Hurricane season is months away, but the waters where hurricanes roam haven’t received the memo. Ocean temperatures in the North Atlantic are historically warm for this early in the year, raising the risk of a hyperactive storm season that could also be supercharged by a budding La Niña.

“This season should be full speed ahead, as there are no factors going against an active season,” Brian McNoldy, a senior research scientist at the University of Miami, told CNN. “We’ll likely have an anomalously warm ocean and neutral or La Niña conditions for the peak of hurricane season – all the things you don’t want if you want less Atlantic storms.”

Stronger ones, too. Warm water provides the necessary fuel not just to help storms form, but to also boost their strength.

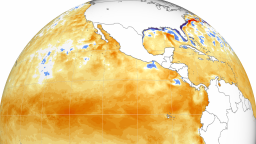

Sea surface temperatures across the North Atlantic Ocean reached a level unheard of for February earlier this month: 1 degree Celsius above what’s typical, and more akin to June than February. They were even higher in the part where most Atlantic hurricanes form, reaching July-like levels from West Africa to Central America.

It’s a continuation of record-smashing global ocean heat that started last March and hasn’t stopped since – driven by a super El Niño and global temperature rise from human-caused climate change, McNoldy said.

“(The heat) was so far above anything ever observed that it seemed impossible it would happen,” McNoldy said.

But it did. And ocean temperatures this year are off to an even warmer start than last year, including in the Atlantic, which could set the stage for a dangerous hurricane season.

“It’s February and a lot can still change. But if it doesn’t, then it could potentially be a very busy season,” said Phil Klotzbach, a research scientist at Colorado State University.

North Atlantic temperatures typically only go up from here, climbing in spring and reaching a maximum in early fall when hurricane season also peaks. And they are “almost certainly” going to continue to be warmer-than-normal into the summer, McNoldy said.

That forecast becomes even more alarming when paired with the likelihood of a La Niña – an ocean and weather pattern over the tropical Pacific that has a tendency to amplify Atlantic hurricane season.

Tropical systems need several atmospheric factors to come together to form, but one of the most important is low levels of wind shear – upper level winds that, if strong, can rip storms apart or even keep them from forming in the first place. Wind shear in the Atlantic typically decreases during La Niña, making it easier for more storms to form, strengthen and potentially impact land.

La Niña’s timing matters, since the resulting changes in the atmosphere will not be instantaneous, according to Klotzbach.

It takes time for La Niña’s influence to percolate to the Atlantic. The earlier La Niña arrives, the sooner it would influence hurricane season.

“If you don’t want an active hurricane season, you would need La Niña to wait as long as possible to begin,” McNoldy said.

Forecasters with NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center believe La Niña could arrive as soon as summer, but more likely by fall.

It’s difficult to know what the combination of near-record ocean warmth and a La Niña could be capable of, since there has been no other hurricane season in which temperatures were this extreme, Klotzbach said.

The 2010 and 2005 seasons were two of the most active and included notorious storms like like Katrina, Rita and Irene. Both had neutral or La Niña conditions in place, “but (similar outcomes aren’t) a guarantee since the anomalies now are very much warmer than any other year in recent record,” Klotzbach said.

Last year’s very active season also had no perfect analog. It was under the influence of El Niño, which should have suppressed storm activity, but was partly neutralized by the record-warm Atlantic. Twenty storms formed – the fourth-most on record.

Even if the season starts without any of La Niña’s influence, abnormally warm waters could still mean we see storms develop quite early in the season, a concern echoed by both McNoldy and Klotzbach.

But an active season isn’t necessarily the same as an impactful season. Many of last year’s storms didn’t hit land or populated areas, but having more storms increases the chances of a high-impact landfall.

“The more darts you throw at a dartboard, the more likely some are to stick. So, when more storms develop, it becomes more likely some will make landfall,” Klotzbach explained.

It’s simply too soon to know with confidence that this season will be impactful, as “day-to-day weather patterns” steer storms toward or away from land, Klotzbach said.

However the upcoming season shakes out, McNoldy urged anyone located in hurricane-prone regions to do two important things.

“Pay close attention to each storm that develops and don’t get complacent.”