Editor’s Note: CNN Travel’s series often carries sponsorship originating from the countries and regions we profile. However, CNN retains full editorial control over all of its reports. Read the policy.

With the exception of the march across the Philippine island of Luzon, the battle of Okinawa was the only major American land campaign in the Pacific during World War II.

Launched on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945, it was fought in villages and towns – the island’s wartime population was roughly 500,000 – as well as across the island’s forbidding mountain ridges and valleys. For the American attackers, the battle was an operation of logistics as well as military strategy.

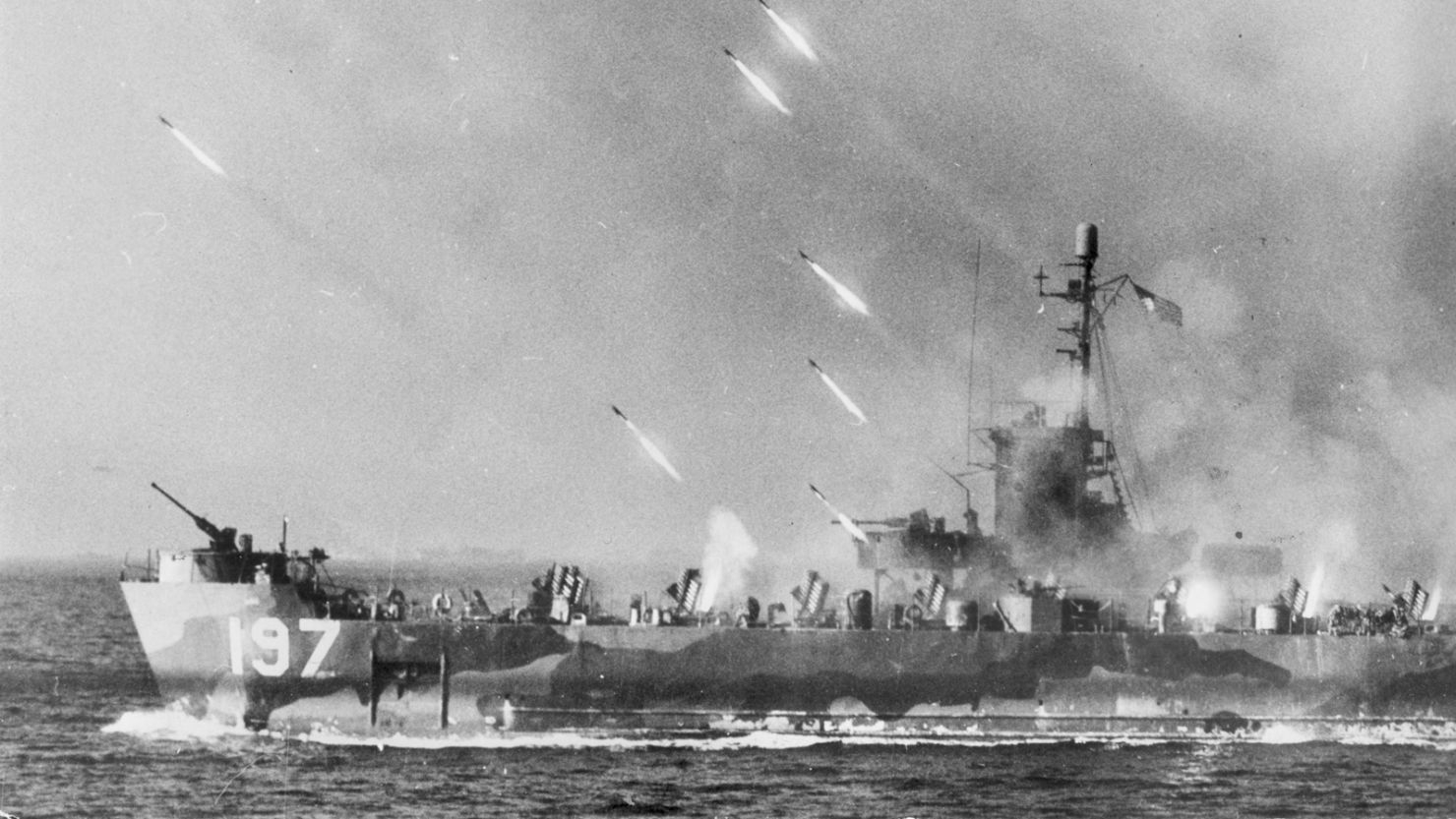

“Never before … had there been an invasion armada the equal of the 1,600 seagoing ships carrying 545,000 American GIs and Marines that streamed across the Pacific,” wrote historian Robert Leckie in Delivered From Evil: The Saga of World War II. “In firepower, troops, and tonnage it eclipsed even the more famous D day in Normandy.”

