In January, a fire tore through an historic building in the heart of Manhattan’s Chinatown, threatening to engulf decades of artifacts documenting Chinese life in the US.

The 130-year-old building, a former school turned community center, was home to the archives of the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) – the world’s largest archive of Chinese American history.

Some 85,000 items, dating from the late 1800s through the present, appeared doomed. Included in the varied archive was a Chinese typewriter from the 1920s, costumes used by the Cantonese opera clubs that proliferated in North American Chinatowns from the 1930s, and an 1883 document about the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first law to restrict a specific ethnic group from immigrating to America.

The floor that housed the collection was ultimately spared by the fire, though it was drenched with water during extensive firefighting efforts. Conservators said the items needed to be retrieved within days to save them from mold and water damage, and cultural institutions across the country reached out with offers of freezer space and expertise. However, city officials said the building wouldn’t be safe to enter for weeks. The roof and several floors had caved in, and experts worried the ceiling above the archive would collapse too.

Museum and community leaders were elated when, a few days later, the city declared that one archive room was safe to enter. MOCA put out a call for volunteers, and alongside several dozen employees from multiple agencies and contractors, spent two days removing around 700 damp boxes from the room – roughly 20% of the collection. The other 80% remained in limbo, however. If anything more was to be saved, it would have to wait for the building to be deconstructed, with the first phase of demolition not set to finish until the summer.

For the museum, this tragedy heralded an existential crisis – one that brought the institution back to its roots and inspired a community campaign to retrieve the remaining items. It also reaffirmed the museum’s core mission of encouraging people to consider Chinese American history as part of the larger story of America.

Building a collection

What is now called MOCA began during the late 1970s when two 20-somethings, Charles Lai and John Kuo Wei Tchen, began scavenging items from the streets of New York’s Chinatown, a community dating back to the 1870s. “I’d moved to New York because I wanted to learn about Chinatown history, and here it was being thrown out,” recalled Tchen, who is now a history professor at Rutgers University.

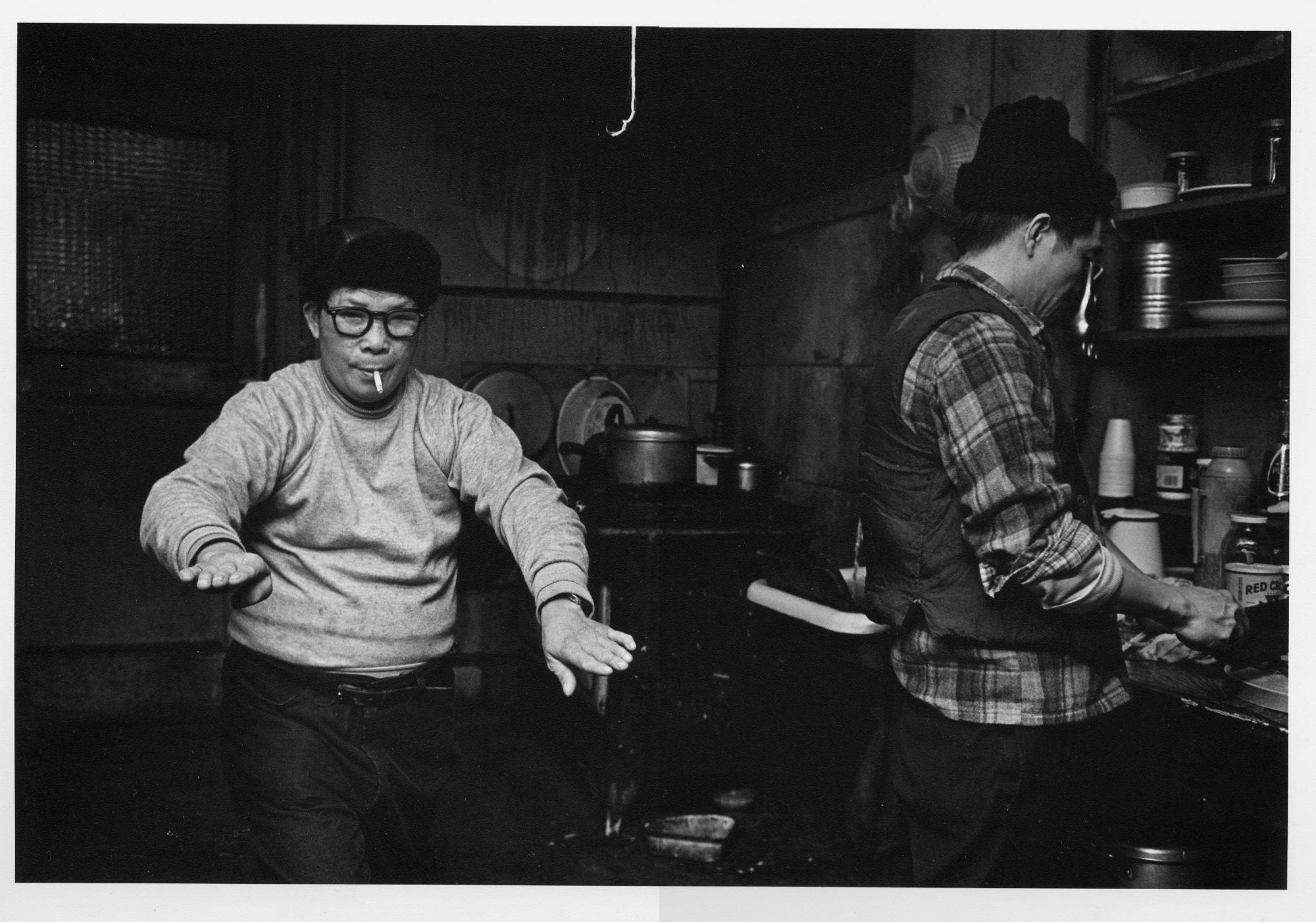

The pair saved items once owned by Chinatown’s elderly “bachelors” – men who went to the US when exclusionary laws still prevented women and family members from joining them, and who worked mainly in laundries and restaurants to send money back home.

