The storm that struck the Edwin Fox on February 1873 might sound dramatic.

It’s one of many stories involving the vessel, which nearly 150 years later is the last surviving ship that transported prisoners from England to Australia – not to mention took passengers to New Zealand, ferried soldiers to fight in the Crimean War, moved cargo across oceans, and even played a role in New Zealand becoming stereotyped as synonymous with sheep.

Amid such a storied history, how the Edwin Fox ended up in a seaside town at the top of New Zealand’s South Island is equally dramatic.

Indian origins, global impact

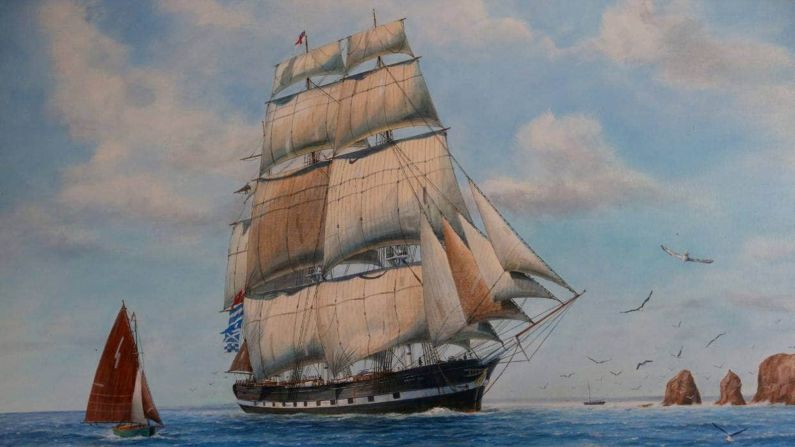

In the mid-19th century, the sun seemingly never set on the British Empire. Stretching worldwide, the towering masts and billowing sails of its fleet of merchant ships were as common a sight at ports as jet planes at airports today.

Amid that backdrop, the Edwin Fox’s origins are unremarkable. Karen McLeod, manager of the Edwin Fox Museum, says it was built in Kolkata – or Calcutta, as the Indian port was known then – out of teak, a wood prized for shipbuilding.

It was constructed in 1853 – making the Edwin Fox older than the Cutty Sark in London. At 157 feet (about 48 meters) long, it wasn’t large.

According to Adrian Shubert and Boyd Cothran, professor and associate professor, respectively, of history at York University in Toronto and authors of the upcoming book “Edwin Fox: The Extraordinary Story of How an Ordinary Sailing Ship Connected the World in the Age of Globalization,” ships like the Fox went where work was.

The convict connection

Though the Edwin Fox took part in events like the 1850s Crimean War (it transported soldiers; legendary nurse Florence Nightingale mentioned the vessel in a letter, but it’s unknown if she sailed on it), the ship might be best known for transporting prisoners to Australia. In fact, it’s the last surviving ship that took convicts to Australia.

In 1858, the ship was contracted to take prisoners from England to Australia. Among the convicts were William Tester and James Burgess, two of the four men convicted of the “Great Gold Robbery” in which about 12,000 pounds sterling worth of gold (about $1.88 million today) were stolen from a train in 1855 (later adapted into a Michael Crichton novel and movie starring Sean Connery and Donald Sutherland).

On board, prisoners were often shackled, in case they tried to take over the ship or escape. Despite the perceived danger, many guards brought their families along – three babies were even born on the voyage.

Dangerous as the Fox’s voyages were, there were no pirate attacks. McLeod notes the Edwin Fox wasn’t built for combat – it didn’t even carry cannons, though it had holes painted on its sides to make would-be pirates think it did.

England to New Zealand for $2,700 in tiny cabins

More than a decade later, the Edwin Fox again took people to the other side of the world. This time, they weren’t prisoners.

“The Fox delivered nearly 800 people to New Zealand,” explains McLeod of the voyages the ship took in the 1870s, which started in England and typically took three months, one-way. A number of New Zealanders can today trace their ancestry to immigrants who arrived on the Edwin Fox.

McLeod says a ticket usually cost 16 pounds sterling – about $2,700 today. But the conditions made even the most bare-bones economy class flights seem luxurious.

Cabins were cramped. The ship rocked about on the waves, especially in storms, one of which in 1873 resulted in multiple fatalities. Toilets were scarce. The food was usually terrible. The close, smelly, damp conditions meant disease was rampant. McLeod says one man even died after he broke his leg and couldn’t get adequate treatment.

“These were not worldly people (who traveled on the Fox), but I would say very brave,” she says.

“Some were conned into believing they had purchased land, and many were told things like New Zealand was a Pacific island with banana plantations where it seldom ever rained.”

Rebirth and rediscovery

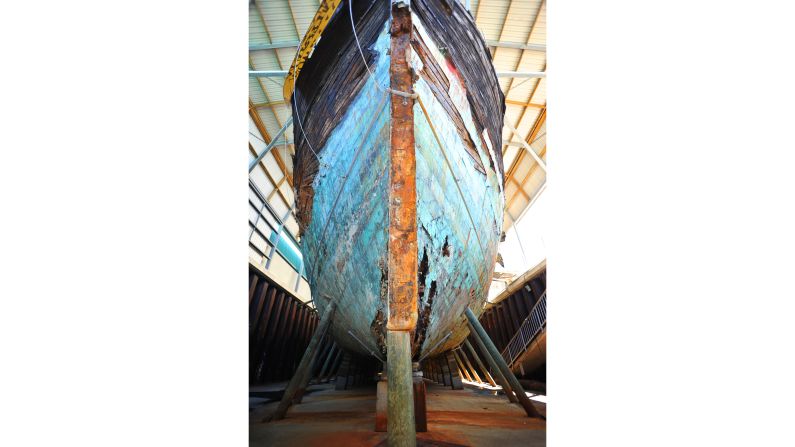

The invention of steam ships cut travel times between England and New Zealand to about six weeks. The Edwin Fox was repurposed as a freezing works for lamb.

First based near Dunedin on the southeast coast of the South Island (the largest of New Zealand’s main islands), the Edwin Fox was moved to the town of Picton, at the top of the South Island.

A new freezing works was built, and the ship was repurposed again. It was converted for storing coal – until that too, was disrupted by technological advancements.

Eventually, the ship was saved by the Edwin Fox Society, transferred to the Marlborough Heritage Trust, and today is at an eponymous museum in Picton.

McLeod says the museum has traditionally been more popular with overseas visitors. But with borders still mostly closed, more New Zealanders have been discovering the Fox.

It’s not just a relic of the past. Shubert and Cochran sum up the Edwin Fox’s continued relevance as “understanding what globalization meant in the 19th and early 20th centuries, that there were many losers as well as winners, and that it included many unexpected connections and consequences, is important to keep in mind as we try to understand the globalization we ourselves are living.

“The story of the Edwin Fox is a story for our times.”

Ben Mack is a writer from North Plains, Oregon living in New Zealand. His work has appeared in outlets including Vogue Australia, The Sydney Morning Herald and Newsweek.