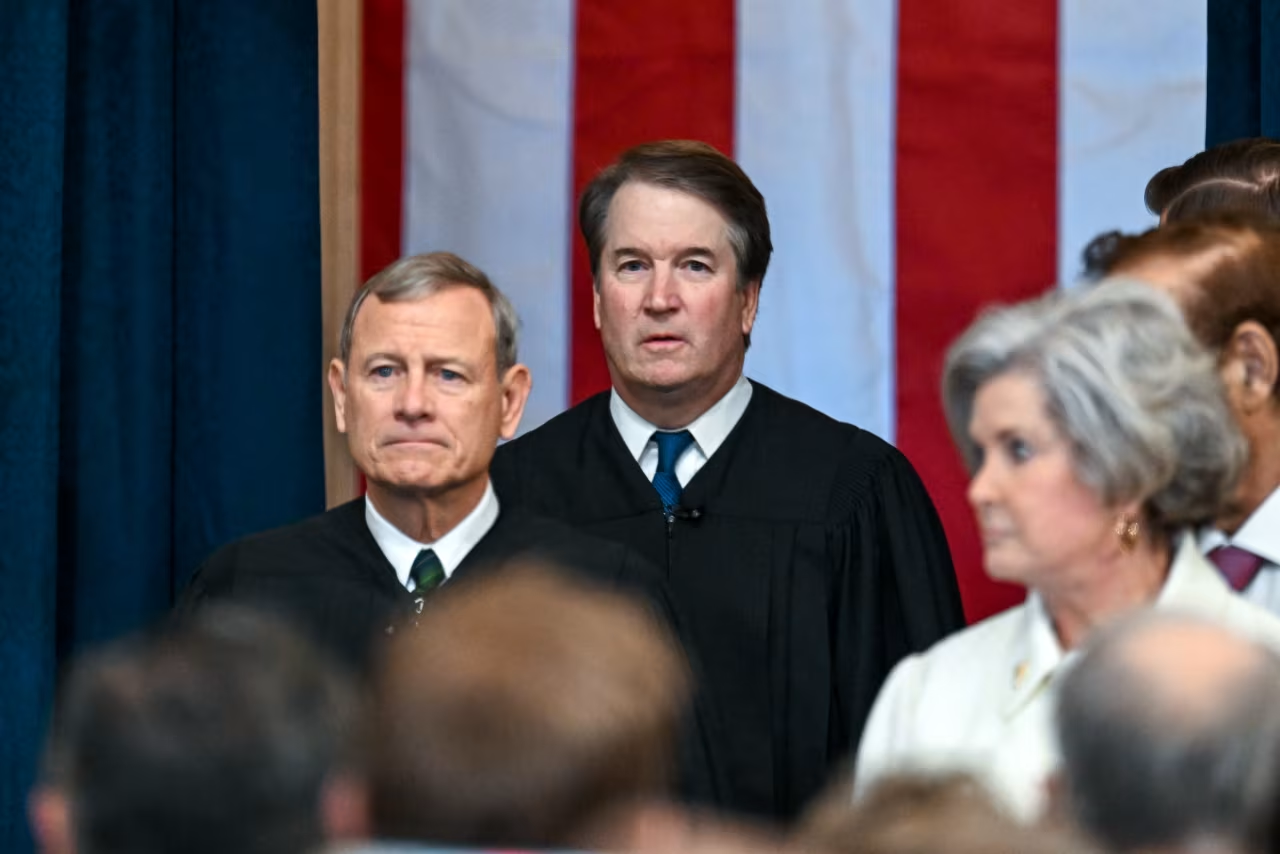

Conservative justices show early skepticism of Louisiana’s congressional map

Several conservative Supreme Court justices signaled skepticism over the creation of a second majority Black district in Louisiana in the early stages of oral arguments Wednesday.

In a mostly subdued series of questions, the conservative justices – notably Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh – asked questions that at least suggested concerns with Louisiana’s drawing of a second Black majority district.

It wasn’t until roughly 45 minutes into arguments that some of them began raising fundamental constitutional questions about the use of Section 2.

Kavanaugh was perhaps the most important questioner during the first round. At one point, he quoted from earlier decisions suggesting that “race-based districting” embarks the nation on a “most dangerous course.”

