She was no more than 6 when she saw the black birds come for her family.

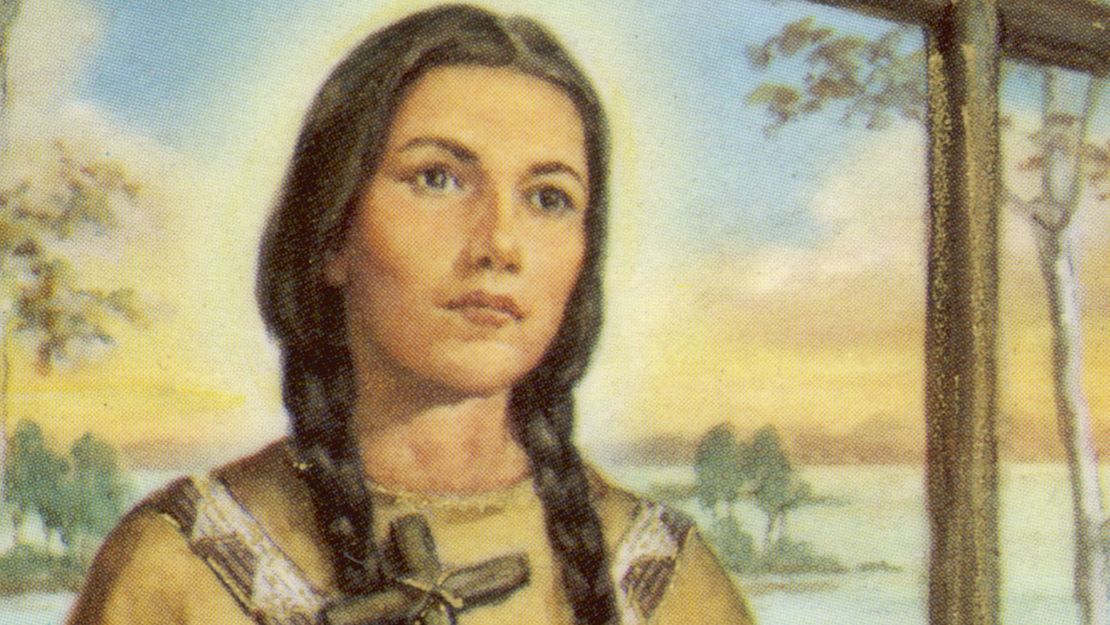

Her name was Kateri Tekakwitha, and she was a 17th century Mohawk girl living in what is now upstate New York. She had heard of a mysterious pestilence hitting distant tribes, but then it hit her village.

Red spots like berries appeared on the tongues of its victims. They turned into blisters that spread over the body, even appearing under the eyelids. Tekakwitha had no name for this mysterious affliction that would eventually kill her parents and her infant brother, and scar her face. She simply called it “black birds,” because “its beak eats my face.”

That’s how the author Diane Glancy describes the devastating effects of smallpox in her historical novel, “The Reason for Crows.” That pandemic was part of a biological catastrophe that eventually wiped out an estimated 90% of native peoples in North America.

“It was disease more than the cavalry that defeated the Indians,” says Glancy, an acclaimed poet who is the daughter of a Cherokee father and an English/German mother.

Now the black birds are gathering for Native Americans again.

This time it’s called the coronavirus, and it’s already been hammering other groups, like the elderly and African-Americans. But it poses a unique challenge to indigenous Americans – and it’s a grim reminder of one of their most painful historical traumas.

Why the coronavirus is so deadly for Native Americans

Native Americans are particularly susceptible to the coronavirus because they suffer from disproportionate rates of asthma, heart disease, hypertension and diabetes. Add to that lack of access to health care and pervasive poverty among the estimated 5.2 million people that identity as Native American or Alaskan native.

But there’s another fact that makes the coronavirus particularly menacing. Many Native Americans live in small and crowded conditions.

“You have a tinderbox,” says Kevin Allis, chief executive officer of the National Congress of American Indians. “The virus can get into a home or a couple of homes, and spread very quickly.”

In some native communities, that type of contagion may already be happening.

Read more from John Blake:

The Navajo Nation has seen at least 698 confirmed cases and 24 deaths. Tribal leaders recently enacted a curfew to combat the spread of coronavirus among its more than 250,000 members. And last week Cherokee Nation Health Services announced that 28 members had tested positive.

The virus also is taking an economic toll. Tribes are chronically underfunded. In recent decades some tribes have found a way to earn revenue by building casinos, but the epidemic has shut them down.

“Many tribal governments don’t have a tax base,” Allis says. “There’s no property taxes. There’s no sales taxes. There’s no income taxes. They’re not generating money for taxes. The only revenues they generate from tribal governments come from their businesses. So when you pull that rug from under us, we got nothing.”

