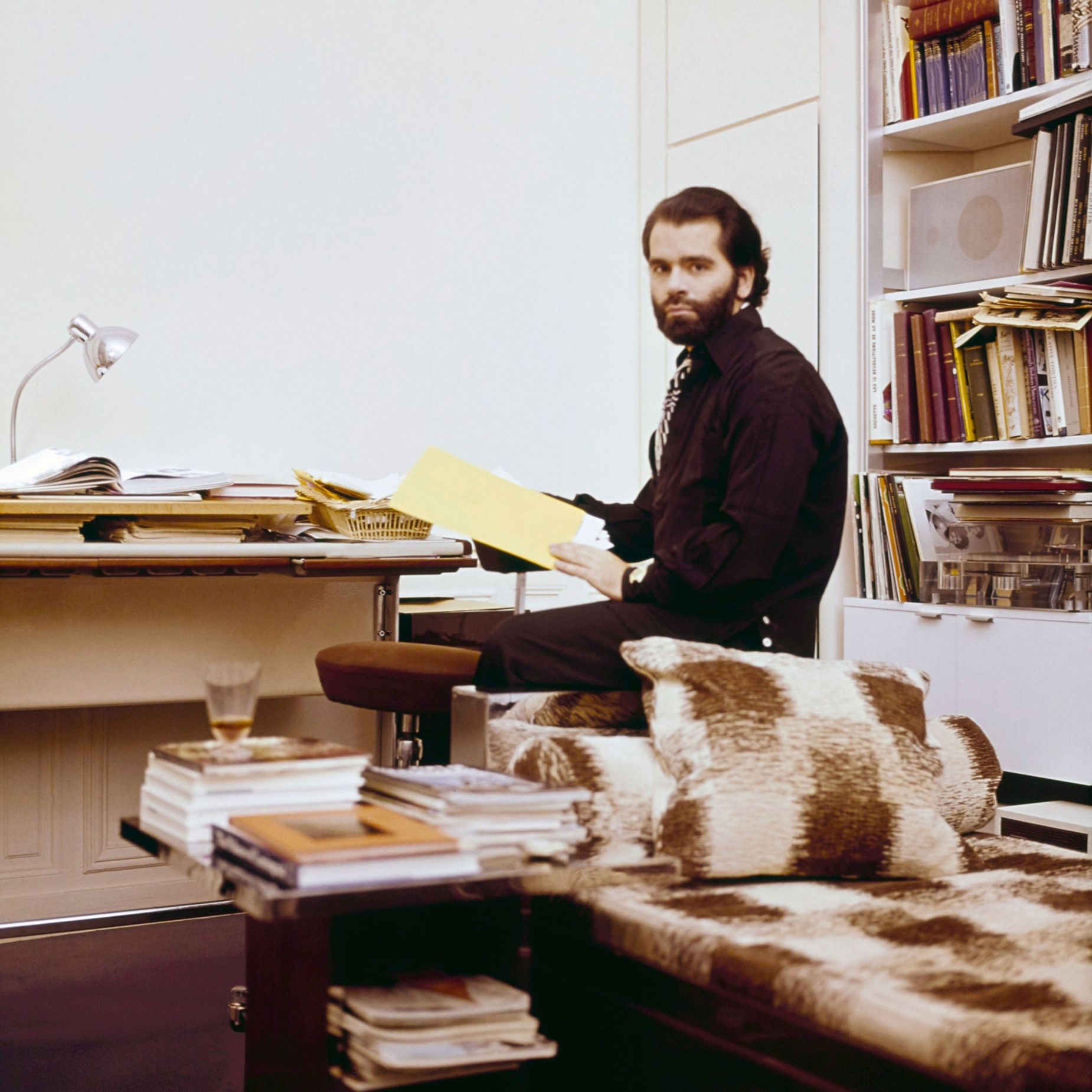

Fashion writer Patrick Mauriès first met Karl Lagerfeld in 1981, after he quoted the fashion designer in a short book he had written about contemporary fashion and culture. Although Lagerfeld had by that time already designed for the luxury houses Chloé and Fendi, he was not the iconic figure he would become later in life, particularly after he joined Chanel as creative director in 1983 — a role he held until his death in 2019. As his star rose, he and Mauriès remained good friends, with the writer enjoying rare glimpses into parts of Lagerfeld’s private life and way of living at his many lavish properties over the years.