The Donald Trump-nominated justice also repeatedly returned to the question of whether states can rely on the Voting Rights Act to draw majority-minority districts indefinitely.

Ben Aguiñaga, former Alito clerk, is arguing for Louisiana

Ben Aguiñaga, the top appellate attorney for the state of Louisiana, is at the podium on behalf of the Pelican State.

A former clerk to Justice Samuel Alito and a Texas native, Aguiñaga has argued at the Supreme Court twice before, including once when justices heard this same case in March. He also argued on behalf of states who last year alleged that the government’s efforts to combat online misinformation amounted to a form of unconstitutional censorship.

Aguiñaga received his law degree from Louisiana State University in 2015 and clerked for US Circuit Judge Edith Jones on the 5th US Circuit Court of Appeals.

He spent a year as the chief of staff for the Civil Rights Division at the US Department of Justice during President Donald Trump’s first administration. He was an attorney at Jones Day for nearly five years before joining the Louisiana attorney general’s office in early 2024.

Attorney for Black voters tells Kagan that gutting Section 2 would be "pretty catastrophic"

When Justice Elena Kagan asked an attorney for Black voters in Louisiana what the “results on the ground” would be if the Supreme Court strikes down Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, the lawyer made no bones about how devastating she believed the outcome would be.

“Were Section Two to cease to operate in the way that you just described … what could happen? What would the results on the ground be?” Kagan, a member of the court’s liberal wing, asked Janai Nelson.

“I think the results would be pretty catastrophic,” Nelson responded quickly.

She continued: “If we take Louisiana as one example, every congressional member who is Black was elected from a VRA opportunity district.”

Key vote Brett Kavanaugh says race-based redistricting can’t last forever

Justice Brett Kavanaugh is pressing on a point that is central to the case: Whether redistricting that takes race into account should be allowed to carry on indefinitely.

It’s potentially a signal that Kavanaugh is skeptical of the position raised by Black voters. The Supreme Court raised a similar point in striking down affirmative action admissions policies in 2023.

“This court’s cases, in a variety of contexts, has said that race-based remedies are permissible for a period of time,” the conservative justice asked. “But that they should not be indefinite and should have an end point. What exactly do you think the end point should be?”

Janai Nelson, representing the Black voters in Louisiana, has argued that the Voting Rights Act has a time limit built in, because states must redraw their maps with a new census every decade.

Have Voting Rights Act suits run amok?

One of the arguments Louisiana and critics of the Voting Rights Act is making is that the confusion around how to apply the law in redistricting has spurred a bevy of lawsuits, even as minority representation has increased and housing segregation has decreased.

That line of attack has drawn some interest from conservative justices in the past.

But an interesting brief from the Voting Rights Initiative at the University of Michigan Law School has made the opposition point: The number of vote dilution lawsuits based on Section 2 of the VRA, it says, has gone down.

Janai Nelson, representing the Black voters in Louisiana, pointed to that brief early in her arguments on Wednesday.

According to that brief, the number of Section 2 vote claims has almost halved over recent decades.

“Courts today adjudicate far fewer Section 2 vote dilution claims, and find far fewer Section 2 violations, than in prior decades,” the brief claims.

But... John Roberts questions whether previous Alabama precedent applies

In his typical understated way, Chief Justice John Roberts threw some early shade in his opening question on the idea that Supreme Court already decided this case in favor of the Voting Rights Act two years ago.

His pushback is important because the attorney for Black voters in the case noted the court just upheld the Voting Rights Act in a similar redistricting case dealing with Alabama two years ago. Roberts was having none of it – suggesting he doesn’t believe the Alabama case resolves the issue.

Roberts supported the Voting Rights Act in the Alabama case. His vote is likely up for grabs in the Louisiana appeal.

In that case, Roberts said, the court “considered Alabama’s particular challenge” not necessarily one that would apply to Louisiana.

Didn’t SCOTUS just look at this two years ago? (A: Yes)

If the Supreme Court ultimately sides with Louisiana and overturns a key provision of the Voting Rights Act, the outcome will beg an obvious question: Why didn’t the court do it two years ago?

