Editor’s Note: This version of a story published on May 23 has been updated to include Shinseki’s resignation

Story highlights

NEW: Eric Shinseki resigns over VA scandal, Obama accepts it with regrets

Pressure mounted for Shinseki to step down over VA wait list, cover-up allegations

Shinseki, a man of few words, was in the spotlight before over the Iraq war

Those who know Eric Shinseki chuckled when their laconic friend began his Army retirement speech in 2003 with this: “‘My name is Shinseki, and I am a soldier.”

It was pure Shinseki, longtime friend Rollie Stichweh thought.

Shinseki, ending his Army career that day as chief of staff, had always been a man of few words.

“Ric is quiet, low-key,” said Stichweh, who graduated from West Point with Shinseki in 1965. “He’s never been an extrovert. He hates being the center of attention.”

More than a decade later, Shinseki had very much become the center of attention with his leadership of the Department of Veterans Affairs under intense fire over allegations that some VA health care facilities covered up long patient wait times for veterans.

Saying he did not want to be a distraction going forward, the former Army general submitted his resignation to President Barack Obama on Friday. The President said he accepted it, but regretted doing so.

“Ric’s commitment to our veterans is unquestioned. His service to our country is exemplary. I am grateful for his service, as are many veterans across the country,” Obama said.

Shinseki left his White House meeting, quietly, saying nothing to the press.

Earlier in the day, he apologized for the scandal that prompted more than 100 members of the House and Senate to call for his resignation and has Justice Department prosecutors sniffing around.

CNN has reported exclusively about problems with veterans trying to access health care.

Doctor says Phoenix VA ignored mandate

The VA has weathered other scandals since its creation in 1930. But veterans say this one puts the department at a crossroads.

With Shinseki out, the question now is whether the newest revelations will lead to a substantial housecleaning at the sprawling bureaucracy charged with caring for millions of veterans, including injured warriors, followed by reforms?

Or, will a legacy of serious problems at the agency and failed efforts to reverse it continue beyond this administration as a new generation of veterans emerging from 12 years of nonstop war swell demands for care.

“This isn’t about one person,” House Speaker John Boehner has said. “It is about the entire system underneath him.”

‘Anguished’

But as every military member knows, the buck stops at the top.

Obama nominated Shinseki before taking office, saying the decorated Vietnam veteran and former Army head was a man who “always stood on principle.” He was easily confirmed in January 2009.

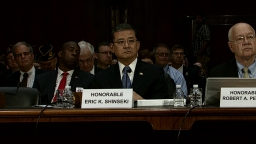

At the confirmation hearing, lawmakers had mostly praise for Shinseki, who was known in Washington circles for his valor and long commitment to service in the Army.

Shinseki promised then he would come up with a “concise strategy for pursuing a transformed Department of Veterans Affairs,” vowing to make the VA a “people-centric, results-driven, forward-looking” institution.

Obama has promised accountability.

“We are going to fix whatever is wrong,” the President said.

Shinseki, who supporters say did make some strides during his leadership of the VA, told the Senate earlier this month it was too soon to cast blame over the latest revelations.

He also displayed a rare moment of emotion.

“Any allegation, any adverse incident like this makes me mad as hell,” he said.

He launched an internal review and began the process of firing some top people. But details of an independent report released in recent days by the VA inspector general’s office outlining systemic problems spelled the end of his tenure.

Stichweh told CNN that he and Shinseki have talked about how the controversy has affected him, but Stichweh felt it would be a betrayal of Shinseki’s trust – and the privacy the general cherishes – to share any of that with CNN.

“He is anguished over this, I can tell you that. He feels it,” said Stichweh, a retired business consultant who lives in Connecticut. “There is nothing he cares about more than veterans.”

Words fail him

Words are not enough for veterans groups. There must be systemic reform at the VA that goes beyond a single person, they said. But it has to be coordinated by one person, and they came to doubt whether it should be Shinseki.

He just wasn’t candid enough, says Paul Rieckhoff, an Iraq war veteran and the executive director of the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America.

The organization that serves 2.8 million Iraq and Afghanistan veterans sought for years to get him to talk frankly with them about a variety of veterans’ needs, Rieckhoff said.

“There’s no doubt he’s let the relationship with veterans fall apart over the years,” Rieckhoff said, pointing to the VA’s disability backlog problem that CNN and other outlets have covered.

The Washington Post has reported that almost half of Afghanistan and Iraq veterans are filing for disability benefits when they leave the military. The VA is saddled, the Post reported, with a backlog of 300,000 cases, some of which are taking months to process, others more than a year.

Rieckhoff, 39, acknowledged Shinseki’s admirable military career, but said that spoke to the past.

“We are living too much in the past,” he said.

