Story highlights

Testimony focuses on shooting death of MIT officer, 26

Sean Collier killed three days after Boston bombings

Cyclist IDs Tsarnaev, puts him at scene of Collier killing

It was 9:35 on a slow Thursday night in April 2013 and Massachusetts Institute of Technology Police Chief John DiFava was about to call it quits. On his way out, he saw one of his rookie swing-shift officers, Sean Collier, sitting in his cruiser. He stopped to say goodnight.

“I chatted with him for a few minutes. I told him to be safe and I left,” the chief told a crowded courtroom on Wednesday. He estimated the conversation lasted three, maybe four minutes.

“Did you ever see Sean Collier alive again after that?” Assistant U.S. Attorney William Weinreb asked.

“I did not.”

Less than an hour later, Collier lay bleeding in his patrol car after being ambushed and shot in the head. His car door was open, and his foot was lodged between the gas and brake pedals.

DiFava and other officers, assisted by surveillance videos, 911 callers and a lone bicyclist who happened to be passing by, recounted Collier’s last moments in the death penalty trial of admitted Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.

The bicyclist, MIT mathematics Ph.D. candidate Nathan Harman, pointed to Tsarnaev in court and identified him as the man with “a big nose,” who he saw leaning into Collier’s squad car. He said Tsarnaev appeared to be alone.

Tsarnaev, who was 19 at the time, does not dispute that he was present when Collier was killed on the evening of April 18, nor does he deny that he participated in the bombings three days earlier that killed three people and hurt more than 240 others.

Prosecutors say Tsarnaev and his older brother, Tamerlan Tsarnaev, killed Collier because they wanted his gun. But their efforts to take it were thwarted by a safety holster.

The FBI had released photos of the pair five hours earlier, and they were on the run. But Tamerlan, 26, would not survive the night. He was killed in a chase and gunbattle with police that began with reports of an “officer down” at MIT.

The MIT police, who are designated as special officers by the Massachusetts State Police, patrol the sprawling campus in Cambridge. Collier’s beat was the area of North Quad near Main and Vassar streets. He had been handling a routine call about a citizen who was upset his car had been towed.

A young man called 911 about 10:20 p.m. and reported hearing loud noises outside his window.

“They don’t sound exactly like gunshots,” the caller told dispatcher David Sacco. He wasn’t sure what they were. Maybe somebody banging on trash cans.

Sacco tried to summon Collier on his police radio. No response. He sent an emergency alert. Nothing. He tried texting him. Still no response.

“It became an amount of time that wasn’t comfortable,” he said.

Sgt. Clarence Henniger had returned to the station at the end of his shift, and had just passed Collier on the way in. He saw nothing out of the ordinary. But when he heard dispatch couldn’t raise Collier, he went back out to check on him. His car was in the same spot.

“I parked about 8-10 meters away from Officer Collier’s car,” Henniger said. “When I arrived at the cruiser I looked inside and that’s when I observed a wound to the head, to the temple. I observed a wound to the neck and I observed a wound to his hand.”

Prosecutor Weinreb asked: “Was there blood?”

“Yes sir,” the witness responded.

“Where?”

“All over the car and his body.”

Jurors heard Henniger’s frantic call over the police radio:

“Officer down! Officer down! Get me help! Officer down.” He called for an ambulance, shouting, “Get on it!!!”

He and another officer pulled Collier out of the squad car to attempt to revive him.

“The amount of blood on his body made it difficult to get a grip on him,” Henniger said. The other officer urged Collier to “Hang in there, just hang in there,” and asked “Who did this to you?”

Collier did not respond.

Cambridge police officer Brendan O’Hearn joined them, and took over applying chest compressions.

“His face and neck were covered with blood. There was some type of wound to his head,” O’Hearn said. Collier was gurgling and blood was coming from his mouth

“There was blood everywhere,” O’Hearn added.

Weinreb asked, “Did it transfer to you?”

“All over me.”

Collier became the fourth victim of the Tsarnaev brothers.

Campus surveillance cameras captured the encounter between Collier and his killer. The footage was shot from a distance and at times, it is difficult to determine whether the cameras captured one person and a shadow or a pair walking closely together.

The video shows Collier’s patrol car idling near the front of the Koch Institute building, and a person or two people rounding the corner and walking towards it. The brake lights flash on, then off, and then off again. Two people can be seen running back around the corner.

Off to the side, somebody on a bicycle rides by without stopping.

Harman, the grad student on the bicycle, often used the word “they” in his testimony at first, but said he saw just one person as he pedaled past.

“When I went by, the front door was open, the driver’s side door,” he said. “There was someone leaning into the driver’s side door.” He said the person – although he used the word “they” – was bent at the waist and leaning into the patrol car.

“They stood up, startled, as I rode my bike by them,” he added.

Later in his testimony, he began referring to “they” as “he.”

“I only saw one person,” he said. “He sort of snapped up, stood up, and turned around. He looked startled. We made eye contact.”

Asked to describe who he saw, Harman added, “I remember thinking he had a big nose.”

He looked across the courtroom at Tsarnaev, pointed, and said, “He’s right there.”

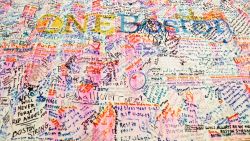

The prosecution’s case has brought one dramatic day of testimony after another in the federal courthouse overlooking Boston Harbor. On Tuesday, prosecutors displayed photos of what they called Tsarnaev’s “manifesto,” scrawled in pencil on the sides of a dry-docked pleasure boat where he sought refuge April 19.

Blood streaks and bullet holes punctuated his words, which he does not deny writing. The only issue in dispute is whether it is a confession or something else.