Way back in 2023, a 5-4 majority of the high court ordered Alabama officials to redraw that state’s congressional map to allow an additional Black majority district. That outcome came even though Alabama raised some of the same arguments then that Louisiana is raising now.

That decision came as a surprise, after oral arguments suggested a majority was likely on Alabama’s side.

And some of the language in that opinion, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, is particularly striking when viewed alongside the arguments Louisiana is making in its appeal. Louisiana, for instance, has come out strong for the prospect that the Constitution requires a colorblind approach to redistricting.

“The contention that mapmakers must be entirely ‘blind’ to race has no footing” in the court’s Voting Rights Act precedents, Roberts wrote in 2023.

“The line that we have long drawn is between consciousness and predominance.”

It would take only one justice to switch votes in that case, Allen v.

Milligan, to land on a different outcome for Louisiana.

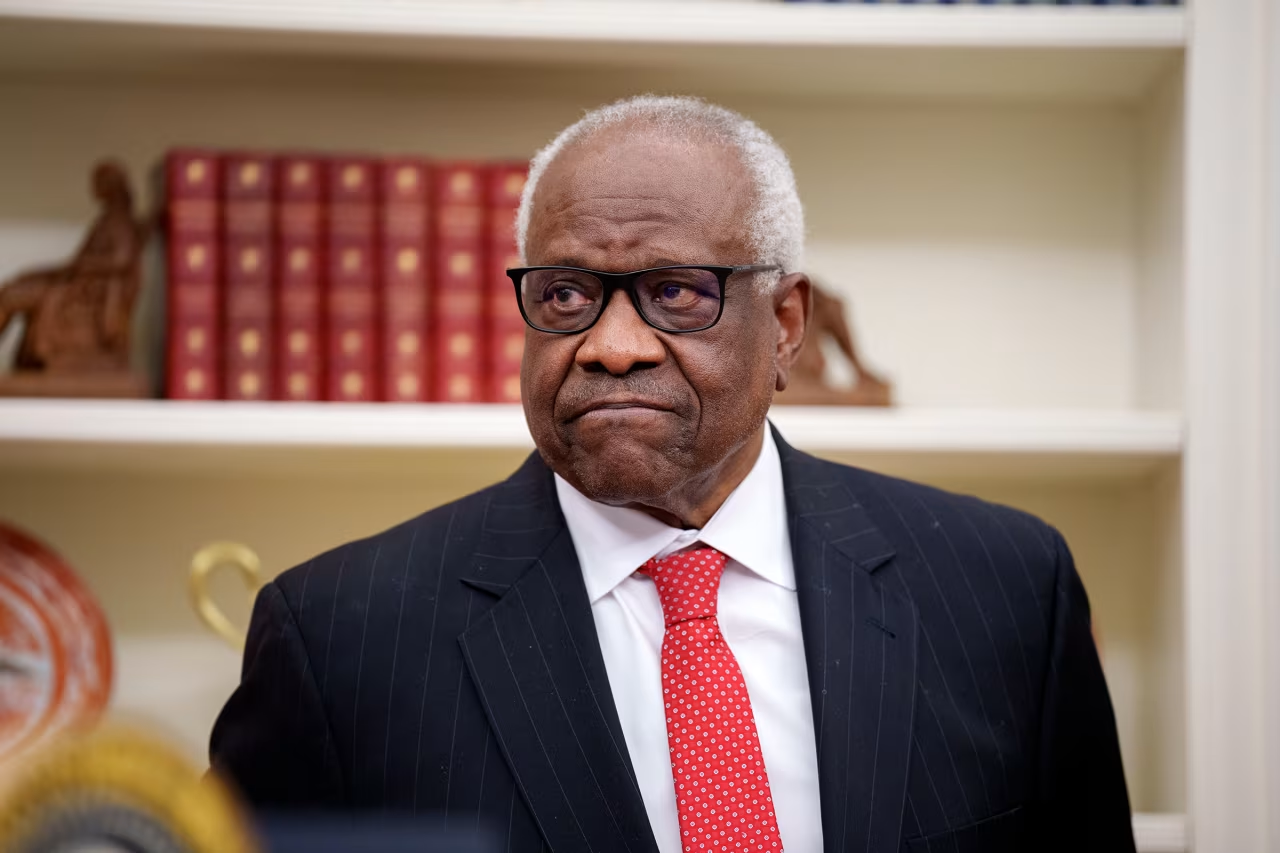

Thomas, expected to side with Louisiana, asks first question in major Voting Rights Act case

Justice Clarence Thomas, a member of the court’s conservative wing and its most senior associate justice, is asking the first question – which he almost always does these days during oral arguments at the Supreme Court.

