Story highlights

ISIS loses control of Palmyra, including ancient cultural treasures

While some artifacts were destroyed, others remain untouched or can be saved

Russian President Vladimir Putin pledges support for conservation and restoration of ancient treasures

Syrian troops rolled into the occupied city of Palmyra late last week, capturing the ancient Palmyra Castle as they marched toward the ISIS fighters commanding the ancient city, state-run media said.

And as the UNESCO world heritage site comes once again under the control of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s forces, eyes turn to the vandalism wrought on its ancient treasures by the brutal, unbending jihadist group, which sees ancient artifacts as un-Islamic and ripe for destruction.

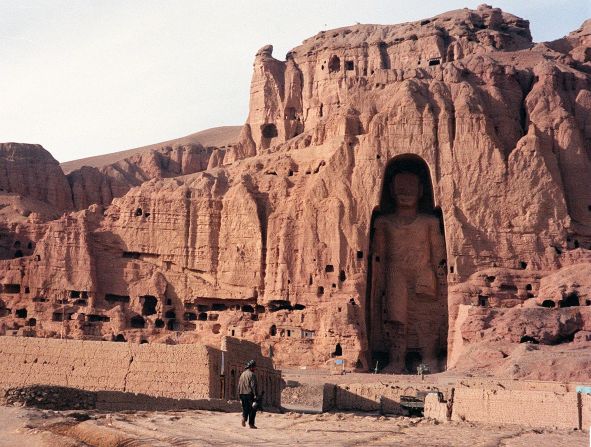

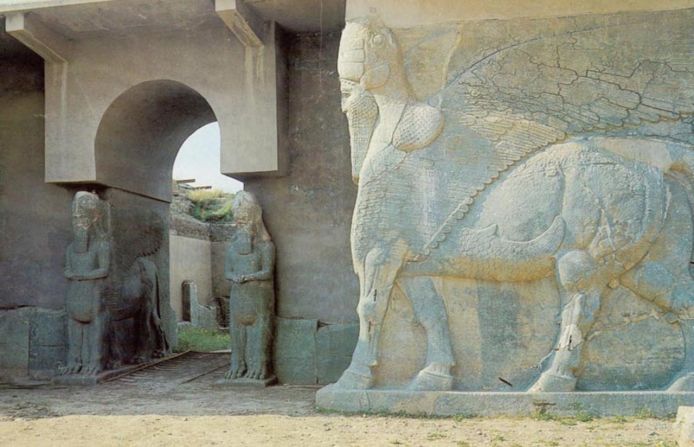

Precious monuments lost in Middle East

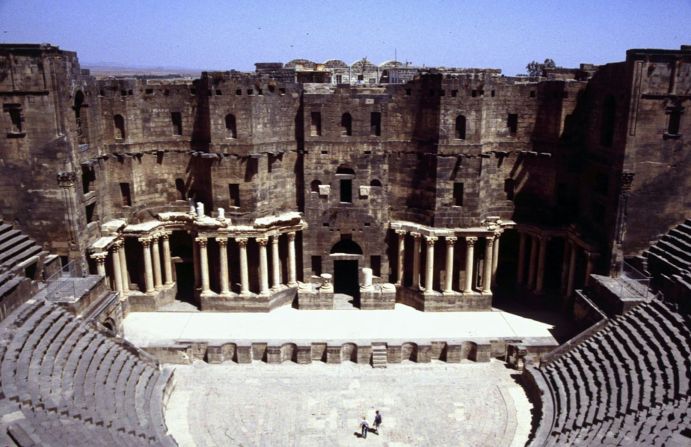

UNESCO says it plans to evaluate the extent of the damage soon. But images taken in the aftermath of Syrian troops’ regaining of the city show many of the structures – which date from the first and second centuries and marry Greco-Roman techniques with local traditions and Persian influences – remain in place, bolstering hopes that ISIS didn’t completely raze the ancient site.

“I am the happiest person in the world,” Syria’s antiquities chief Maamoun Abdulkarim told Christiane Amanpour following the recapture of the ancient city from ISIS.

He added that the destroyed temples will be rebuilt as “a message of anti-terror.”

Photos of the National Museum in Palmyra, obtained by the Syrian Directorate-General of Antiquities and Monuments, show statues with faces chipped off – in keeping with strict Sharia interpretations of the depiction of human forms – and statues smashed on the floor. Authorities evacuated what they could from the museum, but larger items and those fixed to walls had to be left to the mercies of the invading militants.

However, the directorate was positive that the condition of the artifacts meant that they could be restored and their “historic value” returned, according to a translation of an article on the department’s website.

Likewise, photos of a Roman-era amphitheater, the Temple of Bel and the Colonnade obtained by the Syrian government appear to show the ancient ruins in good condition.

International support, reconstruction

Irina Bokova, director-general of UNESCO, spoke to Russian President Vladimir Putin, a key Assad ally whose airstrikes facilitated the Syrians’ retaking of the city. Putin promised material support for preservation and reconstruction work in Palmyra, according to a press release on the UNESCO website.

The article also says that Bokova spoke to Maamoun Abdulkarim, director-general of Syrian antiquities and museums, reiterating the U.N. body’s “full support” for the restoration of the ancient treasures, underscoring “the critical role of cultural heritage for resilience, national unity, and peace.”

The directorate posted a moving tribute on its website to Khaled al-As’ad, a curator who was beheaded by ISIS last year.

“We promise to restore the city as it used to be, in a cultural and intellectual message opposite to the destruction and terror, so the city will again represent the tolerance and multicultural richness that Palmyra has had through history, the things that the militants of ISIS hate the most,” the statement says.

Destruction of history

ISIS took over the central Syrian city last May, expanding its conquests in the region and continuing to show its contempt for the people and their history.

By June, the Islamic extremist group began destroying historical sites. The Syrian government said ISIS destroyed two Muslim holy sites: a 500-year-old shrine and a tomb where a descendant of the Prophet Mohammed’s cousin was reportedly buried.

Two months later ISIS destroyed more antiquities, including the 1,800-year-old Arch of Triumph that framed the approach to the city and the nearly 2,000-year-old Temple of Baalshamin.

UNESCO called the temple’s destruction a war crime.

Palmyra, in the Homs countryside northeast of Damascus, was a caravan oasis when Romans overtook it in the mid-first century. In the centuries that followed, the area “stood at the crossroads of several civilizations” with its art and architecture mixing Greek, Roman and Persian influences, according to UNESCO.