Thinking about the possibility of pathogens on our food may seem unappetizing at best and downright scary at worst, but the headlines warning of foodborne illnesses never seem to stop.

In late July, for example, Western Washington saw a lethal outbreak of listeria, a pathogen often transmitted through contaminated food. Five people in their 60s and 70s who had already-weakened immune systems were hospitalized. Three of the five died.

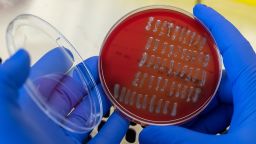

Dr. Catherine Donnelly, professor emeritus in the Department of Nutrition and Food Sciences at the University of Vermont, has spent much of her career studying Listeria. In the public health effort to stamp out foodborne illnesses, Listeria is a pathogen of particular concern, she noted, as it has a relatively high rate of hospitalization and death.

Listeria is just one of a host of pathogens that, from time to time, contaminate foods and infect the consumers who eat them. Salmonella, hepatitis, E. coli and Cyclospora, too, have been the cause of major outbreaks. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 48 million people contract foodborne illnesses each year in the US, 128,000 are hospitalized and 3,000 die.

This leaves consumers in a quandary: how to feed ourselves and our loved ones without risking illness. Even harder to contend with is the fact that the food products most susceptible to contamination are often those we eat for their health benefits – produce items.

“The CDC published a study about 10 years ago looking at specific commodities that were attributable to foodborne illness,” says Donnelly. “Produce led the list; about 46% of the foodborne illness that we saw in the US could be attributable to produce. And within the produce category, leafy greens are one of the leading causes of illness.”

That’s not to say that contamination can’t occur in processed foods. It can — and does.

Last year, four infants fell ill — and two eventually died — from Cronobacter sakazakii, a bacteria that can cause a rare but potentially lethal infection in newborns and is a known contaminant of powdered infant formula. These cases set off a nationwide recall of the formula and prompted the temporary shutdown of a major manufacturing plant in Michigan. Formula, which was already in short supply due to supply chain issues, was out of stock at many stores across the country.

According to 2018 data from KFF, more than half of infants receive formula either exclusively or supplementarily in their first three months. The shortage left many families desperate, with little to no safe options for feeding their babies. Some resorted to dangerous alternatives such as making homemade formula.

In the wake of this crisis, calls have abounded for diversification of the infant formula industry, as well as sweeping food safety changes at the US Food and Drug Administration to insulate the nation from future shortages like this.

But Donnelly has another idea: make sterile, liquid infant formula available and known to more families.

“If something is ‘sterile’ it means that the product has undergone a process during which any potential pathogens are inactivated,” says Donnelly. Powdered formula, which is not sterile, has microorganisms in it by virtue of the production process. Sterile liquid formula, by contrast, is microorganism-free, greatly reducing the risk of Cronobacter infection.

“We need to make those sterile products more widely available for new mothers and increase awareness that those products are alternatives to breastfeeding. Of course, sterile products are also more expensive than powdered formulas, so part of increasing availability means making them affordable to parents.”

Donnelly spoke with CNN Opinion about what consumers should keep in mind about foodborne illness. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

CNN: Foodborne illnesses are often linked to produce. In the process of getting produce from the farm to our kitchen tables, where do disease-causing organisms worm their way into our foods? And why are leafy greens particularly susceptible to that contamination?

Catherine Donnelly: When you harvest produce, wash it and chop it up, moisture is released. Then you put it in a bag, and it undergoes refrigerated storage in that nice, moist environment. If there are any pathogens that have been carried with that produce, the moisture helps them survive. And when they’re consumed, they can cause illness.

I have colleagues who are food microbiologists who say, “I would never eat bagged produce.” But I’m one of those consumers who loves the convenience of bagged produce, so what I do is pay attention to active outbreaks or recalls going on.

And regarding leafy greens in particular, we like to consume them because they’re nutritious. Well, they’re unfortunately also nutritious for bacterial pathogens. The other problem with leafy greens is that they’re very fragile products, so we can’t do too much to decontaminate them, because then you ruin the very product that you want to consume.

CNN: I’m picturing my local grocery store and the options that might be available if I were shopping for vegetables. I might have the option of picking broccoli florets that are already bagged and on the shelf or a head of broccoli that’s fresh and not bagged. Would it be correct to assume, then, that that second option — the unbagged, fresh produce — might be less likely to pose a health risk?

Donnelly: There are so many factors that go into answering that question. Where was the produce grown? And under what conditions?

There are so many ways that produce can become contaminated. For instance, I’m sitting in Vermont, and we’ve just had major flooding around our area. You look at water runoff events, and you have to ask: Where is that water running from? Is it adjacent to dairy farms that carry pathogens like E. coli? Then you have to consider: Is the produce domestically produced? Is it imported from outside of the US — and, if so, is it sold by a company in the States that does an excellent job with testing, sanitation and monitoring?

Most companies that are selling products in grocery stores have websites where consumers can look for information on products. And retailers are required to post notices so that consumers will know if there’s an active recall of a product. Consumers can also keep an eye on the FDA and CDC websites for recalls.

CNN: What advice do you have for consumers to navigate those questions you raise?

Donnelly: My advice is always: Buy products from places that you trust. I think shopping at a chain where you know the store is doing their due diligence is important.

Consider buying products closer to home — from farmer’s markets, for instance, where the time from the harvest to consumption might be narrower than for products that are centrally produced, bagged and shipped great distances. That can help reduce the risk of being exposed to pathogens. When I purchase leafy greens, if there’s a hydroponic option, I tend to gravitate towards that because there are more controls that can be put in place in hydroponics than out in a field.

