Editor’s Note: Elie Honig is a former federal and state prosecutor and currently a Rutgers University scholar. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

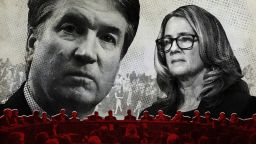

In the wake of a contentious and chaotic hearing on Friday, the Senate Judiciary Committee formally requested that “the administration instruct the FBI to conduct a supplemental FBI background investigation” relating to the nomination of Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. The committee specified that the investigation must “be limited to current credible allegations against the nominee” and must be completed within one week.

President Donald Trump authorized an investigation and declared that the FBI would have “free rein” to investigate. However, according to CNN, Senate Republicans have tried to at least influence the scope of the investigation by submitting to the White House a list of witnesses to be interviewed, though the list reportedly is not exhaustive or exclusive of other potential witnesses.

The FBI investigation, if not artificially and unduly restrained by the White House and if conducted in a thorough and impartial manner, is the best hope to provide the Committee with crucial evidence to enable it to move beyond the partisan “he said, she said” stalemate that boiled to the surface during Thursday’s hearing.

First, some clarification is necessary as to what the FBI does and does not do. Senate Republicans, curiously resisting an investigation, repeatedly declared last week that the FBI “does not make recommendations” and “does not draw conclusions,” citing a fiery speech by then-Senator Joe Biden during the 1991 confirmation hearing of Justice Clarence Thomas (during which, notably, the FBI did conduct an investigation).

The FBI generally does not make formal, conclusory recommendations about whether a witness’s account is true or false. FBI agents do, however, exercise judgment to determine which witnesses and leads are credible enough to merit follow up and which are not.

Beyond its core fact-finding mission, the FBI also performs an essential logical and deductive function. FBI agents don’t merely gather evidence in a vacuum; they connect the dots. They obtain evidence, and they make strategic determinations about how that evidence can be tested, how it might be corroborated or disproven and whether it might lead to additional evidence.

After several long days of heated partisan wrangling and confusion about how to determine the truth when two people offer starkly contrasting accounts, one commonsense notion ultimately prevailed: more facts and more information can only aid in the search for truth. We almost certainly will never have definitive proof one way or the other on the veracity of Christine Blasey Ford and Kavanaugh’s testimonies. However, every piece of evidence moves us closer to the truth by either corroborating or undermining key elements of both accounts.

Indeed, this is how prosecutors and law enforcement agents operate in real life. We dig in and look at all the facts surrounding and underpinning the allegation and the denial. Ultimately, upon further investigation, a case that initially appeared to be “he said, she said” can emerge as either a chargeable case or a case that does not merit prosecution.

Of course, we are not in a criminal trial setting, so the normal prosecutorial burden of “proof beyond a reasonable doubt” does not apply. The Senate is not bound by any particular burden of proof, but it seems that some lesser but still convincing showing – some have suggested a “preponderance of evidence,” meaning “more likely than not” – should tank Kavanaugh’s confirmation.

Here are three primary investigative steps the FBI should take to develop the facts necessary to assess who told the truth:

1. Interview Mark Judge

Judge was, according to Ford, the third person in the room when Kavanaugh allegedly sexually assaulted her. To some extent, we know what Judge is likely to say because his attorney submitted a cursory statement to the Committee last week, and Judge himself submitted a similar letter to the Committee after Ford testified on Thursday. Most importantly, Judge wrote that “I do not recall the events described by Dr. Ford in her testimony before the US Senate Judiciary Committee today. I never saw Brett act in the manner Dr. Ford describes.”

In his testimony, Kavanaugh subtly mischaracterized Judge’s statement as “refuting” Ford’s testimony. Not necessarily. First, the statements in Judge’s letter might or might not be true. We do not know yet because Judge’s account has not been meaningfully tested. Without in-person questioning by the FBI, there is little basis on which to assess the veracity of Judge’s account.

Perhaps Judge will stand up to questioning and back up his claim, or perhaps live questioning will expose gaps or inconsistencies. Either way, a live interview with the FBI will provide more answers and will move us closer to the truth than a conclusory, one-page, untestable written submission.

Even if the statements in Judge’s letter are technically true, they do not necessarily refute Ford. If Judge – who long has struggled with addiction – drank to the point of memory loss that night, then Ford could indeed be telling the truth and Judge also might “not recall the events described by Dr. Ford.”