Thomas started off with a series of technical questions about the original court order striking down Louisiana’s first map. Previously, the conservative justice has expressed skepticism about that court’s decision – and he reiterated some of that skepticism on Wednesday.

“There was never a full merits determination,” Thomas said.

Thomas’ position on the case is the clearest of all the nine justices. When the court declined to decide the Louisiana redistricting appeal earlier this year – holding it over for a second set of arguments – Thomas wrote separately to say he would have decided right then and there that the Voting Rights Act could not be used to justify creating another majority Black district.

Thomas wrote then that the way a majority of the court has approached the issue is “broken beyond repair.”

It’s a point Thomas has been making for years. He has been joined at various times by fellow conservative Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett.

Janai Nelson, head of NAACP's Legal Defense Fund, defends Louisiana’s map as arguments begin

The unusual posture of the Supreme Court’s major Voting Rights Act case means only one attorney will stand before the justices on Wednesday to defend Louisiana’s congressional map. That task fell to Janai Nelson as oral arguments began just after 10 a.m. ET.

Nelson, a Fulbright scholar and former law professor, is the president and director-counsel of the storied NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

Nelson is representing a group of Black voters who challenged Louisiana’s first map under the Voting Rights Act. A lower court found that first version likely violated the VRA and that is what prompted the state to draw the second map, which is now at issue before the Supreme Court.

Nelson received her law degree from UCLA and clerked for US Circuit Judge Theodore McMillian on the 8th US Circuit Court of Appeals and US District Judge David Coar in Illinois.

Voting Rights Act supporters gather in front of court

Several dozen people gathered outside the Supreme Court on Wednesday an hour before historic arguments over the Voting Rights Act were set to get underway, with most appearing to support letting the landmark civil rights era law stand.

Many held handmade signs that read “Fair representation for all” and “Defending Voting Rights” as they gathered in front of the court’s west façade. There were also several signs with photos of the late civil rights icon Rep. John Lewis.

The rally, which will continue throughout the morning, was organized by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, the League of Women Voters and other voting rights groups.

Ashley Shelton, the founder and CEO of the Power Coalition for Equity and Justice from Louisiana, one of the organizers, said: “We know the stakes have grown, that’s why you all are here, because this case has become not just about the state of Louisiana, but it has also become about this country and whether or not Black and other voters of color will have a fair opportunity to have their voices represented.”

Eric Holder: America faces "greatest attack" on voting since Jim Crow

Former Attorney General Eric Holder said Wednesday that America is facing the “greatest attack on the right to vote since Jim Crow,” as he called on the Supreme Court to uphold Louisiana’s current congressional map.

“The court must make it clear that violating the voting rights of American citizens will not be tolerated, and it must do so by permanently reinstating Louisiana’s Voting Rights Act-compliant map,” said Holder, a former attorney general during the Obama administration and the chairman of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee.

But Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill said before the arguments Wednesday that the “entire system” of redistricting that the Supreme Court has endorsed in past opinions is unconstitutional because it relies on race to draw new majority-minority districts.

“It’s time for the courts to stop forcing us to separate our voters by race,” said Murrill, a Republican. “Our Constitution prohibits the sorting of Americans into voting districts based on their skin color.”

What is Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act?

The case before the Supreme Court on Wednesday deals with what’s known as Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which was initially enacted by Congress in 1965 and signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson.

The provision originally barred any “voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure” that worked to “deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

In a 1980 decision, the Supreme Court effectively concluded that only intentional discrimination violated the law. That decision drew significant criticism. The New York Times wrote at the time that the outcome was “the biggest step backwards in civil rights to come from the Nixon Court.”