“Everything was absolute luxury. Even when you went for a small lunch with him, the napkins were embroidered,” said Mauriès, recalling how Lagerfeld was one of the first people he knew to use Diptyque candles at home — but never just one of them, of course. “There would be 20 candles in the staircase leading to the dining room, and so it was a very high luxury feeling.”

The full extent of this tirelessly-curated “high luxury” is revealed in the new book “Karl Lagerfeld: A Life in Houses,” with an introduction by Mauriès and accompanying texts about each home by Marie Kalt, a former editor of “Architectural Digest France.” Featuring rarely-seen images of 13 of Lagerfeld’s properties in Europe — spanning Paris, Monte Carlo, Rome, Hamburg and more — the book reveals a lesser-known side to the designer, and provides insight into his sense of style when it came to interior design.

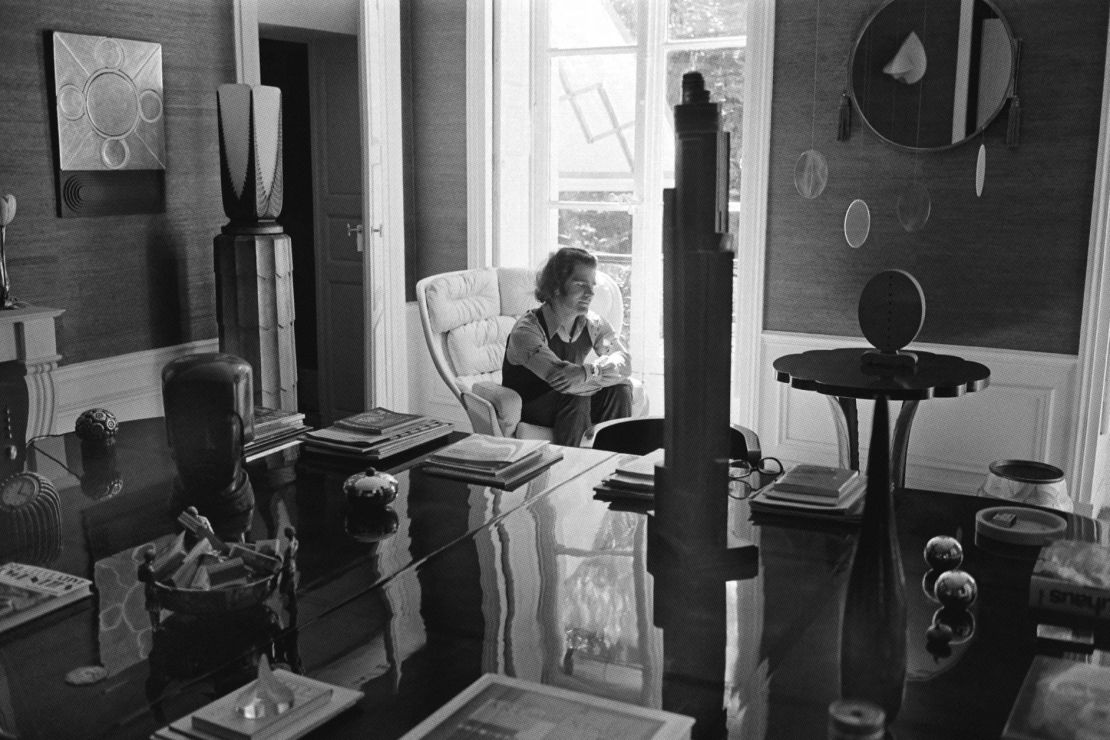

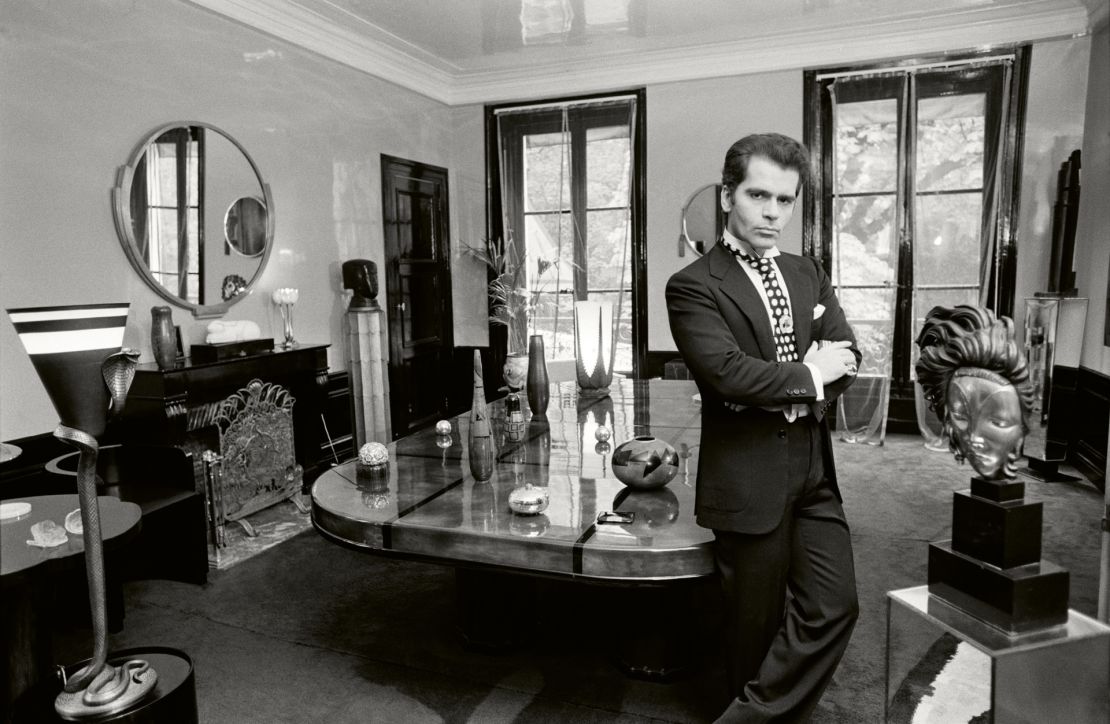

Each property was decorated in a different, distinctive way. Lagerfeld’s early Parisian home on the Rue de l’Université — an apartment on the second floor of an 18th-century mansion he shared with his mother in the 1960s and ‘70s — was filled with Art Deco furniture and homeware, from the sofas to the cocktail glasses.