Shinseki also came under pressure from the American Legion’s national commander, Dan Dellinger, who called for his resignation.

The group hadn’t taken such a step in 30 years, he said, but VA leaders were failing badly to respond to questions.

“Senior VA leaders have isolated themselves from the media and, more importantly, from answering to their shareholders, America’s veterans,” Dellinger wrote in an online note to members.

From the jungle to the capital

Two moments in Shinseki’s public life have come to define him.

One took place in the jungles of Vietnam.

Another played out in the battlefield of Washington, just before the Iraq War.

Shinseki was born in Hawaii to Japanese-American parents less than a year after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941.

Despite hostility toward Japanese-Americans, three of Shinseki’s uncles enlisted in the Army and served in Europe in the 100th Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team, both made up of U.S.-born Japanese, according to Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Stichweh recalls meeting Shinseki and wanting immediately to ask why he would want to serve in the military, given the time when Shinseki was born and raised, his family’s background and the fact that some Americans were still, at that time, not particularly warm to people of Japanese descent.

“I asked ‘Gee, why would you want to be an officer?’ And he told me about his family and what that history meant to him,” Stichweh said.

A Boy Scout, Shinseki was raised to understand the importance of order and discipline. He also was an early achiever. He was the student body president at Kauai High School, according to U.S. News & World Report.

He married his high school sweetheart, Patricia. They have two children.

After graduating from the U.S. Military Academy in 1965, Shinseki and Stichweh served in Vietnam. Stichweh left the service after fulfilling his mandated term because he disagreed with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s war strategy.

Shinseki did two combat tours. In 1970, during a fierce gunbattle, he stepped on a landmine and blew off half of his right foot.

Even after that harrowing experience, he lobbied to remain in the Army.

“Ric persuaded the powers that be to let him stay,” Stichweh said. “He nearly died, but he wanted to keep serving.”

Shinseki was awarded a Purple Heart and other honors for his valor.

He returned to active duty in 1971.

Read Shinseki’s official VA bio

The general and Iraq

While working his way up the Army career ladder, Shinseki received a master’s degree in English at Duke University and went back to West Point to teach.

He took important posts at the Pentagon. In 1991, he was promoted to brigadier general, became the commanding general of the 1st Cavalry Division in 1994, and then was named commander in chief of U.S. Army forces in Europe.

Shinseki led NATO land forces in central Europe and commanded a NATO peacekeeping mission in Bosnia-Herzegovina after that conflict.

In the summer of 1999, under President Bill Clinton, Shinseki became Army chief of staff.

The lessons he learned in Bosnia informed the second-most significant – or at least publicly talked about – chapter in Shinseki’s career.

In 2003, a month before the United States invaded Iraq, he testified before Congress it would take “something on the order of several hundred thousand soldiers” to secure the country, far more than what the George W. Bush administration said would be necessary.

Days after Shinseki’s testimony, then-Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld discounted that figure, and his deputy, Paul Wolfowitz, told lawmakers that Shinseki’s estimation was “wildly off the mark.”

Nicolaus Mills, an American history professor at Sarah Lawrence College, said Shinseki was merely using a formula developed by the nonpartisan think tank RAND Corp. The formula was applied during an international peacekeeping mission in Bosnia during the 1990s, Mills said, saying it required one soldier for every 50 civilians to keep the peace after a war.

“He was simply doing the math for Iraq, and we know he turned out to be right,” the professor said.

March 2003 saw a ground invasion force of 145,000 troops, Mills wrote on CNN in March 2013, 10 years after the start of the war.

A month after the invasion, “mobs began looting government buildings and hospitals,” and “there were not enough American soldiers to stop them,” Mills wrote.

A “surge” of troops had to be sent to Iraq during the war to tamp down on insurgents who were attacking U.S. troops and allies. In January 2007, Bush addressed the nation saying, “It is clear that we need to change our strategy in Iraq.”

The United States completed its withdrawal of military personnel in 2011.

When Shinseki retired in June 2003, he was the highest-ranking Asian-American service member.

Former White House adviser and senior CNN political analyst David Gergen said recently that the idea of Shinseki as a person who spoke truth to power has persisted in Washington for years.

Gergen said Shinseki may have gotten the VA post in part because the Obama administration wanted to show he, rather than others, was right about Iraq.

Gergen also stressed it was his recollection that soldiers revered Shinseki, mostly for his valor in Vietnam.

“But I’m not sure there was anything particularly distinguishing about him (to) lead a bureaucracy” the size of the VA, Gergen said.

In 2006, Newsweek asked Shinseki, then in retirement in Hawaii, how he felt about the criticism that he should have pushed harder for more troops at the launch of the Iraq War.

“Probably that’s fair,” he told the magazine. “Not my style.”