What do ceviche, pad thai and hot dogs have in common?

They’re all foods immigrants brought to the United States. And they’re among the many meals featured in Padma Lakshmi’s “Taste the Nation.”

In her 10-episode series streaming on Hulu, the cookbook author, model and longtime “Top Chef” host is tackling a tough question.

“What exactly is American food?” she asks in the show’s opening credits. “And what makes us American?”

Lakshmi came to the United States from India when she was 4 years old. And there’s one key ingredient she argues makes American food great: immigration.

To make her case, Lakshmi travels across the United States, focusing on different cuisines – and the people behind them – in each episode.

She samples burritos as border surveillance helicopters hover overhead in El Paso, Texas. She dines on dosas and swaps stories about growing up Indian-American with former US Attorney Preet Bharara in New York. She cooks kabobs and wanders through Persian market aisles in Los Angeles.

And along her journey, Lakshmi points out that foods now assumed to be American have immigrant roots. As she tours Milwaukee in an episode dubbed “The All American Weiner,” she notes that even famed meat company founder Oscar Mayer immigrated to the United States from Germany in 1873.

Gullah Geechee cuisine in Charleston, South Carolina, Chinese cuisine in San Francisco, Native American cuisine in Arizona, Peruvian cuisine in New Jersey, Thai cuisine in Las Vegas and Japanese cuisine in Honolulu are also on the menu in this season of “Taste the Nation.”

Lakshmi has been a vocal critic of President Trump and a prominent advocate for immigrant rights since he took office. But she’s hoping her show, like the food it features, will be a bridge crossing the political divide.

“The show was designed for people who don’t think like me, who don’t think that immigration is a good thing and are afraid of it or threatened by it. … I hope that this show gives them a clearer idea of what immigration feels like and looks like in a human way, on the ground, in people’s daily lives,” she says.

Lakshmi spoke with CNN this week about her own immigrant experience, how restaurants she visited are faring amid the coronavirus pandemic and the places and cuisines she’d like to explore next. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

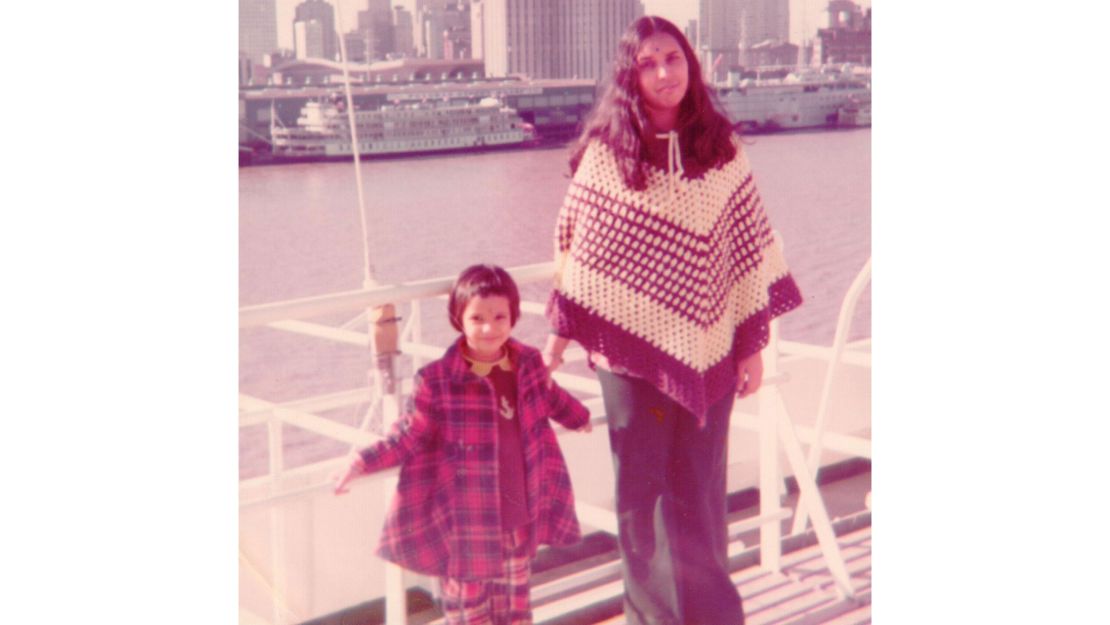

Every episode of “Taste the Nation” begins with you holding a photo of yourself as a 4-year-old who just immigrated to the US. What do you remember about those first days in America and what they were like for you? And how do you feel like that time shaped who you are today?

It was very exciting to come to New York as a 4-year-old from India. I was, of course, very happy to be joined with my mother. I had been separated from her for two years when I was a toddler. So that also informs my thinking about this issue.

I thought that New York was an exciting, wonderful place. I remember her taking me to the local A&P Market. And I remember thinking, “Oh, my God. Look at all this stuff.” The shops that my grandmother and I went to in South India were really small. They had one or two choices for what you needed. So all of that abundance really made a mark on me. At that time in India in the 70s, there was one type of sliced white bread…it was a knock-off of Wonder Bread, right down to the colors and the packaging. But we walked down this bread aisle and there were at least 15-20 different choices, just from the sliced breads. I’d never seen English muffins before. All of these things were just so overwhelming.

And there’s a moment when I go to the Tehran Market in the Persian episode (of “Taste the Nation”), looking at everything because I’ve never been to a specifically Persian grocery store before. And it’s the same feeling I had as a child of being totally overstimulated and not knowing where to look. It’s a sort of the Disneyland of food in both instances. So I’m glad I haven’t lost my childhood appreciation of a food market.

