Editor’s Note: Daniel Brumberg is Co-Director of Democracy and Governance Studies at Georgetown University and a Senior Adviser at the United States Institute of Peace.

Story highlights

Daniel Brumberg: In absence of political vision in Egypt, looks like generals want to seize control

He says in symbolism, actions, Morsy government failed to show it stood for all Egyptians

He says Brotherhood has shown intolerance arrogance; government destroyed trust

Brumberg: Where is opposition's game plan, leaders with moral force, alternative to military?

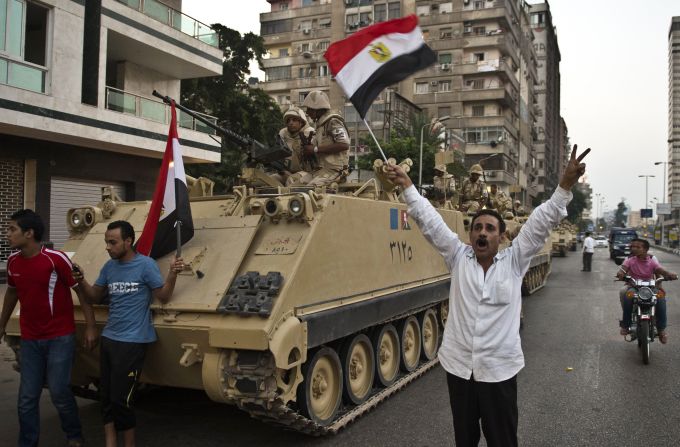

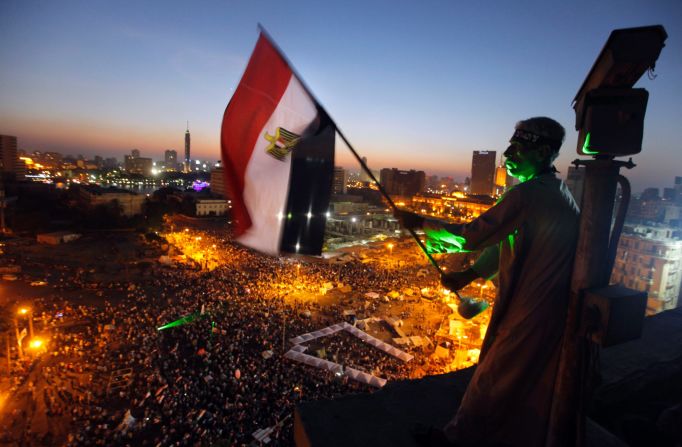

With the prospect of a military intervention in Egypt’s chaotic transition now looking inevitable, the generals are set to seize the mantle of leadership that others failed to grasp effectively. Their move suggests something much deeper than crass opportunism, though. Rather, it underlines one of the most striking features of Egyptian politics since the January 25, 2011, uprising: the absence of a political vision that might help unify the country.

