Aaron Celestian isn’t a big fan of “Ocean’s 8.”

“I have a hard time watching those movies because they’re always robbing museums,” he said with a laugh, standing amid a vault filled with some of the world’s rarest gems. “It’s really personal.”

It’s easy to understand why: As the curator of mineral sciences for the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles, Celestian oversees the Gem & Mineral Hall. Right now, the hall has some especially precious cargo in its current exhibition, “100 Carats: Icons of the Gem World.” (And in terms of the exhibit as a whole, “100 Carats” is quite the understatement: There are more than 3,000 carats on display through April 21.)

“These gems are just the true treasures of the world,” said jeweler Robert Procop, who organized the exhibition in collaboration with the museum.

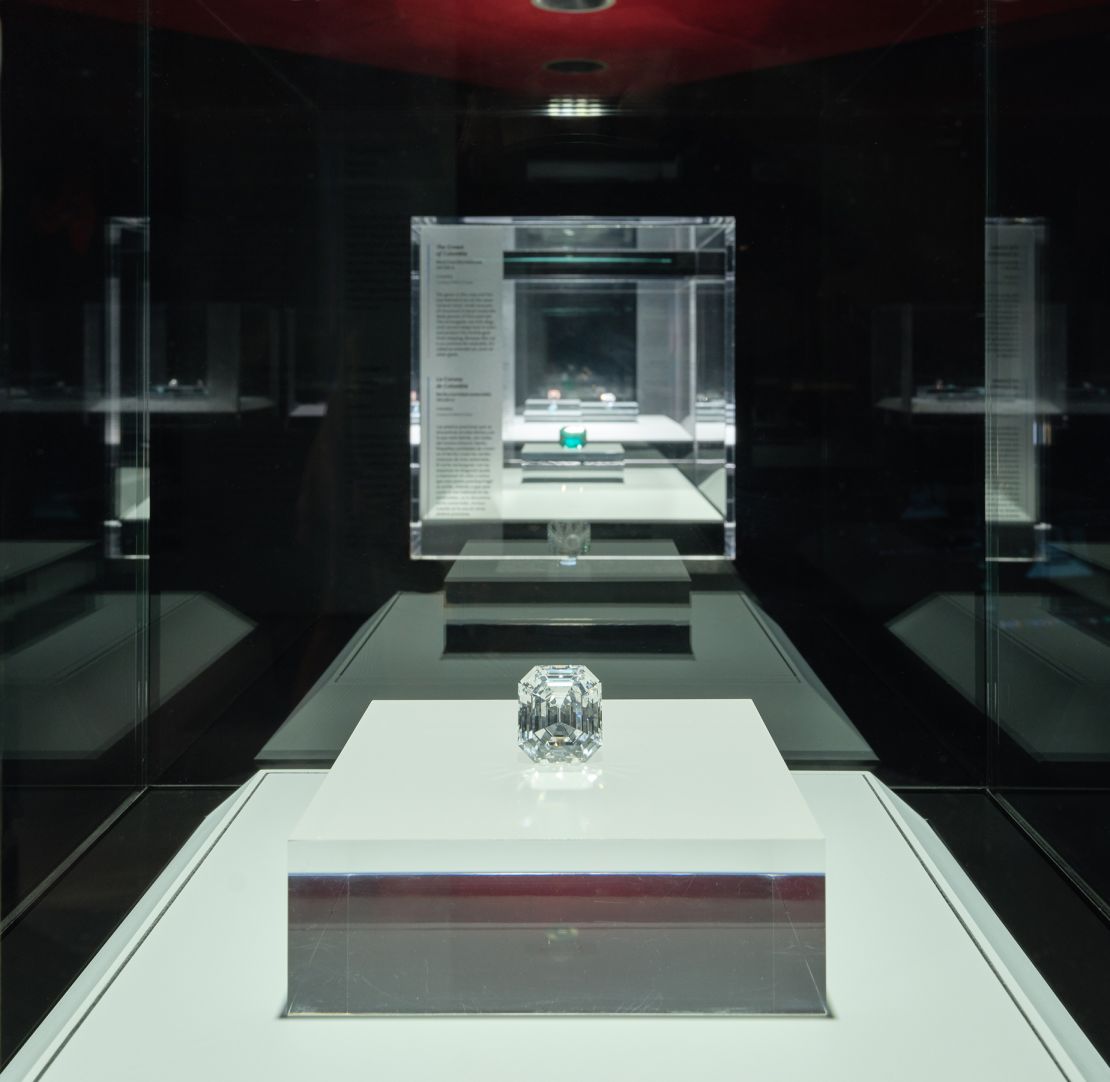

There are currently 17 massive gems on display inside of the hall’s Hixon Gem Vault — which is dutifully locked every night — and nine more pieces of jewelry adorn the walls outside. The centerpiece is the Jonker I diamond, a 125-carat stone that has, over the years, been passed through the hands of jewelers, royals and luminaries across the world.

The gem from which Jonker I was cut was discovered by diamond prospectors in South Africa in 1934.

