The Hippocratic oath serves as a mission statement for physicians, articulating principles that guide their work. Its tenets include beneficence, nonmaleficence and confidentiality, but they are often summed up by one simple phrase: “Do no harm.”

It may seem unthinkable, then, for a doctor, guided by this oath, to knowingly put a person’s life at risk. But history has proven that it can happen — and on a grand scale.

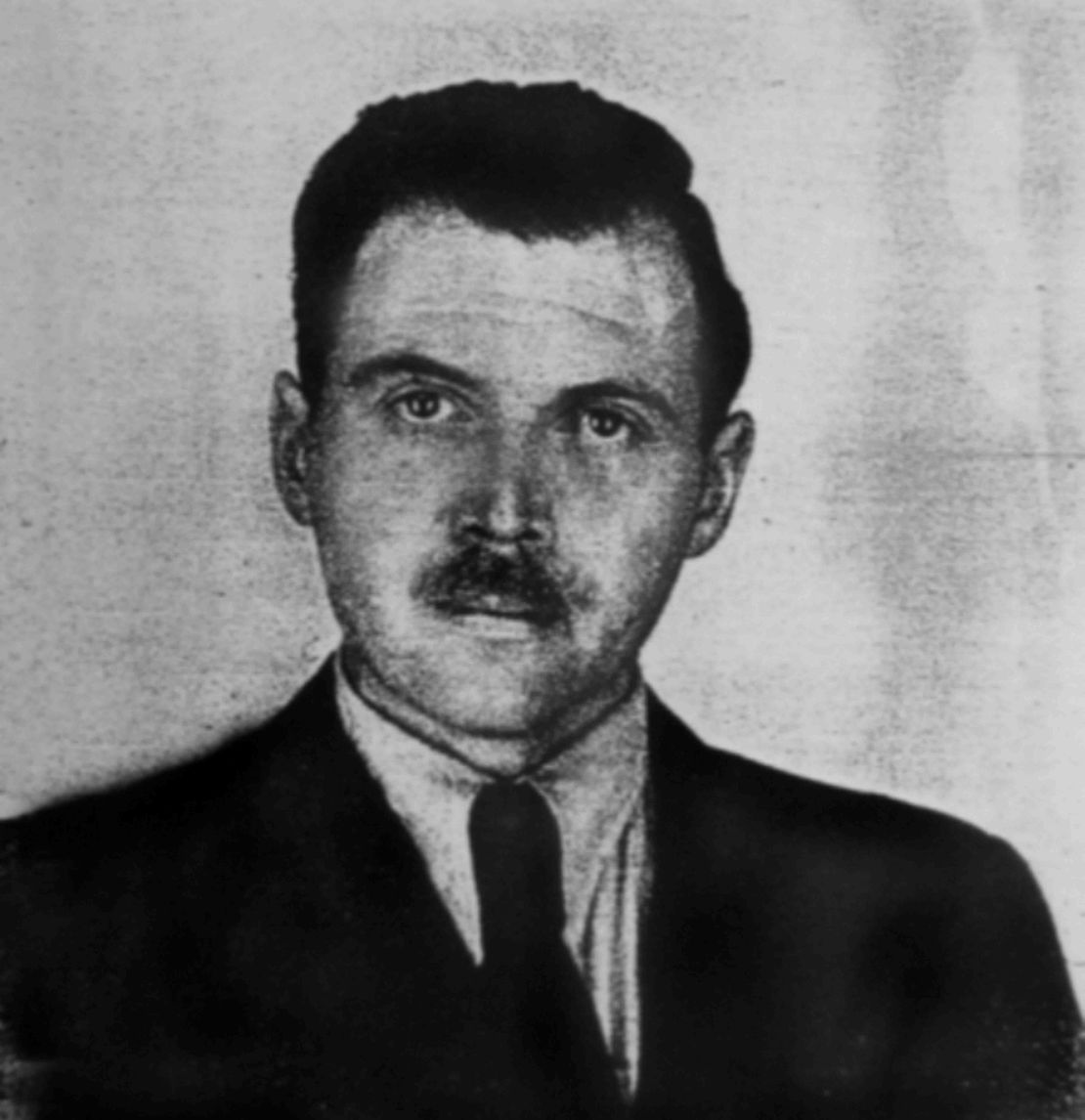

In Nazi Germany, many physicians who supported the Nazi ideology carried out dangerous and torturous medical experiments on concentration camp prisoners. Drugs and medical treatments were tested on them before being used on military personnel. Sterilization experiments were conducted to identify the most efficient way to control the population of Jews, Roma and other groups. And, most famously, Dr. Josef Mengele carried out cruel experiments on twins.

