Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

In Rembrandt’s enormous 17th-century masterpiece “The Night Watch,” a troupe of Dutch civilian soldiers gathers in a darkened room and prepares to march out to defend their city. Rembrandt, a master of light and shadow, strategically illuminated his subjects’ expressive hands and faces, while dimness hid the room’s details and obscured many of the guardsmen’s bodies.

That wasn’t all that the famous painting was hiding, researchers recently found.

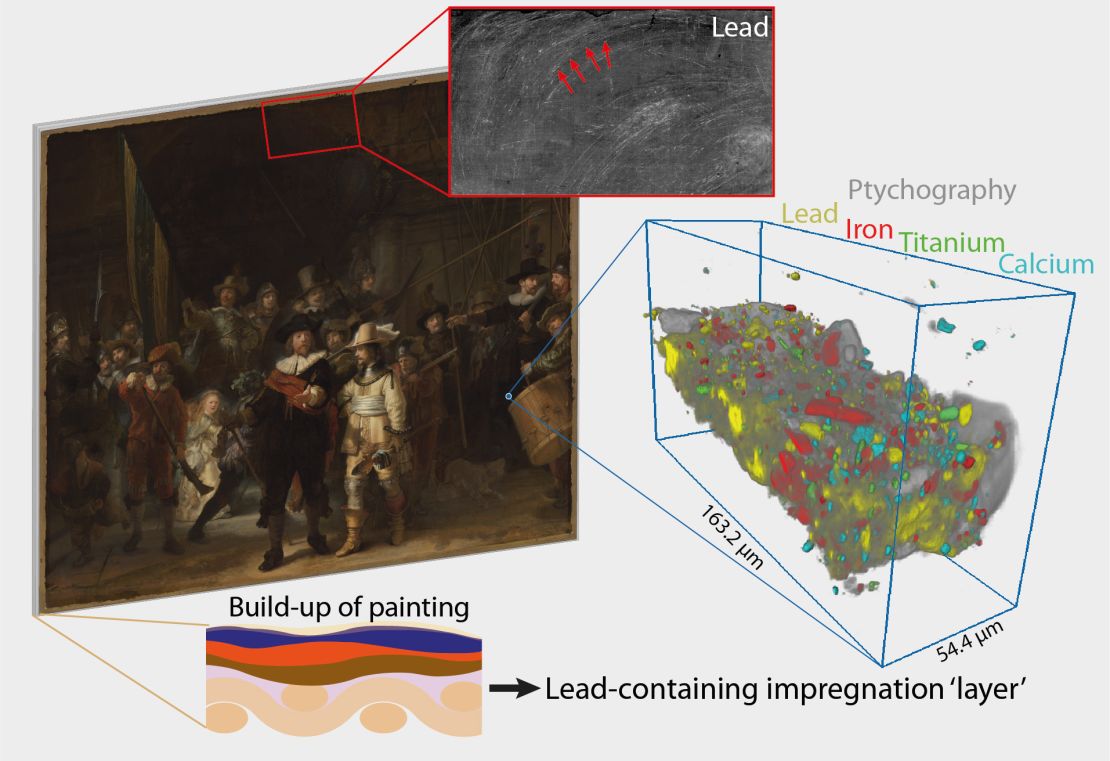

When conservators used X-rays to peer below the varnish and paint of “The Night Watch,” they discovered something unexpected under its surface: a layer that was full of lead.

This was the first evaluation in the painting’s 400-year history that combined X-rays with spectroscopy of a paint sample and 3D digital reconstructions, and it revealed a lead-rich layer that had never been seen before in Rembrandt’s works, researchers reported Friday in the journal Science Advances.

Rembrandt and his artist contemporaries typically started a painting by first coating the canvas with a stiffening layer of glue, then adding a base coat of underlying pigment, known as a ground layer, to prime the canvas.

But there was no glue layer in “The Night Watch.” The lead-saturated layer may have been used instead because it could better protect the canvas, the study authors suggested.

When the painting was completed in 1642, it was hung in Amsterdam’s Kloveniersdoelen — a musketeers’ shooting range — on a wall facing a row of windows, where it would have been vulnerable to damage from moisture.

