Editor’s Note: Photographer and artist Chen Man is CNN Style’s guest editor. She has commissioned a series of features on visual language and imagining the future. Jonathan Glancey is an architecture critic and author.

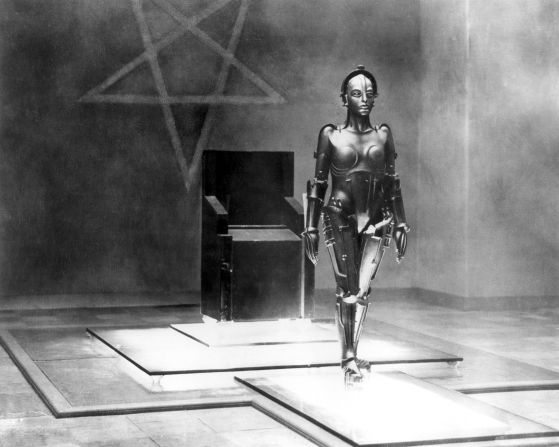

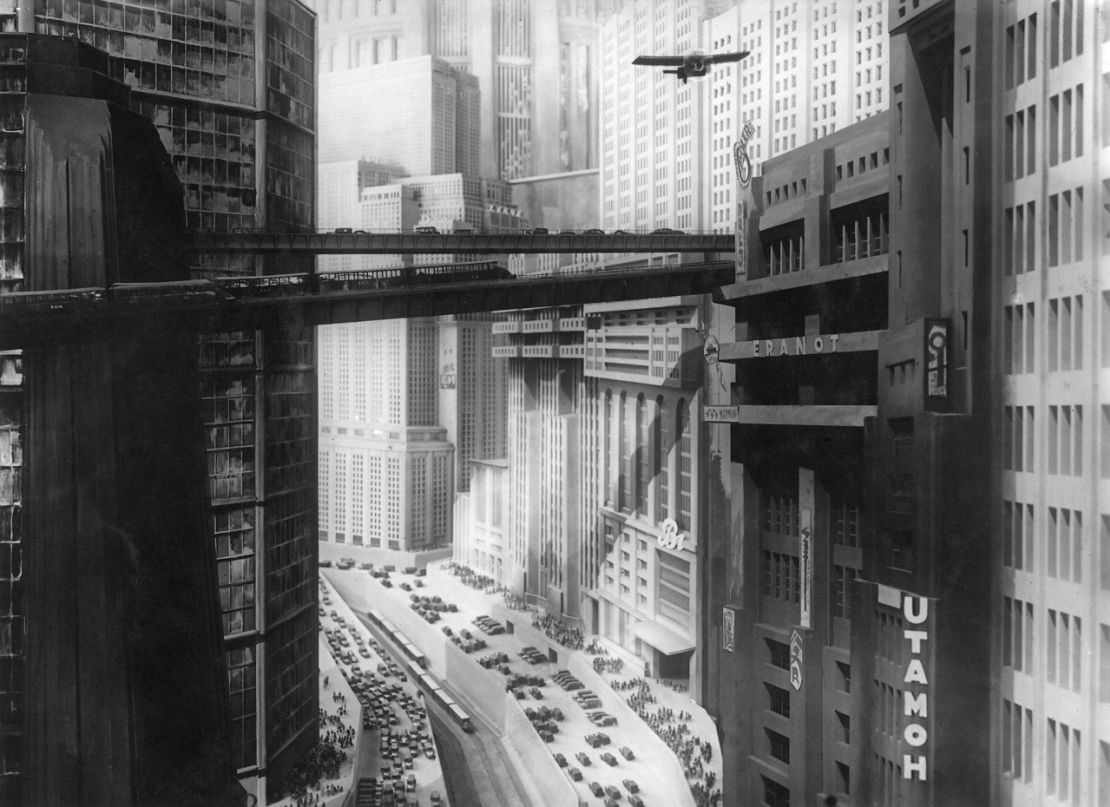

First screened in Berlin in 1927, Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” became a template for science fiction cinema. Its script and visual language established a tone later seen in films as varied as “Blade Runner” and “Star Wars,” “Logan’s Run” and “Aeon Flux.”

Regardless of how strong or weak the genre’s storylines are, its sets are rarely less than memorable. When critics question a science fiction movie’s credibility, it is often because design and visuals – especially in the age of readily manipulated digital imagery – appear much more important than the script or message.