When these bachelors died, the entire contents of their apartments would sometimes be left on the curb “because they had no one to pass them on to,” explained Tchen.

Around the same time, many of the city’s 99-year leases were expiring, meaning that old Chinatown businesses were closing down. Lai and Tchen rescued old medicine bottles, signs and even entire cabinets from century-old stores. Sometimes, they begged demolition crews to delay razing a building while they ran home, dropped off what they could, and ran back for more.

Tchen and Lai were rescuing what many people – including residents of Chinatown – saw as trash.

But through the years, as their efforts grew into the Chinatown History Project, and eventually MOCA, more people began recognizing the archive’s historical importance. It has since served as a resource for individuals researching their family histories, academics writing scholarly tomes and even creative artists like the Tony Award-winning playwright David Henry Hwang. (Hwang wrote his 1981 play “The Dance and the Railroad” with the help of research conducted at the project.)

The museum’s collection includes everything from 19th-century cheongsam dresses and rare instruments to the papers and possessions of Hazel Ying Lee, a WWII pilot and the first Chinese-American woman to fly for the US military. (MOCA president Nancy Yao Maasbach’s personal favorite is a Pan Am Airlines bag from Richard Nixon’s historic 1972 China trip.) Together, the items tell the 200-year-long history of Chinese immigration to America and, by extension, the history of America itself.

A community steps up

When MOCA’s staff learned that recovery efforts were coming to a halt, it organized a march and rally demanding that the city give the mission “urgent prioritization.” The announcement spread quickly through Chinatown, social media, community activists and cultural organizations. People gathered at the main museum building (which is separate from the archive building and was undamaged by the fire) to make posters reading “Save Our History” and “Don’t let our heritage rot away.” Elsewhere, the Asian American Arts Alliance partnered with community groups to raise over $14,000 for MOCA and the four other nonprofits affected by the fire, while Chinatown’s oldest store, Wing On Wo & Co., raised more than $9,000 for the museum through a silent art auction.

As it turned out, the march never happened: That same night, city officials promised that the collection would be rescued within the next week (Maasbach said she was told there had been a retrieval plan all along, but officials hadn’t wanted to share it yet). On March 8, dozens of city workers and contractors clad in hardhats and hazmat suits gathered at dawn to retrieve the rest of the collection, save for a wet pile of badly damaged cheongsams covered in dust and rubble, and a few other stray items amounting to less than 5% of the collection.

The items were whisked to a freezing facility north of the city, where they are still drying out.

Speaking by phone the following Saturday, Maasbach said it remains to be seen just how damaged everything is, but that, so far, most items appear to be in good condition.

The rescue happened just in time: Within two weeks, the specter of Covid-19 – which had already resulted in severe reductions in foot traffic for Chinatown’s businesses and institutions – saw the city put in lockdown, its museums indefinitely shut and MOCA’s programming suspended.

The thought of what was nearly lost makes Maasbach shudder, she said. “We fight every day to make sure people understand the mission of this museum, which is to tell these stories that aren’t told,” she added.

That mission seems even more urgent now, amid rising xenophobia, tensions between the US and China and increasing American nationalism that, as Maasbach put it, “views Asian faces as foreign faces, no matter how many generations you’ve been here.”

Maasbach estimates that drying, restoring and repairing the surviving items will take at least 18 months and cost more than a million dollars. Meanwhile, MOCA is shifting its programming online with podcasts, educational resources highlighting Asian American heroes and a social media campaign inviting people to share short videos about special objects that mean the most to them.

It also intends to keep collecting. “We see this time as critical because of the changing generations,” Maasbach said. “Chinese American seniors today have lived through civil war in China, changes of government, the Mao era, ‘one country, two systems,’ exclusion, the civil rights movement … the list goes on.

“We’ve been growing so much, understanding our place in the national narrative, trying to understand what that means, and understanding the boldness we need, while still retaining our humility,” Maasbach said.

She might well have been describing the journey of Asian America at large. The museum’s holdings are the tangible reminders of that journey – more than 200 years old, and filled with strife, achievement, heroes and tragedy.

“Nothing can replace looking at real artifacts, at family albums, hearing oral histories, seeing the documents from all these milestones in Asian history,” said Maasbach. “That’s the importance of this collection.”

The Museum of Chinese in America has launched a GoFundMe campaign for recovery and restoration efforts.

Top image caption: Two men, one smoking, one cooking, in their apartment on 68 Bayard Street in Manhattan’s Chinatown, circa 1982. The image was shot by photographer Bud Glick.