The American armed force that Leckie called a “monster of consumption” had to be supplied 7,500 miles from the country’s western shore. No amphibious operation in military history comes close to matching it on a scale of distance and enormity.

On land, Okinawa quickly devolved into a sadistic killing ground. Absorbing the highest casualties they’d ever endured in a single battle, U.S. forces nevertheless closed on strongholds around the island held by depleted but supernaturally tenacious and courageous Japanese forces, both military and civilian.

Exhausted from years of war and bitter privation, the Japanese withdrew to a final defensive line along the southern coast.

With American troops barely 100 feet away, army commanders Lt. Gen. Mitsuri Ushijima and Lt. Gen. Isamu Cho donned dress uniforms, sat on a white sheet on a ledge overlooking the sea and committed the ritual suicides befitting their samurai heritage.

On June 22, the battle was officially declared over.

An estimated 100,000 Japanese soldiers were killed along with 80,000-100,000 civilians. American casualties amounted to 12,520 killed, including 5,000 at sea, the worst losses suffered in any campaign in the history of the U.S. Navy, and 37,000 wounded.

All told, Okinawa was the bloodiest operation of the Pacific War.

The island quickly became a massive American base, the intended staging ground for the coming invasion of the Japan home islands, just 600 kilometers (375 miles) away. The invasion would be rendered needless by the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki just six weeks after the Battle of Okinawa ended.

The American military has never left Okinawa. Indeed, today, most international news coverage of the island deals with U.S.-Okinawa tensions, sensitive military aircraft activity and misbehaving service members.

Given this tense history, one might expect to encounter a more austere landscape and surly people, vehemently opposed to all things foreign, especially American.

Yet this isn’t the case.

Okinawans are extremely genuine and accepting people. “Mensore” (welcome) is the first word tourists see when arriving at Okinawa’s Naha airport – it’s displayed in banners across shops and often offered with a warm smile.

Why then, in light of the long-running foreign military presence, are Okinawans such a happy people?

For many, the answer is rooted in lessons learned from a disastrous war.

Across the islands, especially the main island in areas easily accessible from Naha, memorials and battle sites have been preserved, commemorating the tragic battle while confirming Okinawans’ deep respect for the value of peace.

Anthony Bourdain: Okinawa more laid-back than rest of Japan

Remnants of war

I recently joined a good friend, Kayla, on a jungle trek in search of remnants of the war. Kayla is a military spouse who moved to Okinawa when her husband was assigned here.

A student of American history, Kayla saw an opportunity to study the Battle of Okinawa in a personal way.

“It’s our backyard,” she says, adding that her research has led to a very different view of her new home.

“Everything is built up now, but I try to see it without all the buildings and structures, which makes [the battle] very real.”

Travel to Japan’s tropical southern end

Japanese observation post, Nakagusuku

Through a roughly overgrown path and up a steep hill, Kayla leads me to an amazingly well preserved Japanese observation post in Nakagusuku Village.

Perched atop the hill is 161.8 Kouchi Jinchi, or “High-ground Position,” named for its peak at 161.8 meters above sea level.

The post is constructed of rebar-enforced cement and stone, with four openings overlooking a large portion of central Okinawa, affording a clear view out to sea.

Complete with trench defenses and an underground cave, the Japanese army built the observation post as part its extensive defensive network.

Looking out, the impact of the war feels shockingly tangible. Perhaps most surprising, this particular location was recorded by the ancient Ryukyu Royal Government as a sacred place of prayer, Kishimako-no-taki, some 200 years before the war.

GETTING THERE: Located in Ginowan/Nakagusuku, 161.8 Kouchi Jinchi is part of a historic trail used by the Ryukyu Kingdom that stretched from the Southern Shuri Castle to Northern Nakagusuku Castle. Parts of the trail are still walkable, though about 50 percent is currently under renovation. The observation post is in the middle of this trail, accessible by starting at the trail opening from Nakagusuku Castle, or via highway 29, closest landmark is the Okinawa Fire Academy.

Japanese Navy Underground Headquarters

Located in Tomishiro City, the Japanese Navy Underground Headquarters is where Rear Admiral Minoru Ota, his officers and men, staged a last stand against rapidly advancing enemy troops.

Designed as a series of semi-circular tunnels 450 meters (1,475 feet) in length that could sustain 4,000 people, the headquarters was dug out with shovels and picks by soldiers and civilians, nearly all by then living on starvation rations.

Touring these tunnels is a profoundly somber experience.