Even when plots are thinner than celluloid film itself, it is still exciting to be transported through cities set far into the future, whether on Earth or light years away. Imagining remotely plausible buildings of the future is, however, hard to do.

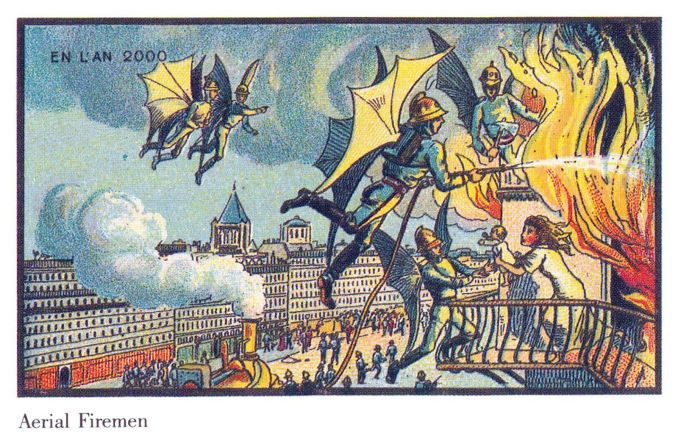

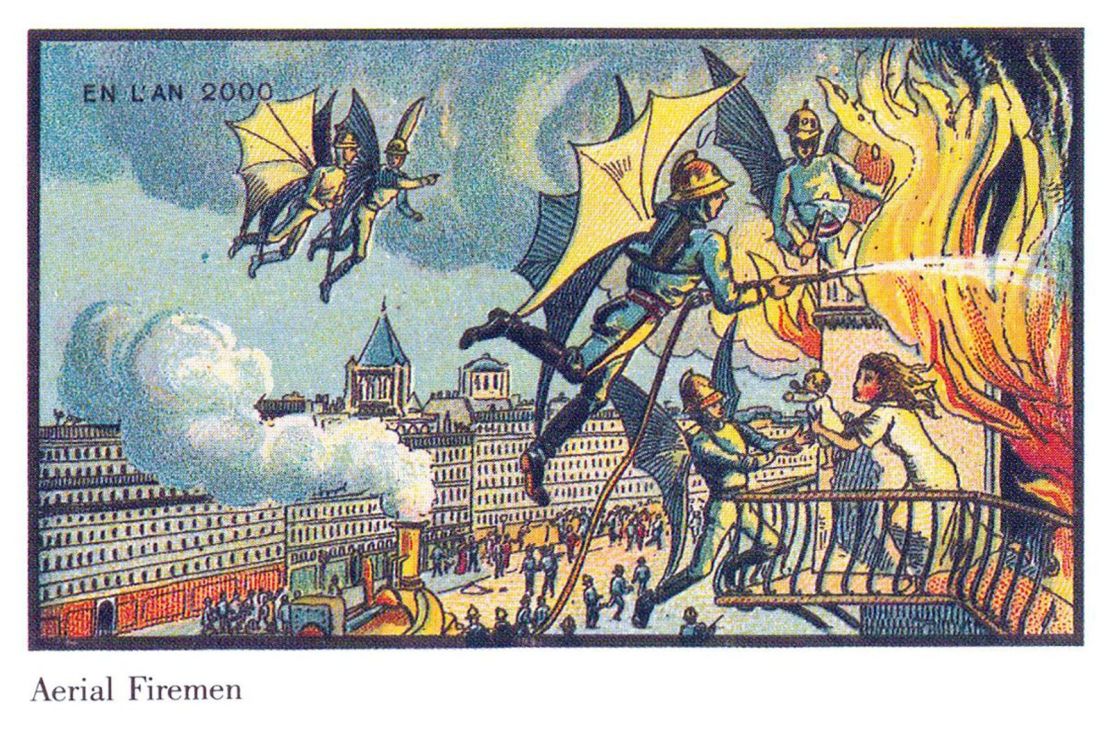

Look at 19th-century illustrations depicting Paris, New York or London in the year 2000. What you see are spiky Victorian cities blown dramatically out of proportion. Animated by trams, trains and improbable flying machines, these images often lack anything resembling a car, just as science fiction films until the 1990s were free of cell phones. New technology and design might be just around the corner, yet it can be hard to foresee.