What is it like to be launching a show that focuses largely on restaurants and traveling around the US and immigration at a time when because of this pandemic, a lot of people can’t travel, a lot of restaurants are struggling and immigration has basically ground to a halt?

It’s very strange to be promoting anything at this time when there are so many pressing issues in our country to address. We filmed this show last summer, but it feels like a lifetime ago. I hope that the show will allow people to travel vicariously and eat out a little bit through the show and through the places I go.

What’s happening to the restaurant industry is devastating. But we will rebuild. They will come back. We don’t know in what form. Many will not come back. I have been in touch with a handful of the people and restaurants that we visit on the show to just check in on them and see how they’re doing. Some are open for takeout. Some are open for delivery or curbside pickup. Some are still shuttered because they don’t believe that they have a way to make food without putting their employees at risk.

I hope that in time of upheaval, and necessary uprising, food can be an example, a positive example of what’s great about immigration and what’s great about inclusivity and diversity and why we need all these different nationalities. To be able to offer them a haven and a chance at a better life will give us the ability to renew and refresh our economy and our culture. And we need that.

In a lot of episodes, you chat with people about their struggles growing up in the US and trying to walk a tightrope between two cultures. Former U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara talks about being bullied as a kid, and how he knew people growing up who’d rather be mistaken for another ethnicity than admit they were Indian. And you tell him that you changed your name briefly in high school, to Angelique. Why was it important for you to bring up that moment in your life and issues like this as part of the show?

Because I think it’s telling. You know, it’s a result of a symptom of not feeling totally accepted and welcome. And, you know, it’s something I’m kind of embarrassed about, but it’s something that I needed to reveal in order to be truthful with my own story in that episode, as much as I’m asking other people, in other episodes and communities, to be truthful about their experience and personal history.

It also allows all the people I went to high school with to know that it’s me.

When you made that decision at that time to change your name, why did you do that?

I think my name is pretty easy to pronounce, maybe not my last name, but certainly my first name. But people mangle it all the time, including every teacher who ever called attendance at the beginning of each school year in each class. So it was just a way to avoid that. And it was the only thing I could think of to make me less different, more approachable, more the same. I don’t know – it certainly didn’t work. I still looked like I look and still was the person I was – and am. But I think when you’re a vulnerable adolescent girl, you just want to seem non-threatening, or non-strange.

In the show, you don’t gloss over some of the shameful chapters of American history that are connected to many of the rich culinary traditions that you’re highlighting, like Japanese internment camps or forced migration and enslavement of people from West Africa or the Chinese Exclusion Act. Why did you decide to take that approach?

History matters. It’s important to know that the foods we love have a lot of baggage attached to them, and it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t love them or can’t appreciate them and enjoy them. But we should understand the origins of our collective cuisine in this country, because if you understand how food evolved in America, you understand how America evolved. And I think that’s interesting.

I’ve always been a history nerd and a food nerd. So I just took a gamble that other people would find it interesting too. I did not want to do another food show that was just kind of easy, breezy and lifestyle-y, for lack of a better word. I thought there were already some of those around and they kind of bore me now. There’s a lot of great food programing. I just wanted mine to be in as much as possible what I would want to watch. And it is.

A theme that runs through a lot of the episodes is the relationship between mothers and daughters. And your own mom and daughter even appear in one episode. Why did you want to include them in the show?

The show highlights knowledge of culture being passed down from mothers to children because that’s what actually happens in most homes, especially immigrant homes. It’s the way that we connect our children to our culture the most. I felt it would have been hypocritical to ask other families and communities to be vulnerable and allow me to embed myself in their homes, in their kitchens and really ask some very deep, personal questions, without being willing to do that for my own family or life.

A lot of immigrant communities are very insular. And a lot of them don’t want to talk about their own families or experiences because they have learned the hard way. They’re embarrassed or they think that it’s going to be ridiculed or used against them. And so asking these people – some of whom also don’t speak English fluently – to expose themselves in this way was a big ask on my part. And because they trusted me, I needed to trust my audience. I needed to do that as well and not be guarded. And I think that the show is a success because of people’s willingness to go out on a limb for me.

If you have a chance to do another season of “Taste the Nation,” what other kinds of food would you like to explore?

I’d love to go to Dearborn, Michigan, to talk to the different Arab communities there because, you know, there’ve been layers of immigration for the last 100 years, started by Henry Ford, who was looking for new factory workers for his auto plants.

I’d also love to go to Alaska. I shot in Alaska for a “Top Chef” finale years ago. And I loved it. And it’s a really strange and beautiful place that not a lot of people on the mainland get to visit. And there’s this huge Filipino community there. I’d really, really like to go in and discover that. The climate of Alaska year-round compared to the climate of the Philippines, that is very different. So I think that’s an interesting look.

What is one thing you learned while filming “Taste the Nation” that really surprised you?

You know, in any food show – “Top Chef” included, or “Planet Food,” or anything that I’ve done – you always have one food that you’re like, that was nice, but I don’t need to eat that again. But I have to say, I did not come across that. I really, genuinely enjoyed all of the dishes I was introduced to, including the pack rat (which Lakshmi samples in the episode focusing on Native American cuisine). I was lucky, because I have no poker face.

Given all the things you learned making this show and all the many chapters of your life leading up to this moment, if you could talk to 4-year-old Padma right now or to 16-year-old Angelique, what would you tell her?

I would say everything takes longer than you think. And life is beautiful. And you will find your way most by being who you really are.