Editor’s Note: Thomas Balcerski teaches history at Eastern Connecticut State University. He is the author of “Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King” (Oxford University Press). He tweets @tbalcerski. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion at CNN.

More than two weeks after Election Day, President Donald Trump still refuses to concede the race to former Vice President Joe Biden. Some high-ranking former officials from Trump’s own administration (most recently his former chief of staff, John Kelly) have called for a smooth transition. And yet, many Republicans in Congress continue to stand by the President.

In reality, Trump is a lame duck president. Trump’s presidency has been unprecedented in many ways, but in this regard, he is like all his predecessors: His term in office will come to an end, and he will have to depart the White House to begin his next chapter. How Trump chooses to conduct the remaining days of his administration may yet define his presidency and prove a critical moment in American history.

Unfortunately, the country has suffered through some truly terrible transitions. Three such transfers of power come to mind — James Buchanan to Abraham Lincoln during the secession winter of 1860 to 1861; Herbert Hoover to Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the worsening economic crisis of 1932 to 1933; and Bill Clinton to George W. Bush after the bitterly contested election of 2000.

As January 20, 2021, approaches, the need for an effective transition has never been greater. The worsening Covid-19 pandemic demands a strong response from the executive branch, which will require the outgoing president to cooperate with the president-elect for the good of the nation. To avoid further tragedy, Trump and Biden must avoid the mistakes of these truly poor transitions.

Here are three critical lame-duck periods from the nation’s past.