Fritz Lang’s production designers – Erich Kettelhut, Otto Hunte and Kurt Vollbrecht – shaped the fictional city of Metropolis by re-imagining contemporary Manhattan. But they spliced the city with buildings inspired by avant-garde European architects – among them, Cubist architects from the Bauhaus School; expressionists, like Erich Mendelsohn; Le Corbusier, with his vision of high-rise cities; and, perhaps especially so, the Italian Futurist Antonio Sant’Elia, whose “Città Nuova,” presented his future city as a multi-level megastructure shot through with daring interconnecting bridges and vertiginous aerial walkways.

For the most part, 1920s cinema audiences had seen nothing like Lang’s future world. Yet the architecture it was based on had already been imagined. And this has been true of most science fiction films ever since.

Ridley Scott’s “Blade Runner,” released in 1982, depicted a “Metropolis”-inspired Los Angeles, set in 2019, that melded Manhattan and LA with the neon intensity of Hong Kong and the spirit of Tokyo. The interiors of the titanic Tyrell Corporation headquarters, a building at the heart of the film, were adapted from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mayan-inspired Ennis House, while the film’s opening sequence – featuring aerial shots of the city against a backdrop of industrial flames and haze – was inspired by Ridley Scott’s childhood in industrial northeast England.

Produced in 1976, “Logan’s Run” depicts a dystopian city of the future where citizens are killed off on their 30th birthdays to save resources. This youthful city resembled the kind of Olympic Games campus you could imagine existing in a former Soviet republic. The film was fun, though the sets proved not so futuristic after all.

Significantly, George Lucas adapted the bombing raid sequence of 1955’s “The Dam Busters,” also directed by Michael Anderson, to “Star Wars.” Far from offering a glimpse of the future, the “Star Wars” films are set in a faraway galaxy in the ancient past.

More recently, Karyn Kusana’s “Aeon Flux” (2005) presented the world in the year 2415. Survivors of a virus that wiped out 99% of the world’s population in 2011 live in a walled city – how medieval can you get? – evoked by sequences filmed in an abandoned 1930s wind tunnel and other Berlin buildings (including the sculpted Haus der Kulturen der Welt art center from 1957, the Bauhaus Archive from 1960, the crop-circle-like Tierheim Animal Shelter from 2002, and the haunting mid-90s Treptow Crematorium, with its subliminal references to the interiors of Ancient Egyptian temples).

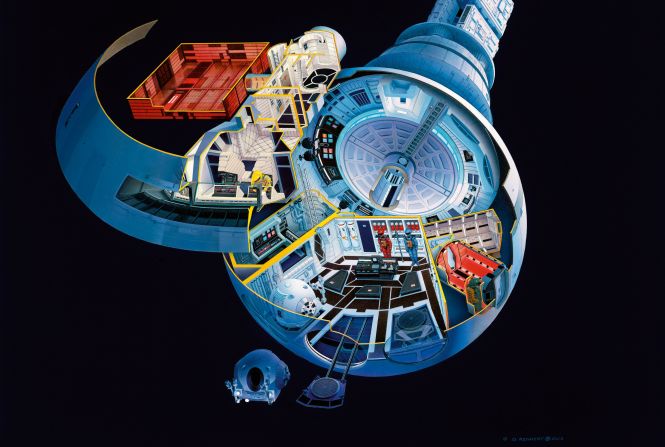

If science fiction films, with the honorable exception of Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” have tended to follow rather than lead architectural developments, has a director ever stepped completely out of the mold?

How filmmakers create future worlds

Andrei Tarkovsky did. With production designer Rashit Safiullin, the Russian director created a disturbing, haunting, dreamlike set for “Stalker,” a 1979 film focused on a restricted site called the Zone. Somewhere inside the Zone is a room where a person’s innermost desires are fulfilled.

But the Zone shifts and changes depending on the psyche of individuals. Tarkovsky and Safiullin gave form to this elusive and memorable setting in a deserted hydropower plant and a chemical factory in Estonia, proving that the architecture of the best science fiction films is more to do the imagination than with novelty and special effects. Today, “Stalker” is highly rated by audiences and critics alike.

The future, in films as in architecture, is never less than elusive and hard to predict.