Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Paleontologists with the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History have discovered a previously unknown prehistoric species — a 270 million-year-old amphibian with wide eyes and a cartoonish grin — and its name is a nod to an iconic froggy celebrity.

Kermit the Frog meet Kermitops gratus, the most recent ancient amphibian to be identified after examination of a tiny fossilized skull that once sat unstudied in the Smithsonian fossil collection for 40 years, according to a paper published Thursday in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

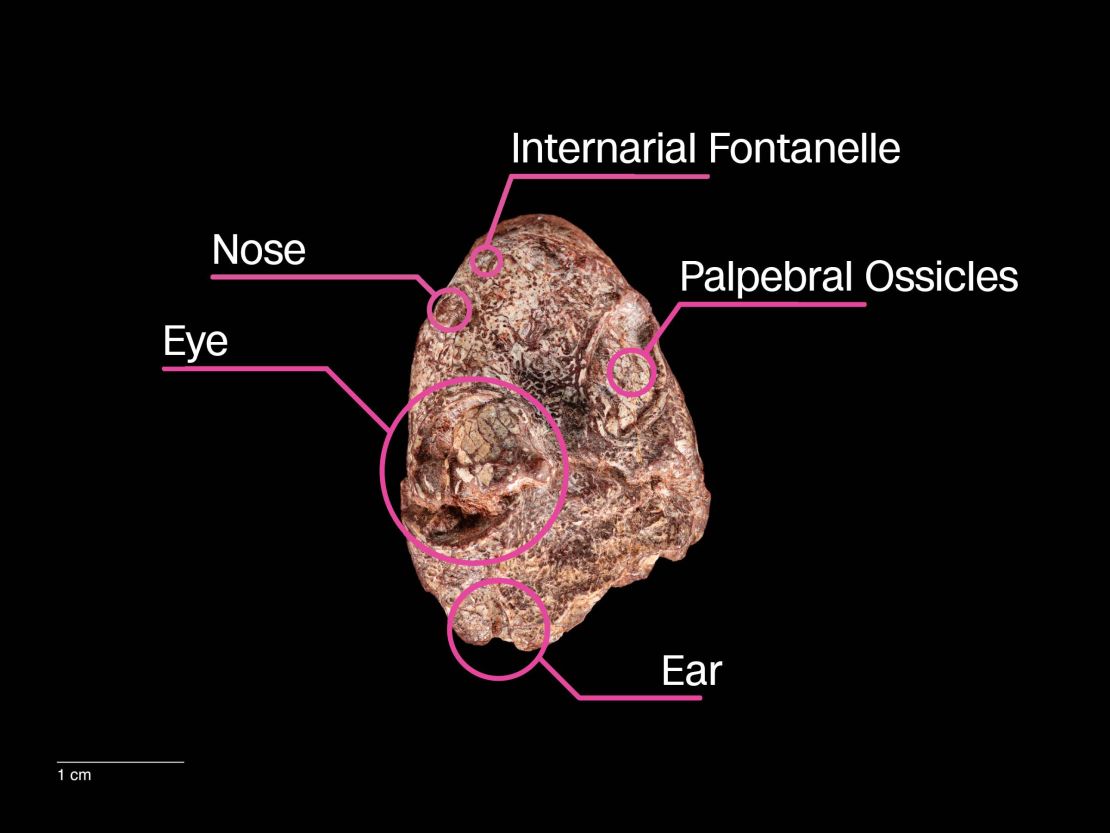

Predating the dinosaurs, Kermitops is believed to have roamed the lower Clear Fork Formation of Texas during the Early Permian Epoch 298.9 million to 272.3 million years ago. The skull of the ancient amphibian, measuring just over an inch (about 2.5 centimeters) long, features big oval eye sockets and — due to its slightly crushed state — a lopsided smile that researchers said reminded them of the Muppet icon.

The discovery of the new amphibian species could provide some answers to how frogs and salamanders evolved to get their special characteristics today, the authors wrote in the paper.

“One thing that Kermitops really shows is that the origins of modern amphibians are a little more complex than some of the research has led on,” said study coauthor Arjan Mann, a postdoctoral paleontologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

“And that really means that people need to keep studying these things because just looking at museum collections, like this fossil, has the potential to change our ideas of evolutionary hypotheses of living lineages.”