“The story goes: It was raining one day… and then because all the rain just washed away the sediment, they found a 726-carat rough diamond,” Celestian said.

It was purchased by Sir Ernest Oppenheimer, who sold it to jeweler Harry Winston in 1935 for £150,000 (and shipped it from South Africa to New York City for 64 cents). Winston then had it cut into 13 pieces by Lazare Kaplan — one of the world’s most famous diamond merchants — with a tool coated in olive oil and diamond dust. The Jonker I was the largest cut.

“He sold it to King Farouk of Egypt in 1948,” Celestian said of the Jonker I. “The King had it for about four years… (before he) was deposed and exiled from Egypt.” At this point, Celestian continued, “the diamond went missing.”

Though the gem has been photographed alongside celebrities such as Shirley Temple, the public hasn’t had the chance to see it in person for many decades — since 1937, in fact, Celestian told CNN, “when it was on display at the American Museum of Natural History in New York for three days after it was cut.”

All that glitters…

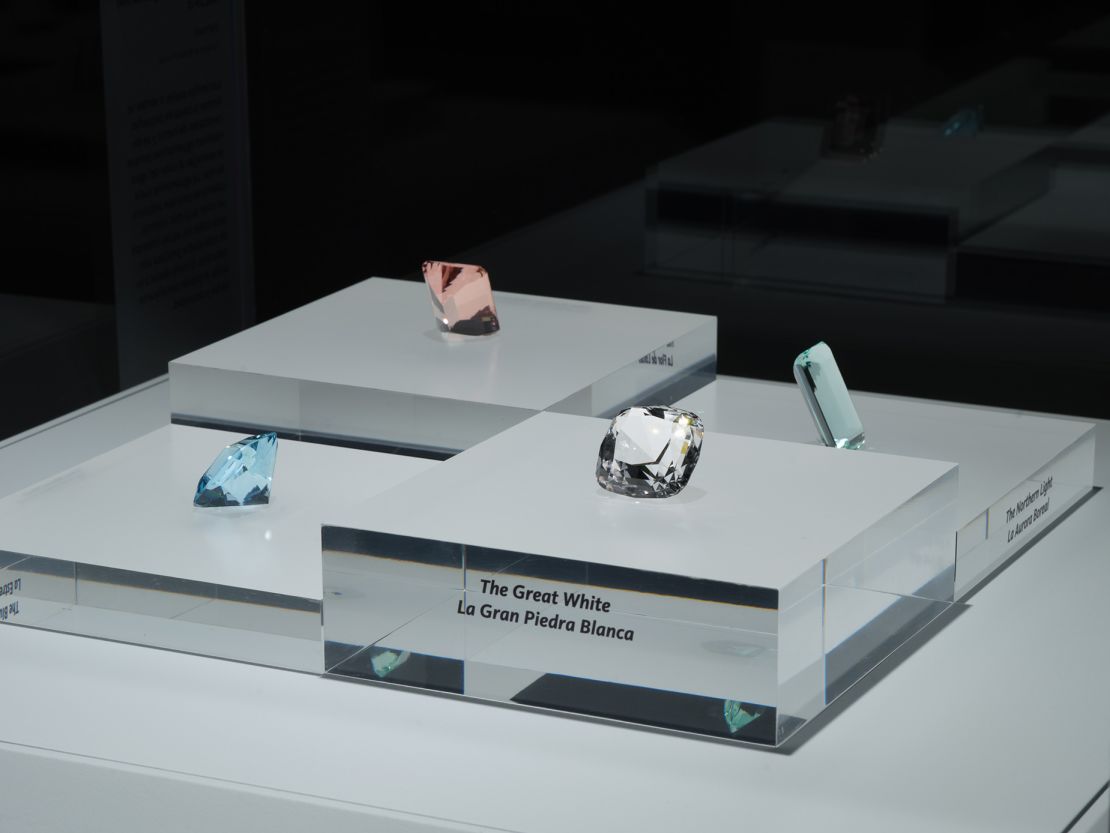

Even if your knowledge of luxury jewels ends with movies like “Uncut Gems” and “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” the exhibit is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see some of the world’s biggest, finest and most unusual natural stones. The gems that Procop and Celestian rounded up include a color-changing teal sapphire recently discovered in Tanzania, a 241-carat piece regarded as one of the most perfect “emerald cut” gems and an array of deeply saturated tourmalines.

Aside from the Jonker I, all of the gems in the vault are new discoveries unearthed and purchased in the last few years. Many are on loan from their (private) owners, while other pieces — and the jewelry outside the vault — were cut by Procop.

Procop — a jeweler for royalty and the uber-rich, known for collaborating on charitable projects with A-Listers just as Angelina Jolie, and whose work is also included in the Smithsonian’s collection — makes it sound like sourcing such gems is a piece of cake. With a trusted network of miners, brokers and buyers from around the world, he doesn’t have to hop on a plane to get his hands on a 100-carat piece. Rather, he can have them delivered right to his door, via armored trucks, of course.