Dr. Robert Klitzman, director of the masters in bioethics program at Columbia University and author of The Ethics Police?: The Struggle to Make Human Research Safe, says that to make sense of the cognitive dissonance required for a doctor to act with such malice, we must recognize that people have a tendency to rationalize their behaviors. He spoke with CNN Opinion recently about a growing call among physicians and medical institutions around the world to learn from history so we don’t repeat it.

Indeed, as retired physician Raul Artal, who was born in a concentration camp, wrote in a 2016 article published by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC): “Nazi physicians claimed the moral high ground by transforming the Hippocratic Oath from a doctor-patient relationship to a state-Völkskorper—or nation’s body—relationship. They justified the sterilization or elimination of ‘lives not worth living’ as a merciful preventive measure, simultaneously ending the suffering of the genetically inferior and preventing transmission of their presumably hereditary harmful traits.”

After World War II, nearly two dozen physicians, scientists and public health officials were among the Nazi leaders who were tried for their role in the holocaust at the Nuremberg Trials. This represented a moment of reckoning for the global medical community. How could medical crimes against humanity be prevented from ever happening again? The answer, the court decided, was to create 10 directives for human subjects research: the Nuremberg Code.

We still rely on this code today, and have created additional regulations and ethics bodies to review the conditions of medical research. Nonetheless, experts have warned that we mustn’t be complacent.

“The history of medicine during Nazism and the Holocaust can support such critical reflection at all stages of the professional life cycle. It can help us recognize patterns to avoid or aspire to, and thus support us in the development of our own stories of ethically responsible health care,” wrote doctors Hedy Wald and Sabine Hildebrandt in an editorial published by AAMC in 2022.

The Lancet Commission on Medicine, Nazism, and the Holocaust argued in a lengthy report, “The core values and ethics of health care are fragile and need to be protected.” The commission has called for health care education to include a history-informed framework “to emphasise the unique opportunities and responsibilities of health professionals in the elimination of antisemitism and racism and the protection of vulnerable populations against stigmatisation and discrimination.”

For Klitzman, these are much-needed calls to action. “[The Holocaust] reminds us how fragile our ethical and moral standards can be,” he says, noting that one important way for us to keep our values in check is to examine history — study the Holocaust and other instances of moral failing in medicine — and for medical professionals to be vigilant about checking their own biases.

Learning from the past is not a radical idea. But, as so many experts are reminding us, if done earnestly, it could have a radical effect on the future.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

CNN: Why do you think it’s important that we examine the atrocities that health professionals committed during the Holocaust?

Robert Klitzman: Examining these issues is important for several reasons. Paraphrasing from the philosopher George Santayana: Those who do not learn from history are destined to repeat it.

A major problem is that physicians in the Nazi era, who were trained to follow the Hippocratic Oath and to abide by high moral standards, abandoned those principals under political and social pressures. The reason that’s important is that it reminds us how fragile our ethical and moral standards can be. And, unfortunately, there have been times — and there are still times — when physicians have not followed the ethical and moral standards they should.

For instance, there is still racism in healthcare. If you look at outcomes during the Covid-19 pandemic, people of color were at higher risk of dying from Covid. The evidence suggests that it’s not due to something biological, but rather access to care and, in some cases, the treatment they received.

So, we know that biases, racism, antisemitism, etc., can creep into health care. We’ve seen repeated examples of it since the Holocaust. Physicians need to be aware of that history so they can avoid repeating it.

CNN: How can we use that history to inform our modern bioethical principles?

Klitzman: What the Nazis did made us more aware of the importance of bioethical principles and led to the development of better guidelines to try to ensure that doctors follow the ethical guidelines they should.