The FBI needs to conduct a probing examination of Judge, including the following questions. Did you ever drink to the point of blackout? To the point of vomiting? Did Kavanaugh? Did you or he ever do so during the summer of 1982? How often? Is Kavanaugh any part of the inspiration for the “Bart O’Kavanaugh” character in your book, who vomited in somebody’s car and “passed out” after a party? Did you or Kavanaugh or your other friends ever drink at Tim Gaudette’s house? (More on this below). At other houses? Did you or your lawyer have any contact with Kavanaugh, any of his representatives or anybody from the White House, since Kavanaugh’s nomination? If so, what did they say to you?

An interview of Judge will shed important light on Ford’s allegations. If Judge credibly states that he did not drink to the point of blackout, and that he knows the event described by Ford did not happen, then he seriously undermines her allegation against Kavanaugh. (Though, as Kavanaugh’s longtime close friend, Judge’s impartiality would be in question). If Judge did drink excessively or otherwise has memory gaps from the summer of 1982, then his testimony neither incriminates nor exonerates Kavanaugh.

And if Judge confirms that Kavanaugh did drink to the point of blackout or memory loss, then (1) Kavanaugh’s denial that he attacked Ford loses much of its credibility, because he might well have drank to the point of memory loss on the night of the attack, and (2) Kavanaugh’s own Senate testimony that he did not drink to the point of blackout is false.

Indeed, Kavanaugh himself seemed to recognize the stakes of the blackout-drunk line of questioning during last week’s hearing, as he conspicuously tried to dodge it. Kavanaugh memorably tried to evade Senator Amy Klobuchar’s question about whether he had ever blacked out by responding, “[y]ou’re asking about, you know, blackout. I don’t know. Have you?”

To that end, the FBI should speak with friends of Kavanaugh’s from his high school, college and law school days. The FBI also should interview the recipients of Kavanaugh’s 2001 e-mail in which he apologized for “growing aggressive after blowing still another game of dice (don’t recall).”

2. Interview witnesses to Ford’s prior statements

Before her testimony this week, Ford submitted to the Committee statements from four people to whom she had spoken about the sexual assault years before Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination. One friend wrote that Ford stated in 2013 that she “had been almost raped by someone who was now a federal judge.” Another friend wrote that Ford mentioned the experience twice, in 2016 and 2018, the second time providing Kavanaugh’s name.

A third friend wrote that Ford told her in 2017 that she had been assaulted as a young teen by a person who was now a federal judge. And Ford’s husband stated that she told him about the incident around the time of their marriage, approximately 16 years ago, and that in 2012 she discussed details of the assault, including Kavanaugh’s name, during counselling sessions.

The therapist’s written notes from 2012 confirm that Ford mentioned that she had been attacked by a student from an elitist boys’ school who had gone on to become a highly respected member of Washington, D.C. society. The notes do not specifically name Kavanaugh.

The FBI must interview all three of Ford’s friends, Ford’s husband and the therapist. (Of course, as with Judge, the impartiality of these witnesses could be questioned because of their personal relationships with Ford). The FBI should probe whether and under what circumstances Ford made the statements; whether Ford’s friends told anybody else after hearing her account; whether Ford’s friends wrote any of their own notes or diary entries about her statements; whether any of the communications occurred over e-mail or text; and whether Ford ever made any contradictory statements to them about the alleged attack. The FBI also should probe whether Ford or her attorneys had any communications with Senate Democrats or their staffers about the written submissions.

As with Judge, the stakes are high here. If the witnesses withstand the scrutiny of an in-person FBI interview, their accounts provide crucial corroboration for Ford. The fundamental question arises: what possible reason would Ford have had to make up a false sexual attack and tell numerous people about it years before Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination?

Indeed, federal law recognizes the persuasive force of a witness’s prior consistent statements as an indicator of credibility. If, however, the witnesses do not hold up under questioning – if their in-person accounts are more qualified or less detailed than their written statements, or perhaps recanted entirely – then Ford loses crucial corroboration, and her credibility will suffer for having submitted their statements in the first place.