Kermitops, not a frog

The fossil was first uncovered in 1984 by the late Nicholas Hotton III, a museum paleontologist who had excavated fossils from the Red Beds in Texas, an area known to be rich in Permian-age remains.

Researchers unearthed a large cache at the site, including the remains of ancient reptiles, amphibians and synapsids, the precursors to mammals. The resulting collection included so many finds, paleontologists could not study a number of the specimens, including the newly named Kermitops. That changed in 2021, when the skull caught the eye of Mann, a postdoctoral fellow at the time, who was sifting through the Texas collection to see whether any notable specimens had been overlooked.

“Not only was (the skull) well-prepared by somebody, but it had features that distinguished it from anything else in the group that I’d ever seen,” Mann said. In early 2023, Calvin So, lead author of the new paper and a doctoral student at George Washington University, began to study the skull for a doctoral paper.

Kermitops is not classified as a frog because the prehistoric amphibian does not share all the same traits and anatomy found in modern frogs, So said. But the researchers determined the specimen is from the group temnospondyls, which are believed to be the most common ancestor of all lissamphibians — a category that includes frogs, salamanders and caecilians, Mann added.

The researchers noted several features that the ancient amphibian shares with its modern-day relatives, including a similar location for the eardrum at the back of the skull, a small opening between the nostrils that produces a sticky mucus to help frogs catch their prey, and even evidence of bicuspid, pedicellate teeth that are unique to amphibians and are found in most modern amphibian species.

Features of the ancient amphibian

The presence of teeth and other modern features of this prehistoric species can help researchers to better understand the evolutionary transition amphibians went through to get their unique features, such as teeth, today. A June 2021 study found that some species of frogs have lost and again evolved teeth several times throughout their lineages.

“This work is significant because it provides yet one more distinct early distant relative of our modern amphibians,” said David Blackburn, a coauthor of that 2021 study and a curator of amphibians and reptiles at the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida, via email.

“The last 20 to 30 years has seen many new species discovered and described of these distant relatives, and each discovery tends to reshape our knowledge of the evolutionary tree,” Blackburn added.

But Kermitops had many features distinct from its modern relatives. The critter’s robust skull had additional bones and elements that have likely disappeared with evolution, and its elongated snout paired with a short region of the skull behind the eyes was unique to the species, most likely serving to aid in catching insects.

The fossil’s features, a mix of modern and prehistoric traits, reinforces previous suggestions that amphibians’ evolution was complex, said Marc Jones, a curator of fossil reptiles at the Natural History Museum London.

“It further adds to the diversity of Early Permian animals that are likely the evolutionary cousins of modern amphibians. It highlights the need for more fossils from the Late Permian,” Jones said via email, adding he appreciated the amphibian’s name. “It’s not a frog but then technically neither is Kermit. He has five fingers and a lizard frill.”

The preservation of small fossils

The early fossil record for lissamphibians is considered to be fragmentary, according to a news release from the Smithsonian Institution, and is largely due to the creatures’ small size and delicate bone composition, which make the fossils difficult to preserve and find later, So said.

“What we see today is but a small percentage of all the things that were living in Earth’s history,” So added. “And one of the conditions that significantly improves fossil preservation is their size, because if it’s larger, it’s going to be more resistant to some of the erosional forces that we experience such as wind erosion and water erosion.”

What’s more, while prehistoric species are typically thought to be large, Kermitops could help to fill in the gap of amphibian evolution, explaining how some of today’s critters got their small size.

The skull of Kermitops is of similar size to the skull of another well-known Early Permian amphibian, Gerobatrachus, which had a head about an inch in length (2.5 centimeters). But many frogs today have bodies shorter than that length, Blackburn said.

“You might wonder, ‘Were there really no very tiny vertebrates in the past, similar in size to miniature species today?’ My bet is that yes, they existed, but our ability to find them in the fossil record is very difficult,” Blackburn added.

So said they hoped the species’ name would draw attention to the notable discoveries that paleontologists make through studying museum collections of prehistoric fossils — including those less imposing than dinosaurs.

“We wanted to name it Kermitops because we wanted to bring attention to this unique fossil that’s really small, that most people would not notice if you were to put it next to a Tyrannosaurus in the gallery,” So said.