Then there’s a cultural reason for why Native Americans are so vulnerable.

Across the globe the elderly are particularly susceptible to the virus and sometimes must be separated from other age groups for their protection. But that would violate a core value of Native American culture, Allis says.

“Elders are revered in our community,” he says. “They’re the people we turn to for wisdom and advice. A lot of times, it’s not the parents who will teach the traditions, and way of life. It’s the grandparents.”

A myth about the European conquest of America

Yet what ultimately separates Native Americans from other groups battling the coronavirus epidemic is their history. No other people in the US has suffered from infectious diseases like they have.

That history may still be largely unknown.

Many people believe that when Europeans first arrived in North America in the 15th century, they encountered a pristine, Eden-like wilderness inhabited by a few scattered tribes. That’s a myth, many historians say.

North America was a “tumult of languages, trade and culture,” the author, Charles Mann, wrote it in his book, “1491,” which looked at America before Columbus.” The continent was “immeasurably busier, more diverse and more populous than researchers had previously imagined,” Mann wrote.

Forget all of those popular images of a pre-Columbus America being filled with primitive tribes, historians say. In the 12th century the Mississippi Valley region – near the site of modern-day St. Louis – was home to an enormous city-state called Cahokia that dwarfed anything in Europe at the time, they say.

Cahokia was full of large earthen, monuments sculpted in the shape of gigantic lizards and a 1,330 foot-long serpent. The city was more populous than London at the time, according to “An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States,” by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz.

Some of the first European explorers to North America were awed by the sophistication and size of the settlements they encountered in North America, Dunbar-Ortiz wrote. The people impressed them, too. Many of the Native Americans towered over the Europeans, and explorers marveled at their physical strength and ingenuity.

Those Europeans brought more than awe with them, though. They brought diseases such as smallpox, measles and influenza, illnesses for which many Native Americans had no immunity. A wave of epidemics followed, hitting some tribes so hard that villages became full of untended dead.

The lack of immunity, though, doesn’t fully explain why large regions of the US that had been inhabited by Native Americans were depopulated by the mid 17th-century.

The genocidal warfare Europeans waged against Native Americans made them more susceptible to disease, Dunbar-Ortiz says. And the epidemics and warfare fed on one another.

The Native Americans wouldn’t have been so vulnerable to diseases if white settlers were not trying to literally wipe them out. Their food sources were taken from them, their trade routes were cut off and many were enslaved. Dunbar-Ortiz believes this unrelenting physical and psychological assault depressed native peoples’ immune systems.

“If disease could have done the job, it is not clear why the European colonizers in America found it necessary to carry out unrelenting wars against indigenous communities in order to gain every inch of land they took from them,” she wrote.

Dunbar-Ortiz scoffs at the notion that Native Americans “just dropped dead” when they got near a European.

“That’s actually a narrative created to not deal with the fact of genocide,” she says. “You say it was no one’s fault because the only reason they succumbed had nothing to do with war or colonization.”

What happened to the Mohawk girl

Even contemporary Native Americas find it difficult to deal with the trauma of those epidemics and the losses that followed, says Glancy, the author and poet.

Some of that trauma has been passed down to modern-day Native Americans in the form of self-destructive behaviors, she says.

Native Americans suffer disproportionately from high rates of suicide, alcohol-induced deaths and violence against their women.

“There are diseases outside the physical ones,” Glancy says. “I consider alcohol and drugs a pandemic among Native communities.”

Glancy believes that trauma is why some Native Americans find it difficult to talk about the past.

“There’s a sense of shame, of being the loser. There’s a sense of having been stripped,” Glancy says. “You just want to cover again because it’s hurtful to talk about everything that was lost and will never come again.”

Glancy decided to delve into that trauma after she saw an image of a girl amid the decorative features at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. It was Tekakwitha – the Jesuits had converted her.

Glancy started researching and learned Tekakwitha’s fate.

The girl survived the smallpox, but it left pockmarks on her face, and she wore a blanket to cover her face for the rest of her life. It was a short one. She died at 24.

But people didn’t forget her. She impressed people so much with her fortitude and her faith that she eventually became the first Native American to be canonized as a saint by the Roman Catholic Church.

Reading about that loss in the age of coronavirus makes it even more haunting. At one point in Glancy’s book, Tekakwitha laments she is not strong enough to help her dying villagers.

Her fear is palpable. Nature itself seemed to have turned against her people.

“The forest holds us in its teeth,” Tekakwitha says. “The forest is a lion.”

Today, five centuries after epidemics almost wiped them out, Native Americans are facing another unseen predator. There are curfews, mysterious deaths and yet another epidemic plaguing a people who have already suffered so much.

The black crows have returned.