Story highlights

Former U.S. Marine Amir Hekmati has been imprisoned in Iran for more than two years

He was visiting family in Iran when he was arrested in August 2011

He wrote a letter to John Kerry saying his confession of being a CIA spy was forced

His family is appealing to Iran's new president, who's attending U.N. General Assembly

The family of former U.S. Marine Amir Hekmati has a message for Iran’s new president: Their American son is not a spy, has never been one, and he should be released immediately from prison in Iran.

“I just ask – I just want the president to consider us as an Iranian family, and that my husband is sick, and me as a mother I’ve suffered a lot, more than two years,” said Behnaz Hekmati, Amir’s mother, speaking in halting English.

The family made a plea in an exclusive interview to CNN on the eve of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s first visit to the United States, where he will attend the U.N. General Assembly.

Amir Hekmati’s father, Ali, is ailing with brain cancer, and the family is imploring the Iranian government to release their son before time runs out for the elder Hekmati.

“Please just let Amir come home,” said Behnaz Hekmati. “Amir didn’t do any crime, he didn’t do anything. Just let him to come home and make his family happy again.”

This month, Amir Hekmati, 30, wrote a letter to U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry saying a confession he made to the spying charges leveled by Iran were “false” and “based solely on confessions obtained by force, threats, miserable prison conditions, and prolonged periods of solitary confinement.”

Hekmati’s family said he had gone to Iran to visit his grandmother when he was arrested in August 2011, accused by Iran’s Intelligence Ministry of working as a CIA agent.

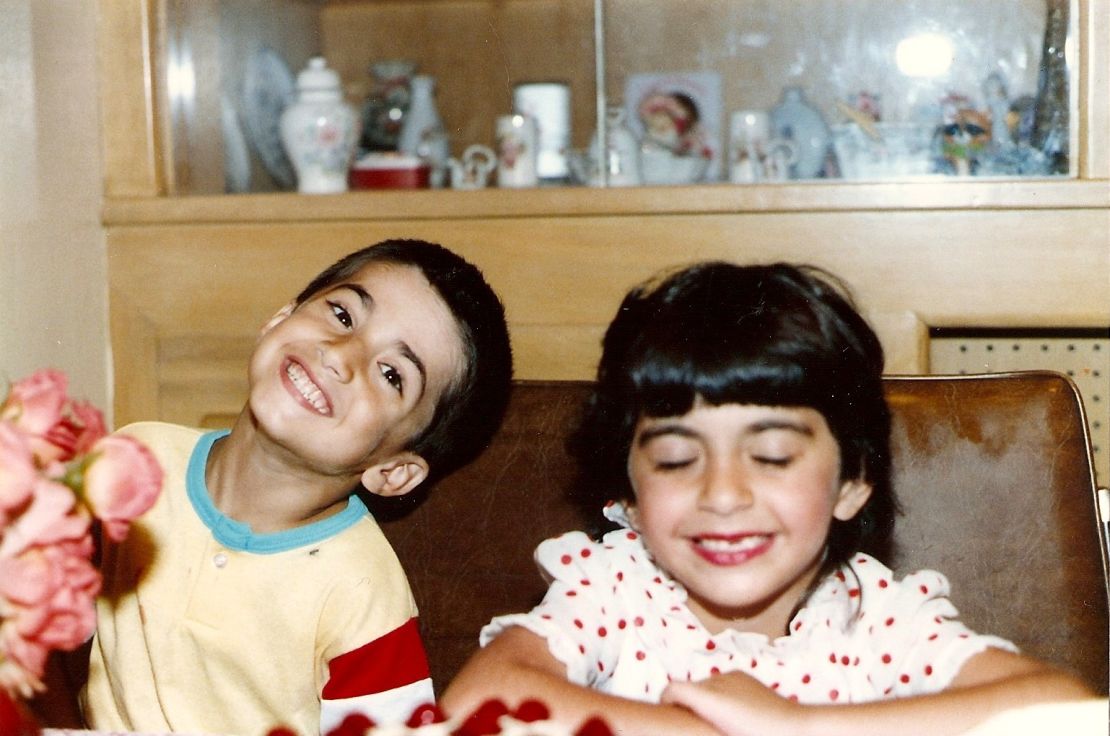

Born in Flagstaff, Arizona, then raised in Flint, Michigan, Hekmati graduated from high school and joined the U.S. Marines, where he served four years, becoming a rifleman and also serving in Iraq.

His parents came to the United States in 1979 as the Islamic revolution spread across Iran.

Two years ago Hekmati surprised his parents by telling them he wanted to visit Iran for the first time, to meet relatives he had never seen – including his ailing grandmother – and find his roots.