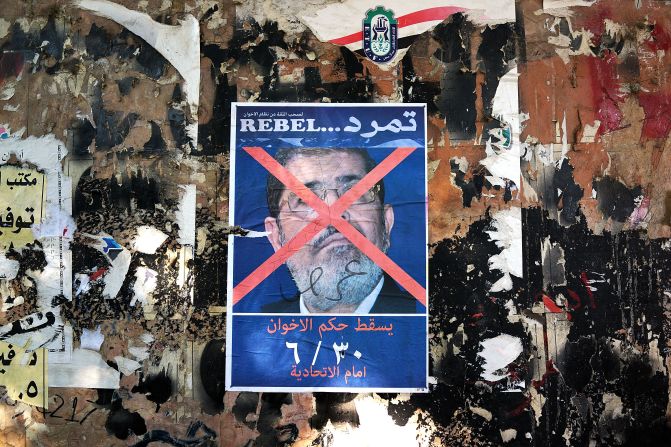

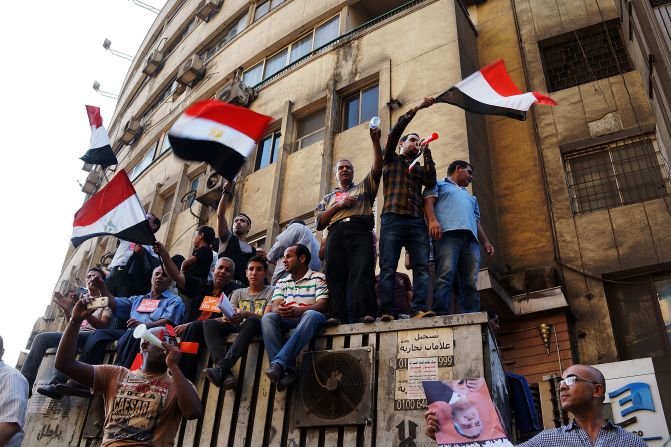

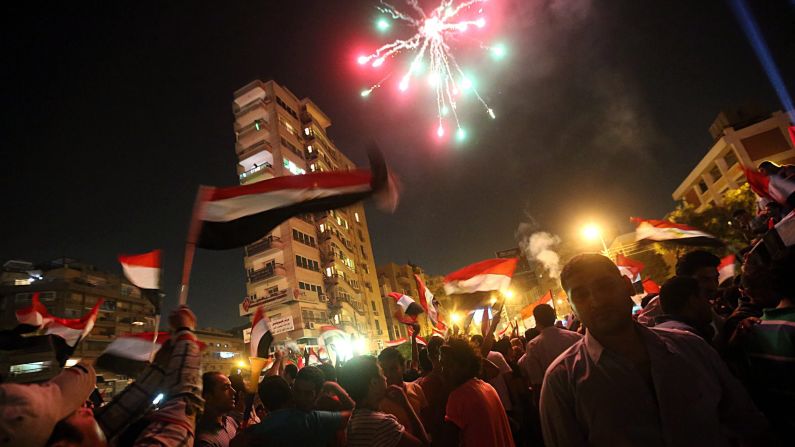

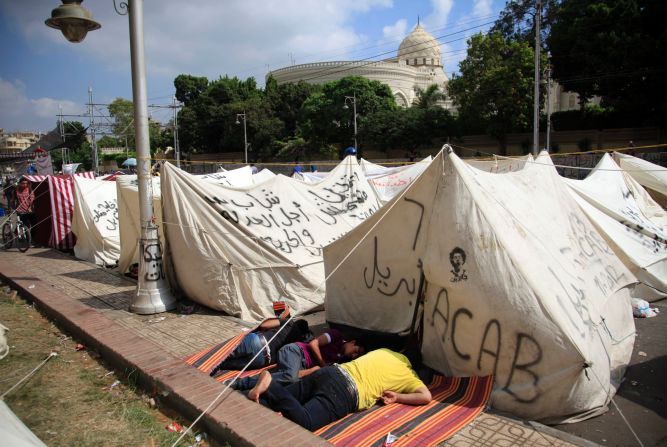

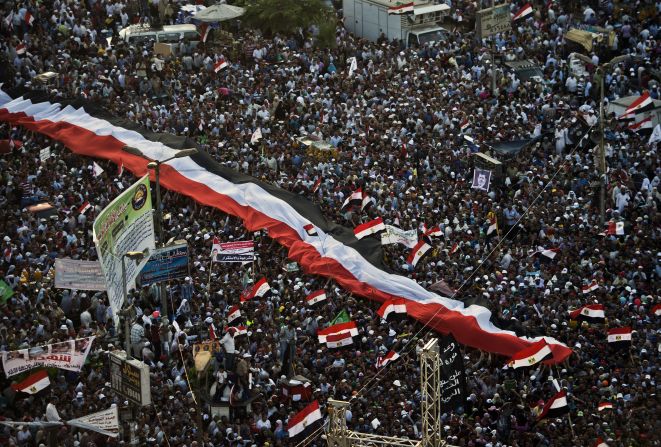

Yes, the generals will be sailing against the headwinds of a popular revolt that put millions in the streets. But by itself, the catharsis of empowerment that the Tamarud (Rebellion) Movement generated with the June 30, 2013, protests will not produce new leaders capable of deflecting the military’s renewed efforts to shape the course of political change.