With 300 meters open to the public, visitors can view portions of the tunnel complex and hallways housing troop berthing, the commanding officer’s quarters and a shrapnel-riddled staff room where Ota and his officers committed suicide hours before U.S. forces gained access.

GETTING THERE: Japanese Navy Underground Headquarters, 236 Aza Tomishiro, Tomishiro-city, Okinawa; Open daily, 8:30 a.m.-5 p.m.; +81 98 859 6123

Himeyuri Peace Museum

The Himeyuri Peace Museum is dedicated to preserving the memory of 240 students and teachers from the Female Division of the Okinawa Normal School and Okinawa First Girls’ High School.

On March 23, 1945, these students and teachers were inducted into units of the Okinawa Army Field Hospital serving the Japanese Imperial Army.

Based in a cave network, they worked in wretched conditions, living in miserable and dirty wards, experiencing the horrifying reality of wounded and dying soldiers.

Assigned to work as nurse assistants, they cared for the injured around the clock, braved bombardment and gunfire carrying water and food to patients and hospital staff and burying the dead. In its 1989 dedication address, the Himeyuri Alumnae Foundation described the fate of the students once Japanese defense of Okinawa became untenable.

Suddenly dismissed on June 18, 1945, “the students had nowhere to go under the U.S. siege, some killed in the battle raging around them, while others killed themselves with shells or hand grenades.”

The loss was overwhelming. Of the 240 students, 227 perished.

In front of the Himeyuri Peace Museum is the cave opening of the former field hospital’s main facility. Visitors are encouraged to observe a moment of silence or prayer for the students. Many offer flowers in dedication.

GETTING THERE: Himeyuri Peace Museum, 671-1 Aza-Ihara, Itoman, 901-0344; Open daily, 9 a.m.-5 p.m., Okinawa;+81 98 997 2100

Ernie Pyle Memorial, Ie Shima

Those visiting Ie Shima, a small island just west of Okinawa, will find a quiet, sparsely populated community of farmers and craftsmen.

On April 16, 1945, Ie Shima saw some of the worst fighting, with Japanese forces augmented by the island’s organized resident defense force. About 6,000 defenders lost their lives that day, including Ie Shima’s volunteer men and women.

Known for his intimate portrayals of frontline conditions and stories of the hardships faced by American troops, American war correspondent Ernie Pyle was killed in combat on Ie Shima.

Located just minutes from Ie Shima’s main port, the Ernie Pyle Memorial marks his initial burial ground. (Pyle’s remains were reinterred to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu.)

The Okinawa American Legion and a small detachment of Marines stationed on the island hold an annual memorial service in April.

Ie Shima Village Office; +81 98 049 2001

1,000 Man Cave, Ie Shima

Many of Ie Shima’s residents had no way to escape during the fighting, seeking shelter and protection from American bombardment in a cave located at water’s edge, on the southern end of island.

Known as 1,000 Man Cave, local residents hid in its four large chambers during the three months of fighting.

I visited the cave with a U.S. Marine stationed at the island’s training facility, one of only 11 American service members living on Ie Shima.

Even on the sunniest of days, the internal chambers were dim and dreary, the sandy floor and coral rock walls cool and wet from the ebbing tide.

“I love the ocean,” the marine said, perched upon a rock at one of the cave’s openings to the sea. “It’s hard to imagine the war, though, how loud and scary it must have been.”

Indeed, we were surrounded by quiet, interrupted only by the rush and lapping of calm waves.

The din of war and destruction, far from this tranquility and peace, was absolutely unimaginable.

Ie Shima Village Office; +81 98 049 2001

Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum

The most comprehensive memorial to the Battle of Okinawa is the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum, located Itoman City.

The museum houses numerous exhibits recounting ancient Ryukyuan history, Okinawa’s annexation as a prefecture of Japan, the rapid modernization and build-up to war, conditions of battleground Okinawa and continued military presence.

With a research library, dramatic recreations, original artifacts and survivor testimonies, the museum offers visitors a view of Okinawa’s war-stricken past, while offering a vision of hope for the future.

The view from the museum’s eternal fire monument stretches vast and blue, an unrestrained look across Okinawa’s gorgeous waters.

Museum officials assert that the horrors faced during the war form the core of what’s called the “Okinawan Heart,” a “resilient yet strong attitude to life that the Okinawan people developed, respecting personal dignity, rejecting war and truly cherishing culture.”

Getting there: Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum, 614-1 Aza-Mabuni, Itoman City, 901-0333, Okinawa; Open daily, 9 a.m.–5 p.m.; +81 098 997 3844

For more information on Okinawa war history tours, contact the Battle of Okinawa Historical Society via their Facebook page.

Christopher Dong is a freelance-writer based in Okinawa.