“We know there is a risk involved,” Behnaz Hekmati said. “We were always cautioning. And me, as a mother, because I know, I grew up in that country, I always cautioned about, you know, if something happened. But my kids, they said, ‘Mom, my friend, they went, they came back, you know. And nothing’s gonna happen.’ And they never believe me, you know … that it’s very dangerous.”

In August 2011, Amir Hekmati called his mother from Iran to say he was having the time of his life and he would be coming home soon. He told them he would leave two days after a final farewell party his Iranian relatives were having on August 29.

That party came and went; Hekmati never showed up.

For three months, no one in his family knew anything about Hekmati’s whereabouts. Then one day in December 2011, Iranian state television aired Hekmati’s purported confession he was a CIA spy, and announced that he was imprisoned.

The suspect was “tasked with carrying out a complex intelligence operation and infiltrating the Iranian intelligence apparatus,” Iran’s Press TV reported at the time.

The family described being in total shock.

“That day we saw his face. And he was confessing … he’s a CIA spy, and I said, ‘Wow,’ ” his mother said.

Behnaz Hekmati has said all along that her son’s confession was fabricated and forced by his Iranian captors, a position the U.S. State Department supports.

“They had three months to make this story,” his mother said. “They knew from beginning this is a good catch, you know. … He’s a Marine.”

She said she believes that’s why the family was not initially allowed to talk to her son.

“That’s why they didn’t want us to talk to him. Because he’s going to tell us the truth, what happened,” Behnaz Hekmati said. “And they just come up with this story. And an attorney told us same thing. He said, ‘He didn’t do anything.’ “

Asked why it happened to his son, Ali Hekmati offered some thought.

“Naturally, we have some speculations that someone got jealous of him and didn’t like the idea that he lives in America, and they are living over there in Iran,” his father said. “(That person) probably came up with some lies about him, called him a CIA spy, (because) that was his original charge.”

The initial charge and detention has stretched to a two-year ordeal. Weeks after his on-air confession broadcast on Iranian television, Amir Hekmati was tried in an Iranian court and sentenced to death. Months later, Iran’s Supreme Court overturned his death sentence and ordered a retrial. During his imprisonment, Hekmati spent 16 months in solitary confinement and went on a monthlong hunger strike.

The Hekmati family has tried to bring public attention to Amir’s plight, hoping to secure his release. Letter after letter, plea after plea, Amir’s sister Sarah has struggled to get political support to intervene.

Now that Iran has elected a more moderate president, Hassan Rouhani, in place of firebrand Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the family may have a better chance for his release.

“We just hope that we are reaching the ears – especially now with this new transition in government in Iran – the ears of the right people,” Sarah Hekmati said.

The State Department has said Amir Hekmati’s imprisonment follows a pattern by the Iranian regime, which it says “has a history of falsely accusing people of being spies, of eliciting forced confessions, and of holding innocent foreigners for political reason.”

Hekmati is the latest in a series of Americans – most of them Iranian-Americans – to face arrest in the country in recent years:

• In 2007, Iran arrested several Iranian-Americans – including Kian Tajbakhsh, Ali Shakeri and Haleh Esfandiari, who were all later released. (That same year retired FBI agent Robert Levinson went missing after last being seen on Iran’s Kish Island. Despite photos from his captors, his whereabouts are still unknown.)

• In May 2008, retired Iranian-American businessman Reza Taghavi was arrested on suspicion of supporting an anti-regime group. He was released more than two years later.

• In 2009, three U.S. hikers, also accused of spying, were arrested and ultimately released.

• Tajbakhsh was re-arrested in July 2009 amid post-election protests and a massive government crackdown. In March 2010, he was allowed a temporary release that was later extended, according to the website freekian09.org. The Iranian-American scholar is not allowed to leave the country, the website says.

• Journalist Roxana Saberi was arrested in January 2009 and convicted of espionage in a one-day trial that was closed to the public. She was freed in May that year.

• Literary translator Mohammad Soleimani Nia was detained in January 2012

• Christian pastor Saeed Abedini was reportedly detained in September 2012

Last week, Iran released at least a dozen other political prisoners, including one prominent human rights lawyer. Then, on Monday, the government released dozens more prisoners.

“My wishful thinking was praying and hoping that Amir’s name was among that list of people that were released,” his sister Sarah said. “It wasn’t. But we’re not going to give up.”

Behnaz Hekmati made a tearful plea to Iran’s new president, in English and Farsi, parent to parent, she says, to let her son come home.

“It’s more than two years,” she said, “Just let Amir come home. … Amir didn’t do any crime, he didn’t do anything. Just let him to come home and make his family happy again.”