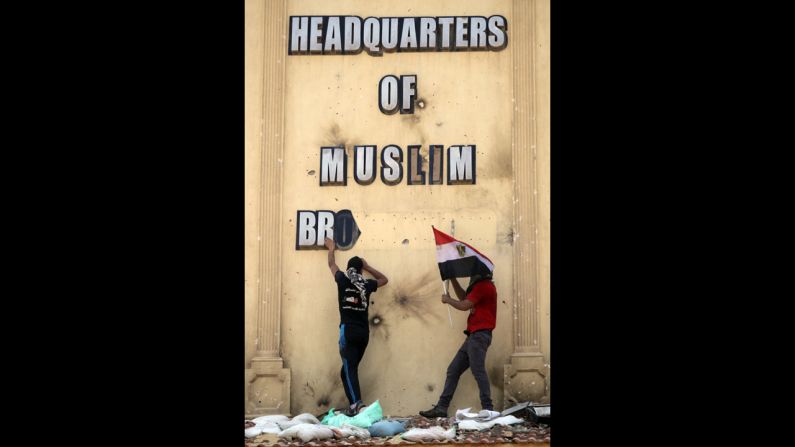

To appreciate the challenges facing Egypt we must first be clear who bears the most responsibility for this crisis: the Muslim Brotherhood and its Justice and Freedom Party. The Brotherhood failed to grasp the most important task of elected leaders in any society trying to define a new basis for democratic national unity: creating a symbolic language that promises inclusion and reconciliation.

As Invictus, the inspiring film about South Africa’s Nelson Mandela, demonstrates, this language is not merely about a perfunctory readiness to share power with rivals. Reconciliation must also be a pivot around public acts and rhetoric that reassures those who have most to fear from majoritarian democracy that they, too, will have a place under the post-authoritarian sun.

Ghitis: Egypt to Morsy: You need to go

It was on this level of symbolics that President Mohamed Morsy and his allies ultimately failed. This is why so much of the post-mortem analysis of the transition misses the point. The defenders of the Muslim Brotherhood have told a story of efforts to include non-Islamists in the Cabinet and the assembly that was drawn up to write a new constitution. But they are carefully selecting their details.

Despite Morsy’s inauguration day promise to represent “all Egyptians,” in the year that followed, Brotherhood leaders communicated intolerance and arrogance to both their secular rivals and their Salafi competitors. Such language reinforced the commitment of the Brotherhood’s rank and file to marginalize and humiliate their rivals. This came to a head in December 2012, when secular activists were taken hostage by Brotherhood activists and tortured. Widely available on the Internet, the videos of Brotherhood activists delighting in the pain and degradation of their prisoners destroyed what little basis of trust there might once have been.

But if the Brotherhood bears most of the responsibility for the current crisis, the leaders of the Tamarud Movement must face some tough questions. Having brought millions into the streets, what is your game plan? How will you transform a tactical victory into a strategic win? Where are the leaders who will give a new vision of politics in Egypt real moral force? Most importantly, how will you avoid signaling to all Egyptians –including the Brotherhood– that the price they must now pay for two years of bad leadership is another form of political exclusion or a political process ultimately controlled by the military?

This is what the Brotherhood ultimately fears. In point of fact, if under rule of Hosni Mubarak rule they were never fully excluded from politics, they were still prisoners of a system that denied them any hope of exercising real political power. Freed from such shackles by the January 25, 2011, revolt, they sought political vengeance.

But if the Brotherhood is at fault, the leaders of the June 30 rebellion now face the challenge of putting aside their own desire –or that of their followers –for score settling and focusing instead on building a grass-roots political party that can help Egypt back to inclusive democratic governance. Let us hope that out of the maelstrom of this latest crisis, one that has seen unprovoked abuse and needless violence on both sides, leaders capable of assuming this great task will not sit by and watch Egypt return to the past.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary Daniel Brumberg.