Two years later, Congress amended the provision to sweep in voting laws that had a discriminatory effect, regardless of whether challengers could prove intent. The new language, crafted by the late Sen. Bob Dole, a Kansas Republican, barred any voting practice that “results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”

That subtle difference – adding the words “results in” – was enormously consequential, because it allowed voting rights groups to challenge laws that had the effect of discrimination even if those groups could not demonstrate intent. Now, more than four decades later, the court is wrestling with whether Congress was within its constitutional authority to do so.

President Ronald Reagan signed the changes into law in 1982.

Supreme Court has weakened the Voting Rights Act in past decisions

If the Supreme Court sides with Louisiana in this latest legal fight over the Voting Rights Act it will be only the latest instance in which its conservative majority weakened the landmark 1965 law.

Just over a decade ago, the court’s conservatives struck down a section of the Voting Rights Act that required mostly southern states with a history of racist voting policies to get “preclearance” from the Justice Department before making changes to state voting laws, including new congressional maps.

At the time, Chief Justice John Roberts explained that “our country has changed” for the better. And that the deplorable conditions that prompted Congress to pass the voting rights law in the 1960s “no longer characterize voting in the covered jurisdictions.”

The court also stressed that another section of the law – Section 2 – would remain on the books to deal with future problems. That is the section of the law now at issue in the Louisiana case.

More recently, in 2021, the court let stand two Arizona provisions that dealt with “time, manner, or place” voting restrictions, making it harder for voting rights groups to challenge those provisions under the Voting Rights Act.

Why Brett Kavanaugh is a key justice to watch

When the Supreme Court last considered the issue of race and redistricting, conservative Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts joined with the court’s three liberal justices to uphold the provision of the Voting Rights Act that’s now at issue again.

But Kavanaugh signaled in a concurring opinion that his vote could be gettable for Louisiana and other critics of the law, all of whom have leaned heavily into a point the Trump nominee has repeatedly made.

Kavanaugh has picked up on the idea that, even if Congress was operating within the Constitution to require race-based fixes to discriminatory congressional maps when it enacted the Voting Rights Act in 1965 (and then amended the law in 1982) there must be a time limit on those fixes if they involve taking race into account.

“The authority to conduct race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future,” Kavanaugh wrote two years ago.

The issue of a time limit was a key element of the court’s decision that same year to strike down affirmative action policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina. And it’s an argument that Louisiana repeatedly focuses on in its latest briefing at the high court.

The reasoning in the affirmative action decision, Louisiana wrote, “all but disposes of race-based redistricting.”

“There can be no dispute that” the provision at issue in the case “is neither ‘a temporary matter’ nor ‘limited in time.’ That mandate has existed for more than four decades – and there is no end in sight,” the state wrote.

Supreme Court to hear major voting case with echoes of civil rights era

The Supreme Court will hear arguments Wednesday in one of its most significant cases this year, an appeal that could have profound implications for the resiliency of the Voting Rights Act and that could significantly reduce minority representation in Congress and state legislatures across the country.

At issue is whether states may “fix” discriminatory congressional district boundaries that often harm Black voters by creating new majority-minority districts – a process that, while it helps minority voters, takes race into account and that some conservative critics say is unconstitutional.

The case centers on the six congressional boundaries drawn in Louisiana following the 2020 census. Though African Americans make up about one third of the Pelican State’s population, only one of those six districts was initially represented by a Black member of Congress. A federal district court ruled in 2022 that the map likely violated the Voting Rights Act.

In response, Louisiana redrew its map to create a second majority-Black district. But that new map prompted a second lawsuit from a group of White voters who alleged the state violated the equal protection clause by relying on race to fix the first map. A lower court agreed, and Louisiana appealed to the Supreme Court arguing it was between a rock and a hard place.

The state now says it should never have been required to draw that second map and that race shouldn’t play a role at all in redistricting.

If the court agrees, it could wipe out the only concrete remedy Black voters have to fight back against violations of the Voting Rights Act: A court order pushing the state toward drawing a second Black-majority district.

If it all sounds familiar that’s because the court already heard a version of the case back in March. In June, the court took the highly unusual step of holding the case for a second round of arguments.