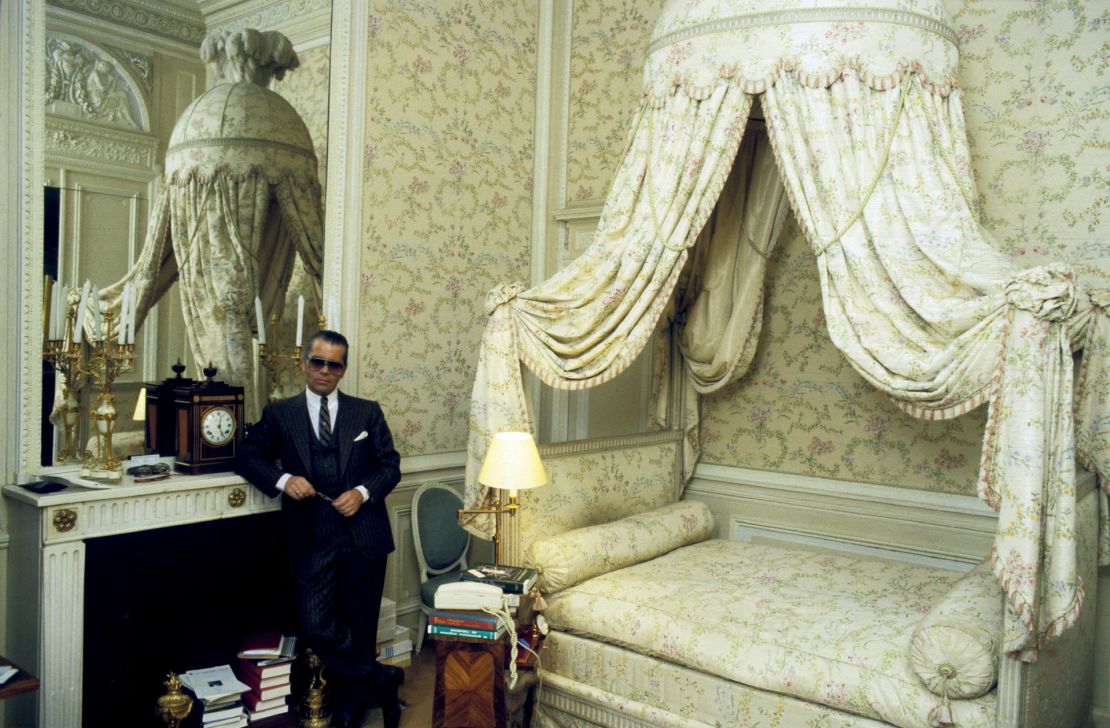

In 1977, Lagerfeld moved into the 18th-century Hôtel Pozzo di Borgo in Paris, with his residence — or residences, rather, as he moved at various points between different parts of the building — evoking the grandeur and spirit of the Age of Enlightenment with ornate tapestries and gilded detailing in many of the rooms. “He was playing all the time with the spirit of the place,” said Mauriès, adding that some of the only common threads in Lagerfeld’s interiors were nods to his German heritage.

In the Monte Carlo residence he bought in the 1980s, Lagerfeld was drawn to the Memphis Group design school, a collective of designers founded by Italian architect Ettore Sottsass that made use of bold colors, geometry and playfulness. Lagerfeld’s residence in his German hometown of Hamburg, named Vila Jako after his long-term companion Jacques de Bascher, was bought in the early 1990s; Lagerfeld then filled its interiors with objects including vases from the Swedish Grace design movement, which was a bridge between Art Nouveau and Modernism.

“It was always changing from one atmosphere to another, from antiquarian interiors to ultra-modern ones,” said Mauriès of Lagerfeld’s design aesthetic, having visited many of his properties over the years, particularly those in Paris. “He’s a singularity in that there is no unity in his type of decoration.”

And, as Mauriès explained, while Lagerfeld derived inspiration from the past, a sense of change and forward momentum was an inherent part of his creative practice. “What was essential for him was to live in the present tense or the present times. Once he thought something was a bit outdated or not of the moment, he discarded it and put it in storage,” said Mauriès. “He was always moving, he couldn’t imagine himself stuck in a period or style.”

In fact, Mauriès compared Lagerfeld’s approach to decorating each home as almost like designing a theater set, as the designer became completely immersed in the details and minutiae of one space at a time. “And then when it was done, he lost a bit of interest, and went on to create another one.”

In a way, this process of reinvention was also an embodiment of Lagerfeld’s fashion design, from one season to the next, and the evolution of his own image and sense of personal style.

As Lagerfeld became more of a public figure in the 1990s and 2000s, he increasingly sought homes that could act as retreats, said Mauriès. “It was something he needed to refocus and recreate himself… He needed these lairs in which to work.”

In keeping with Lagerfeld’s constant need for change, there is little left of the homes and interiors featured in the book. The designer sold many of the properties while he was still alive, and dispersed or bequeathed items he had collected in various ways, including by auction. A sale at Sotheby’s in 1991 saw Lagerfeld’s collection of 133 Memphis Group items go under the hammer, with a dressing table and matching stool designed by American postmodernist architect Michael Graves reaching 150,000 francs (then about $26,000, or around $59,000 in today’s money). A posthumous auction of objects from Lagerfeld’s estate, including his sketches, clothing and furniture, meanwhile, consisted of 1,200 lots assembled from five of his residences in and around Paris and Monaco.

Only one place that Lagerfeld called home has been preserved as it was when he lived there: the 7L bookshop and photo studio that he set up in 1999 in the Rue de Lille in Paris. The property was acquired by Chanel in 2001, and today acts as an homage to the designer. In his lifetime, Lagerfeld was known for his love of books, amassing huge collections and creating libraries in his residences. Today, the bookshop hosts regular public events and offers a library curation service for bibliophiles looking to build their own reading rooms at home.

“Everything disappeared — it’s a strange destiny,” said Mauriès. “But that follows his way of living. He was not interested in keeping memories or having these really private and intimate places preserved.”

Indeed, Lagerfeld’s own words quoted in the book outline this philosophy: “The most beautiful house is always the next one.”