But I want to emphasize that we have a really good public health system in this country. And so, the FDA, the US Department of Agriculture, the CDC and local health departments are all working collaboratively to keep track of what items might be causing problems out there.

CNN: Lettuce and other bagged greens are often labeled “triple-washed,” which leads consumers to think they don’t need to wash them. Do you think there’s a benefit to washing bagged produce? Could doing so reduce the risk of contamination?

Donnelly: Personally, I do not wash triple-washed produce for a couple of reasons. The first is that you are unlikely to wash away any bacteria through washing; it removes dirt but not necessarily microbial contaminants. Secondly, you are introducing additional moisture, which may accelerate the deterioration of the triple-washed greens.

CNN: How serious do cases of foodborne illness tend to be?

Donnelly: Many of the pathogens we deal with will make you sick for a while, but they’re not going to kill you.

But there are different considerations for the most vulnerable demographics: certainly for infants or young children or the elderly. The choices that I would make for myself might be different than for my elderly parents, or my friend who’s undergoing chemotherapy for cancer.

I have a lot of experience with the pathogen Listeria. For individuals with functional immune systems, Listeria is not going to cause a problem. It’s really those individuals who are immunocompromised in some way who are at greater risk.

For those individuals, the good news is there are a host of products that might be safer alternatives. Cold cuts, for instance, have been linked to a lot of outbreaks. But we now can reformulate some of those products and add in sodium diacetate, which is a preservative that slows the growth of Listeria. So, if someone wants to consume cold cuts but has compromised immunity, that might be a better choice.

CNN: That’s particularly interesting because there’s been a lot of attention paid to the higher health risk associated with foods that have undergone a higher level of processing. But you bring up a really great point that the processing of packaged meats may actually protect the products from pathogens. So, for people who are immunocompromised, or who might be particularly vulnerable to illness from food contamination, perhaps it’s not quite as simple as saying: Processed food is bad, fresh food is good.

Donnelly: Exactly. Take a delicatessen. That slicer might have been used for lots of different products. If one of those products is contaminated and then you slice other foods on it, everything becomes contaminated. And we’ve seen outbreaks that have happened through exactly those means.

CNN: Toxic chemical contamination has also been making headlines. Blueberries made the Dirty Dozen, the list of nonorganic produce contaminated with the most pesticides, and US kale samples have been found to contain concerning levels of forever chemicals. How should we weigh the health benefits of foods like blueberries and kale— chock full of antioxidants — against the harm of the dangerous chemicals we’re potentially eating along with them?

Donnelly: With respect to pesticides, there’s a lot of work that goes into approving the uses of these pesticides and their application to agricultural commodities in the US. The way I look at it is: Without the pesticides, you’re going to have more insects and more damage to crops. If the insects are carrying pathogens, that can cause infection and make you sick.

So, it’s a kind of a risk-benefit equation. I know there has been a lot of attention paid to the role of pesticides and diets of young children, and I certainly think that it’s an area where we need more oversight and more research.

CNN: Are there things that you think could be done differently at the national level, maybe more diligently, to avoid food contamination?

Donnelly: In 2011, under President Barack Obama’s leadership, Congress passed the Food Safety Modernization Act, which focuses on getting preventive measures in place so that we can prevent foodborne illnesses from happening in the first place instead of reacting to problems once they’ve occurred.

But especially with leafy greens, there are still some challenges. We need to be looking at water quality standards, intrusion of animals into growing areas and requirements for individuals responsible for harvesting. The Leafy Greens Marketing Agreement is providing some great leadership and recommendations to growers on how we can make these products as safe as we possibly can.

CNN: How is climate change affecting food contamination?

Donnelly: We are seeing foodborne illness outbreaks as a direct result of change in the climate. Ocean water temperatures are increasing at a breathtaking pace. It’s truly frightening.

The incidence of some pathogens has increased as ocean water temperatures have risen. We’re seeing Vibrio, a pathogen that lives in water, thriving in the warmer environment. In cold waters, like Alaskan or Canadian waters, we never saw Vibrio before. Now, because the oceans are warming, we are seeing Vibrio in these places, and it’s impacting the seafood we eat. In some places where we used to be able to consume raw oysters, pathogens like Vibrio are growing at higher rates, and oysters are becoming contaminated.

Get Our Free Weekly Newsletter

- Sign up for CNN Opinion’s newsletter

- Join us on Twitter and Facebook

There’s also the runoff issue: When you have elevated rainfall levels, what happens to the flow of water into crop areas? And what is that flow bringing along with it? Certainly, agricultural officials working in every state are cognizant of shutting down fields when there is flood water because we know that can lead to contamination issues. But more minor flooding events — we may not be as cognizant of those.

When you have produce growing adjacent to either poultry operations or livestock operations, what happens to all of that manure, and does it contaminate agricultural water supplies? I think water is going to emerge as a huge issue. And one of the reasons the Food Safety Modernization Act is targeting agricultural water is so that we don’t unintentionally introduce pathogens in places we don’t want them.

Maybe the rules that used to apply 20 years ago don’t apply now because of what’s happening to our climate.

CNN: What would you say to people who are concerned about food contamination? How worried should they be, and what advice do you have that might help them stay healthy?

Donnelly: I have a lot of confidence in the food supply. I think we’ve got systems in place that do a good job of making sure that consumers are getting good products. But that said, we should be alert to problems that are out there. Individuals who don’t feel good — people who have cold symptoms, for instance — they think, ”Oh, it’s just a cold or a virus.” Well, it could be something a lot worse than that. So, pay attention to your health.