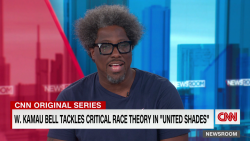

Editor’s Note: W. Kamau Bell is a sociopolitical comedian and author who hosts and executive produces the CNN Original Series “United Shades of America,” airing Sundays at 10 p.m. ET. The views expressed here are his. Read more opinion on CNN.

The average person who doesn’t have kids in school may not realize that being a teacher during a pandemic is like being a firefighter: Even when you’re sleeping, you might be awakened and called into duty.

Monique Davis is no different. As a special education teacher at Shaw High School in East Cleveland, Ohio, she’s always been at her students’ beck and call, and has long provided her phone number in case a student needed to reach out.

But during the pandemic, Davis has found her students in need sometimes into the early hours of the morning. Teaching during the crisis of Covid-19, she said, has made her “burn the candle at both ends.”

Yet when I visited her classroom last fall for an episode of “United Shades of America,” I would say she was already burning the candle at both ends, plus the middle, for her students. Her classroom was filled not only with the equipment the school provided, but also many, many things she had either brought from home or bought using her own paycheck.

Public school teachers across the country can relate. In the US, public schools are funded through a combination of primarily state and local, plus some federal resources – but some states are poorer than others, and some cities are poorer within those states. And when there’s that kind of inequity, teachers like Davis often step in to make up the difference.

I wanted to find out how things were going for Davis as she transitioned to virtual teaching during the pandemic. Below are excerpts from our conversation in June, lightly edited for length and clarity.

Kamau: Monique, I feel like I’ve gotta call you Ms. Davis, cause you’re a teacher and I will give you your respect.

Monique: Oh, it’s summer, (call me) Monique.

Kamau: What was it like to be a teacher in the midst of this? It started off like schools were going to be closed for maybe a week or so, and then it got extended, and then eventually we all realized this was going through at least the end of the school year. What was it like for you?

Monique: There was a lot of anxiousness at the very beginning because I didn’t want anybody’s grades to get messed up; I didn’t want anybody to get too lax. I didn’t want there to be that lag. I was very vigilant about getting in touch with parents, getting in touch with kids (and asking), ‘Hey, what are you doing? Are you getting work done?’

But as we saw it was going to be a more permanent thing, the vigilance had to turn into, ‘this is for the long haul.’ It turned into ‘slow and steady wins the race’ as opposed to ‘get it done now I want to see it.’

I have a lot of kids who kept in touch. My kids always have my phone number. If you’ve got my number, you always have a way to get in touch with me and to find out what you need and when you need it.

Kamau: You’re sort of ruining that idea that teachers have great hours: get there at eight o’clock in the morning; work till three; and then they go home and put their feet up.

Monique: Oh no. I felt for a while like I was burning the candle at both ends, because I had to be up during the day during my contractual school hours, but then my kids were teenagers and a lot of them were working so they weren’t getting off until 10 o’clock, 11 o’clock at night. And then that’s when I started getting text messages about, “How am I supposed to do this page?” Or, “Can you help me with this?”

So I started working later and later; I had one day where it was one, two o’clock in the morning and I’m just texting with three or four different kids. And it’s like, okay, normally this would be considered completely inappropriate!

Kamau: Teacher texts a student at two in the morning. That’s the headline of local news sometimes.

Monique: Right, right. But then I’m saying, “Okay, did you fill out your paperwork? Did you do the survey? Turn it back in. If you didn’t get the email, let me send you the link again.” So we went back and forth like that for almost an hour. And I was like, “It’s two in the morning; I need to go to bed.”

Kamau: And just to be clear, you can’t go to the school and say, “I worked some extra hours this week.”

Monique: Right.

Kamau: So there’s no, “Pay me for these extra hours.”

Monique: I started planning early morning appointments so that I could be available in the afternoon. Even my kids who weren’t working, they weren’t getting up and moving until one, two or three o’clock in the afternoon.

Kamau: Well, yeah, as a parent, it’s sort of hard to motivate your kids to get out of bed when they don’t have to be somewhere.

Monique: It was way more of: when the kids are ready, when the kids need me, that’s when I’m available. I even ran by a couple of houses, did some drive-bys. “I haven’t heard from you. What’s going on? What are you doing?”

Kamau: I know that the school you’re teaching at, I would imagine that some of the students don’t have the technology they need to keep up, or the Internet access. So maybe they have a smartphone, but they may not have a computer. You know, it’s hard to do everything on your smartphone. Can you talk about the digital divide?

Monique: Yes, we have a digital divide. That’s common in our district. But one of the things I did was to make sure that everything that I offer my kids was something that could be done on their mobile phone. The programs that I use at school, they regularly do them on their mobile phone, even during the day. We did some of that, and then our district also offered packets where it was paper and pencil. So you had an option to do it digitally or traditionally.

Either way, no matter what your needs were, they were met during this whole crisis.

Kamau: But the district did not have the resources to just give every kid a computer?

Monique: But if they don’t have Wi-Fi, then how do you use the computer? So what’s something we know we can do? Something everybody has, as opposed to assuming that people have Internet and they don’t.

And, you can have Internet one month, but as the pandemic drags on, you might not have it the next month because food is more important than Internet.

Kamau: Is it frustrating to feel like the problems of how we fund schools, and the divide between public schools in the inner city and public schools in the suburbs, is just exacerbated in the midst of this pandemic?

Monique: It’s frustrating. And it brings it to light. It’s ever more apparent, not just to those of us who live it every day, but now others are looking at it and saying, ‘Hey, we gotta do something about this. We need to figure out how to make this equitable for everybody.’

Which is what we have been saying for eons. Let’s just make it equitable.

Kamau: Yes. I think the word equitable is important. People sometimes get caught up on equality and it’s like, well, no, everybody has different sets of needs. We want to make sure everybody gets what they need.

One of the things me and my wife ran into as parents of kids who are doing distance learning is that it feels like there’s pressure to keep the kids on track academically. But sometimes the kids’ social, emotional growth is such that it’s like they can’t even take it in. You know what I mean? Are you dealing with the mental health challenge?

Monique: Oh, yeah. A lot of times on my Zoom calls with my kids, we just talked about what was going on in their lives, what they were doing, and how their siblings were getting on their nerves, or how some of them were looking for jobs, or they were having birthdays that they weren’t going to be able to celebrate. We did a lot of that.

We have an outside agency that comes in and does social work services in our building. So I linked up with her, and for some of our girls we got together and met once a week just to talk about some of the ever-evolving issues that might be going on. They were seniors and they were getting ready to graduate. There was not going to be a prom. And you know, for a lot of girls, prom is a big deal.

Kamau: And for kids who haven’t been able to keep up with the schoolwork, that summertime regression is going to be even more profound. What are you thinking about that?

Monique: That’s something we as teachers are always concerned about, but we figure it out. I have kids who are at multiple levels at any given time … you just meet kids where they are. You know, everybody’s not coming here ready to go every day.

You don’t know who’s maybe lost relatives to Covid. You don’t know who’s lost homes. Who’s lost jobs. There’s so much that kids come to school with sometimes, and learning isn’t the most pressing thing on their mind. So if you can get through some of the things that might keep them from learning, if you meet kids where they are, you can bring them along at their individual pace.