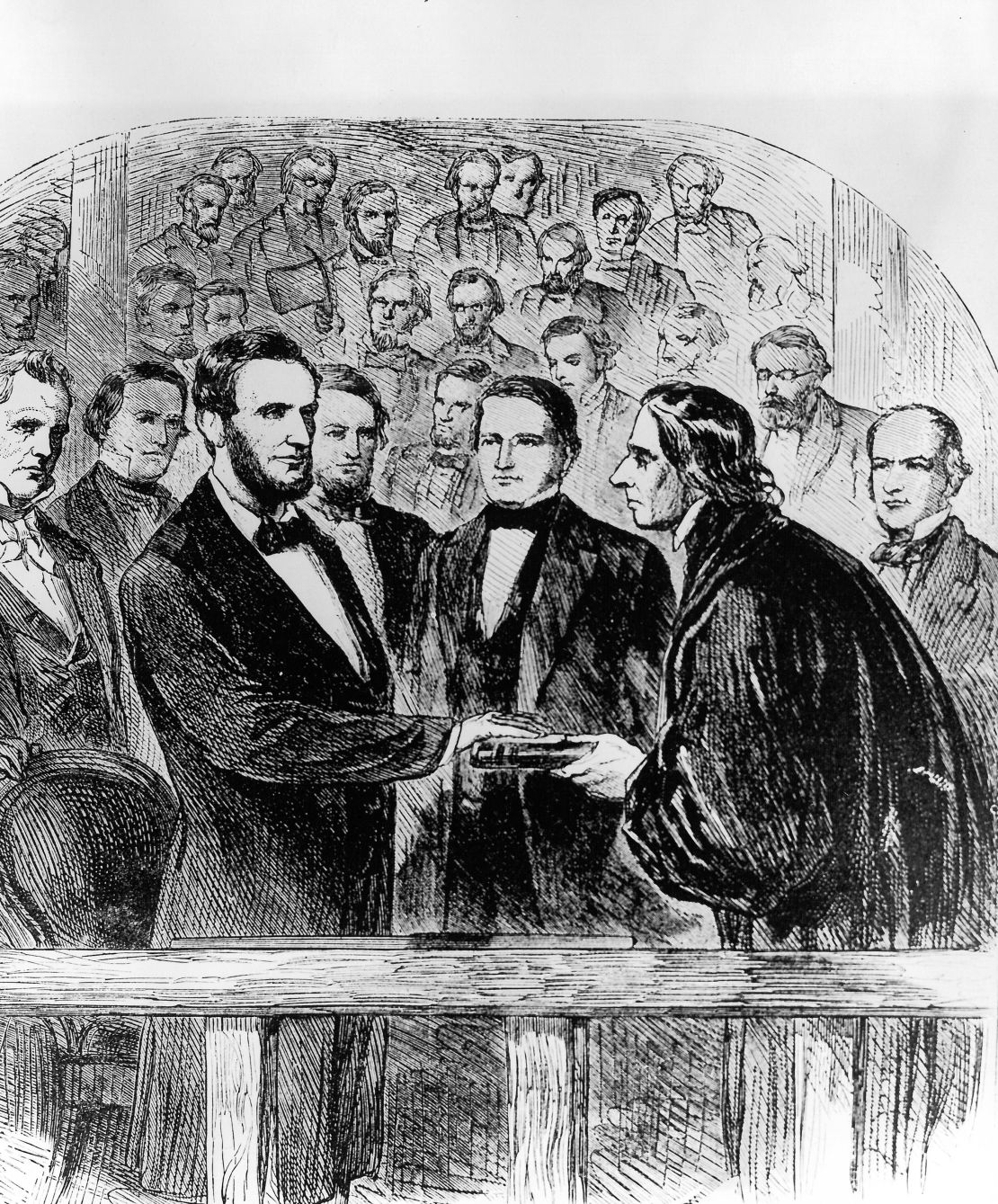

1860-1861: James Buchanan to Abraham Lincoln

The election of 1860 provoked a serious challenge to presidential transition. In November, Lincoln won sufficient votes in the Electoral College to beat three challengers and secure a term as president. One month later, South Carolina gathered a statewide convention and unanimously voted to secede from the Union. Soon thereafter, six more southern states followed suit.

Lame duck President Buchanan poorly managed the developing crisis. He announced himself against southern secession, yet he also believed the government powerless to prevent the action. Instead, Buchanan looked to Congress for a solution. A gathering of “old gentlemen” in Washington, DC, yielded a series of appeasement measures, known as the Crittenden Compromise, which aimed to protect slavery by constitutional provision.

But President-elect Lincoln wisely refused to accept any compromise emanating from the unpopular Buchanan administration. On Inauguration Day, Lincoln called on Buchanan at the White House, and the two men rode together in an open carriage to the Capitol. Despite a conciliatory inaugural address, war erupted when Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumter in April 1861.

The new Republican Congress was furious with Buchanan’s actions during the lame duck period. They took away the franking privilege for ex-presidents (thus requiring them to affix their own postage) – and even declined to pay for Buchanan’s official portrait.

Buchanan defended his actions on the “eve of rebellion” in what historians consider the first presidential memoir, but he failed to rehabilitate his reputation. For his inaction as the Union fell apart around him, he is routinely ranked the worst president in American history.

1932-1933: Herbert Hoover to Franklin D. Roosevelt

By 1932, the Great Depression had plunged the American economy to new lows. Confidence had been lost in the banking system, farmers could find no market for their crops and unemployment reached nearly 25%.

In November, Roosevelt’s promise of a government-sponsored New Deal handily defeated Hoover’s campaign for cooperative voluntarism among private individuals. The day after Election Day, at 9:34 p.m., Hoover begrudgingly conceded by telegram, writing: “In the common purpose of all of us, I shall dedicate myself to every possible helpful effort.”

But, in reality, Hoover did everything in his power to stand in the way of Roosevelt’s New Deal. In effect, Hoover wanted Roosevelt to renounce portions of the New Deal, like his public works programs, before taking office. In turn, Roosevelt refused to collaborate in any way with the outgoing president.

In the meantime, the effects of the Great Depression only worsened. On Inauguration Day, Hoover and Roosevelt shared a tense ride from the White House to the Capitol, with Roosevelt making small talk about the impressive preparations along the parade route.

Mercifully, the extended lame-duck period, designed for an era when Americans traveled by horse or sail, was nearing its end. In 1933, Congress belatedly passed legislation – first proposed by Sen. George Norris of Nebraska in 1923 – that eventually became the 20th Amendment to the US Constitution. Among other things, the “lame duck amendment” moved forward the expiration of an outgoing president’s term from March 4 to January 20 at noon.