3. Investigate Kavanaugh’s July 1, 1982 calendar entry

During Thursday’s hearing, prosecutor Rachel Mitchell began to question Kavanaugh about his July 1, 1982 calendar entry. She abruptly stopped the line of questioning before reaching a conclusion, and, after a break, the Republicans changed course and abandoned Mitchell as their questioner. On Friday, Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse argued that Kavanaugh’s July 1 entry – which reads “Go to Timmy’s for Skis w/ Judge, Tom, PJ, Bernie, Squi” – corroborates Ford’s testimony.

Kavanaugh himself conceded on Thursday that “Skis” refers to “brewskis” (beers). And Ford testified that attendees at the party included her friend Leland Keyser, Kavanaugh, Judge (“Judge,” as noted on the calendar), P.J. Smyth (“P.J.” on the calendar), and another boy whose name she does not recall. Republican Senator Chuck Grassley responded that the calendar entry shows more people than Ford stated were present at the party. Neither side addressed the possibility that the original gathering – which Ford described in her testimony as a “pre-gathering” – grew after Ford left.

First, the FBI should interview all the people listed on the calendar, beyond Kavanaugh and Judge. Smyth already has submitted a written statement that he has “no knowledge of the party in question.” The FBI should ask whether Smyth can somehow rule out that such a party ever happened, or whether he simply does not remember such an event. Further, the FBI should ask Smyth whether he would have any reason to remember such a party if he did not know that anything unusual (such as an assault) had happened. The FBI also should interview “Timmy” (identified as Tim Gaudette), “Bernie” (Bernie McCarthy) and “Squi” (Chris Garrett).

Ford’s testimony does not put any of these men inside the room during the assault, or even at the party at all – though any of them could be the fourth boy at the party, whose name she does not recall. So, their ability to concretely confirm or deny Ford’s account of the assault is limited. Nonetheless, these witnesses might either confirm or deny: that the party happened (and might confirm that the party started with four people and then grew), that they ever met Ford, that they heard something happening upstairs, and that Kavanaugh and Ford were drunk (and if so, to what level). As with Smyth, it is readily conceivable that they have no memory of the party if they didn’t know of the alleged assault – in which case it would be just another high school party to them.

The FBI also should confirm information about Gaudette’s house. Ford testified that she does not remember at whose house the party was held, but she did recall that she had spent the day leading up to the party swimming at the Columbia Country Club. Gaudette’s house is approximately 11 miles from the country club. The FBI also should inspect the interior of the Gaudette house to see if it comports with Ford’s account of the attack, including the fact that she walked from a small living room on the first floor up a narrow flight of stairs to use the bathroom, and then was pushed from behind into a bedroom.

Finally, the FBI should attempt to narrow down the time frame during which the alleged attack occurred. Ford testified that she saw Judge working at the Potomac Village Safeway approximately six to eight weeks after the attack. In his own book, Judge writes that he worked at a supermarket for a few weeks during the summer before his senior year (1982) to raise money for football camp. Kavanaugh’s calendar, in turn, establishes that the football team held camp during the last full week of August.

Get our free weekly newsletter

July 1 – the date at issue – falls within the time frame of six to eight weeks before football camp. The FBI therefore should obtain records from Safeway (if they still exist) to confirm whether Judge worked at Potomac Village in August 1982. If he did, then Ford’s testimony will be persuasively corroborated by Kavanaugh’s own calendar, by Judge’s book and by the independent business records of Safeway. The White House reportedly has tried to place the Safeway inquiry off limits to the FBI. Given the potentially powerful impact of the Safeway records, such a limitation threatens to prevent the FBI from fully putting to the test both Ford’s allegation and Kavanaugh’s defense.

Note that Ford never has claimed the assault happened specifically on July 1. It is possible the party happened on a different night or at an event not noted on Kavanaugh’s calendar. But there is no downside to the FBI determining whether this calendar entry is consistent with Ford’s account of the assault.

It unequivocally is a good thing that the FBI now has a chance to investigate. But it is essential that the FBI truly be afforded “free rein” to investigate, as Trump initially guaranteed. If the FBI is empowered to do a fair and unobstructed investigation, it certainly will discover more information, and in a more reliable manner, than the Senate has been able to obtain.

While it may be impossible ever to establish definitively whether Ford or Kavanaugh have told the truth, the FBI’s investigation has the potential to tip the balance one way or another. At an absolute minimum, the FBI’s investigation should reassure us that, while politics always rule in the United States Senate, the facts matter too.