But to understand the true significance of the gems in the exhibition’s vault alone, it’s helpful to know that carats (all 2,387 of them in there) are a unit of weight, not size. Rubies and sapphires, for example, are denser than diamonds, which means that a 1 carat ruby or sapphire will be smaller than a 1 carat diamond.

To convey that measurement to visitors, Celestian set up a display of gems that range from one carat to 100 carats, alongside a handy reference point for those of us who will never hold a huge gem: 100 carats weighs about the same as four nickels.

The exhibition’s educational display also has one of the world’s most precious gems hidden in plain sight.

“I always like to put little Easter eggs in the exhibits I do… in this case, it’s this one carat (gem) that is the world’s rarest gemstone,” Celestian said, pointing to a mineral called Kyawthuite. The reddish-orange mineral was discovered by a gemologist in Myanmar in 2010; “It’s the only one in existence that we’ve ever found,” Celestian added.

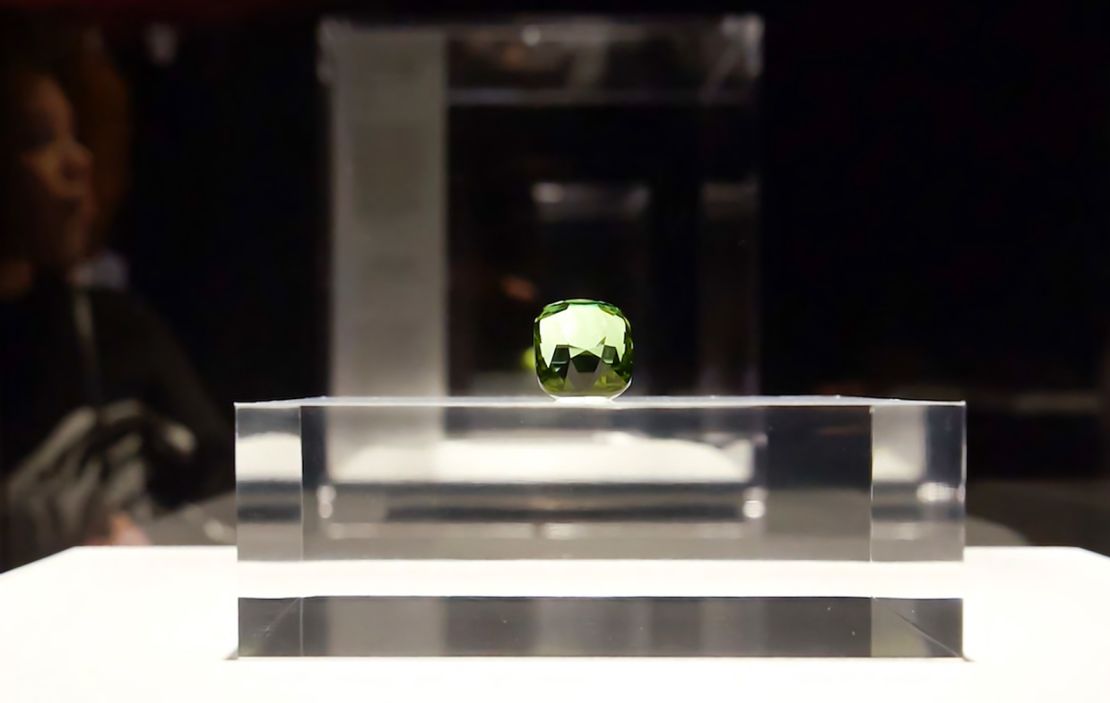

Though nothing else is quite as rare, the other gems in this exhibition are unique, vividly colored, and mostly unseen. “The Ukrainian Flag” is the largest bi-color topaz that’s been unearthed, “The Imperial” is the most exquisite green tourmaline ever found, the exhibit claims, and “The Crown of Colombia,” is the largest and most pristine emerald ever found in, as its name suggests, Colombia.

“To have something this clean, this transparent, and this big, and this saturated in color, is unreal,” Celestian told CNN of this latter piece.

Romancing the stones

The gems inside of the vault are all unmounted — to preserve them in their “purest form,” Procop explained — and displayed inside glass cases that allow viewers to appreciate their individual color, size and cut. The teal sapphire even has a display light that changes every few seconds to bring out the gem’s full color spectrum.

“When I had this in the lab, it was like, woah,” he said. “It was really incredible how the color was just changing.”

It’s unlikely that the gems will ever be under the same roof again. Those that belong to the museum will go back in their vaults, but the rest will return to their rightful owners. A few may also be put up for sale. In the meantime, the museum’s director, Lori Bettison-Varga, hopes that visitors leave inspired by the collection.

“As a geologist, that is what I absolutely love about sharing these gems: the geologic story, and what we can learn from these specimens,” she said. “And then the artistic, spectacular way that human ingenuity has brought them to life.”

It certainly never gets old for Celestian, who still finds awe in the beautiful stones that our planet has created.

“I’m an environmentalist — I feel strong and passionate about that — and I see these as a way of reflecting back on how we extract stuff from the earth,” he said. “To produce these magnificent stones, and to see them, is a reflection back on our own place on this earth.”