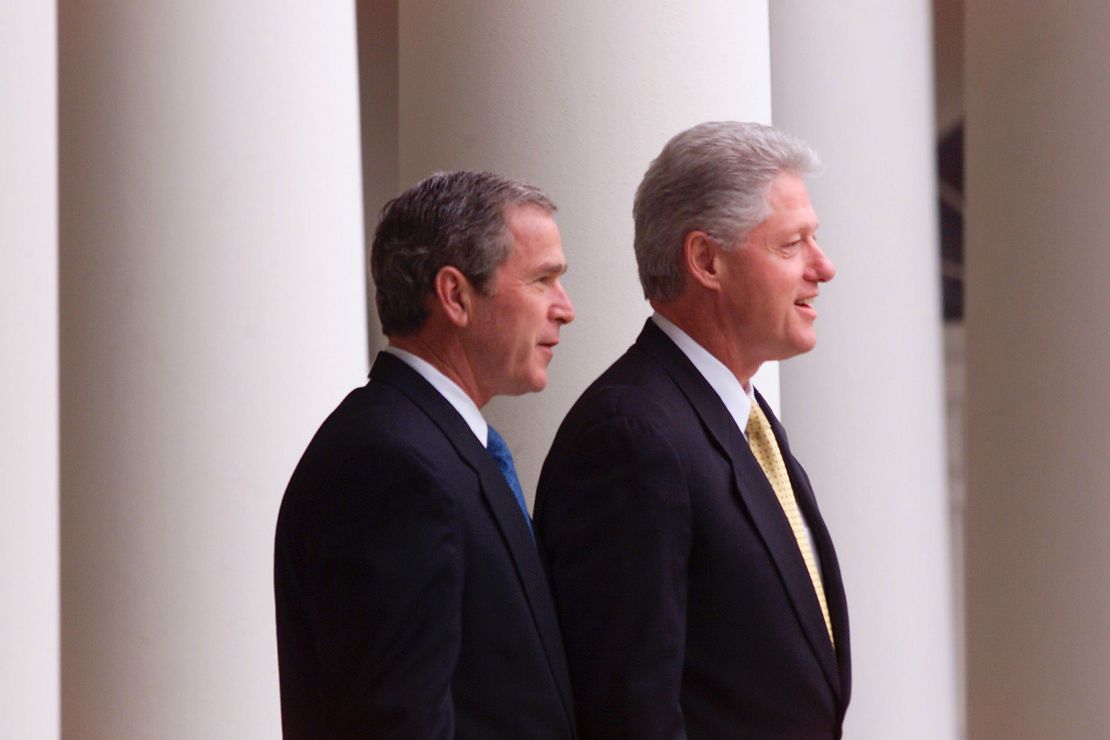

2000-2001: Bill Clinton to George W. Bush

Little did the country know the crisis that would unfold starting on November 7, 2000. In one of the closest races in American history, Vice President Al Gore and Texas Gov. George W. Bush each racked up key wins in the battleground states. Yet no winner could be declared in the crucial state of Florida, despite nearly every major network calling the state earlier in the night for Gore and then reversing the call in Bush’s favor.

Believing that he had lost, Gore had actually telephoned Bush to concede. The vice president was en route to speak before an assembled crowd at the War Memorial in Nashville, when aides frantically rushed to stop him from going on stage. News that Florida was too close to call now convinced Gore to retract his concession and thus began a weekslong legal fight. Finally, after the Supreme Court stopped the Florida recount, Gore conceded on December 13 in a nationally televised address.

As the nation awaited the result, the General Services Administration, the agency tasked with smoothing the transition to the new president, withheld “ascertainment” from both candidates. The decision delayed implementation of the Presidential Transition Act, which provides for office space and equipment as well as funds to support the incoming administration. However, Bush did receive classified briefings (and Gore received them as vice president). Still, in 2004, the 9/11 Commission found that this slow transition “hampered” the new administration’s ability to place key officials in national security roles.

Yet the drama was not over – President Bill Clinton’s administration did not go quietly into the night. Allegations surfaced that personnel ripped phones from the walls, defaced bathrooms, and, perhaps most childishly, removed the letter “W” from keyboards in White House computers (Clinton staffers denied many of the claims). The General Accounting Office issued a report estimating some $15,000 worth of damages.

Get our free weekly newsletter

In response, Bush diligently worked to ensure a professional transition, when the time came to pass power to President-elect Barack Obama. Described as the “gold standard” of presidential transition, Obama himself followed the model in the peaceful transfer of power to Trump.

Of course, Trump may yet concede the election and thus follow a venerable tradition of unifying the country that dates back to 1896. From there, he might follow past precedent and choose to attend his successor’s inauguration.

Yet if past is prologue, the nation should expect a continued crisis and a challenging transition period ahead. As we have too many times before, we must be prepared for a long winter of division between the outgoing and incoming administrations – and for the nation to suffer the consequences.