Rembrandt may have gotten the idea to reinforce his canvas with lead from a publication about the chemistry of painting, penned around that time by a physician from Geneva named Théodore de Mayern, said lead study author Fréderique Broers, a research scientist of microscopy at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, where “The Night Watch” is on display.

In his writings, Mayern mentioned observing a painting that had been prepped with glue, and the paint and glue layers had separated after the artwork hung for several years on a damp wall. In such circumstances, Mayern wrote, a canvas required a foundational layer of lead-rich oil. The researchers suspected that Rembrandt opted to work with lead “as it has more drying properties in comparison to the normal glue layer for preparing the canvas,” Broers told CNN.

Whether the inspiration came from Mayern or discussion among painters, Rembrandt likely embraced the uncommon technique as a promising safeguard for a painting that he knew would be displayed in a humid spot, Broers said. The new findings suggest that Rembrandt was open to exploring unconventional methods that deviated from his standard practices, in order to execute his unique artistic vision.

Operation Night Watch

The researchers’ detective work was part of a conservation and analysis project called Operation Night Watch, which the Rijksmuseum launched in 2019. The painting’s real name — “Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq” — became “The Night Watch” in the 18th century, in part due to its heavy varnish coating and the passage of time. As the varnish yellowed and darkened from years of dirt, viewers mistakenly came to believe that the scene took place at night.

Layers of varnish were removed when the painting was cleaned in the 1940s, lifting much of the darkness. But there was still much work to be done restoring and analyzing the artwork. Operation Night Watch is “the largest and most wide-ranging research and conservation project in the history of Rembrandt’s masterpiece,” with a goal of delving deeper into Rembrandt’s process than ever before and preserving the painting for many decades to come, according to the Rijksmuseum’s website.

For the study, the researchers combined data from large-scale scans of the painting using X-ray fluorescence and powder diffraction, as well as reflective imaging spectroscopy. These novel techniques created visualizations of chemical elements and molecules, revealed their distribution, and showed where crystalline structures formed.

A tiny paint sample measuring just 0.002 inches (55 micrometers) wide and 0.006 (160 micrometers) long was removed from the painting, scanned and then digitally modeled in 3D — a new approach that shed light on how the painting was assembled, Broers said.

“Often you see a painting as a 2D object, but actually, it’s really a 3D object because we have all of these paint layers,” she explained. Research on 3D objects requires a 3D perspective, “to really understand the size of the particles and how the different pigment particles are related to each other.”

A mystery laid to rest

For decades, experts had been mystified by the appearance throughout the painting of tiny “pimples” of lead crystals that rose to the surface seemingly out of nowhere. Lead is commonly found in the pigment lead white, but there was little bright white in “The Night Watch.”

The tiny lead flecks were even popping up in the darkest regions of the painting, further compounding the enigma, Broers said. With the identification of a lead-rich layer coating the canvas, that mystery has finally been laid to rest.

“It’s a really big puzzle piece to understand the current condition of the paint,” she said.

Another important discovery made during prior investigations was the composition of the ground layer, which is located above the lead one and made of quartz and clay. It was the earliest evidence of Rembrandt using that mixture, which he continued to use (though not exclusively) for the rest of his career.

Previously, Rembrandt had primed his canvasses with a double ground layer: one of red earth and then another of white pigment. But “The Night Watch” was much larger than any of his other works, measuring 12.5 feet (3.795 meters) high and 14.9 feet (4.535 meters) long. A single ground layer would have been lighter, more flexible and cheaper than his usual double layer, according to the study.

The successes of Operation Night Watch come from a multi-pronged approach to its preservation and protection, Broers added. Data from X-ray scans was evaluated alongside details uncovered by cleaning and conservation experts. Curatorial interpretation provided a historical backdrop for the chemical components uncovered in the paint and primer layers. Together, these diverse disciplines usher “The Night Watch” into the modern age for generations of art-lovers to come.

“We really needed all of the expertise from the whole team of Operation Night Watch to bring it into context,” Broers said.

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American and How It Works magazine.