The Hippocratic Oath that doctors take doesn’t cover research ethics. It does not touch on risk-benefit ratios for research participants – the assessment of the potential risks and the potential benefits for the participant. It doesn’t touch on informed consent – the idea that participants consent to being part of the study, with full information of what it means for them. It doesn’t touch on equity – the idea that you do not want to disproportionately burden or benefit any particular groups through the research.

After the horrific Nazi experiments, it was overwhelmingly clear that the medical experimentation performed by the Nazis needed a response and so, during the Nuremberg Tribunals a set of guidelines was developed for medical research. So, the events of the Holocaust have already informed our bioethics, but it’s important to continue examining this history as the world evolves and our medical ethical principles need to evolve along with it.

CNN: The Lancet Commission, among other institutions, has voiced concerns that medical curricula don’t sufficiently teach about Nazism, the Holocaust and ethical failures throughout medical history. What do you feel is the most appropriate way for medical education to impress upon doctors that the need to be ethically vigilant is an inextricable part of practicing medicine?

Klitzman: I think that the curriculum in many medical schools would benefit from providing more information on the Holocaust and Nazi experiments, and other violations of research ethics that have occurred. This heightened awareness could change the ways medical students appreciate medical ethics because bioethical principles can seem very straightforward, uncontroversial and easy to follow, and, therefore, easy to dismiss as not requiring particular attention.

However, the Nazis and the Holocaust vividly and dramatically illustrate how physicians can come to deviate from ethical standards and justify to themselves egregious ethical failures – how “blind” doctors can become when they face conflicting pressures and goals.

CNN: I’d like to talk about the Hippocratic Oath. Reciting it may seem like a ceremonial part of becoming a doctor, but the message it carries underlies a doctor’s fundamental mission. Can you explain to me what the Hippocratic Oath says and why is it so important in the context of bioethics?

Klitzman: The Hippocratic Oath is a statement that emphasizes the fact that practicing medicine is a moral enterprise.

Medicine involves people putting their bodies and private information in your hands as a doctor. If someone says, “‘I’ve had four miscarriages,” or “I am an addict,” or “I’m gay,” they’re trusting you that their body and their privacy are safe. There is an implicit social contract. And because of this, society has decided not to overly regulate doctors with laws. Instead, doctors have a great deal of discretion. And in return, doctors are committed to following a very high moral standard. In the West, parts of that standard are articulated in the Hippocratic Oath.

CNN: The idea of eugenics was key to the medical experimentation carried out by Dr. Mengele and other health professionals during the Holocaust. Can you explain what eugenics is and how it became a tool in the Holocaust?

Klitzman: Eugenics is the notion that you can improve the genes of individuals or society. It’s very much aligned with racism and prejudice.

Hitler’s idea was to “improve” the genes of the German people, which meant that if someone was disabled, gay, Jewish, etc., he wanted to get rid of them. I should make very clear that eugenics is completely warped and not based on anything scientific; in the case of the Nazis, it was used as a weapon against anyone Hitler’s regime deemed “inferior.”

Eugenics is not to be confused with public health; it’s one thing to want to improve the health of a country. But that’s extremely different than saying, “Let’s improve the genes of the country by getting rid of certain people.”

CNN: We’re now living in a time where technology like CRISPR, which allows for the editing of DNA, could make genetic engineering a feasible practice - essentially allowing us to tweak the genes of embryos. A key concern among experts is that the application of this technology could, once again, lead to eugenic practices. In fact, in 2018, twins were born that had been genetically modified as embryos, which some bioethicists called “ethically problematic.” What do you think needs to happen to prevent new technology like this from being used unethically?

Klitzman: There are several ways gene editing could lead to eugenics, with parents who can afford it paying to create children with the most socially desirable traits. But there are also more complicated scenarios that could arise.

Let’s take the example of using gene editing technology to remove from an embryo genes associated with various diseases – whether cancer or Alzheimer’s. This may, on the surface, seem like a good thing. But, in fact, this raises a number of concerns because wealthy people could pay to remove these genes, while poor people likely could not. This could lead to more disparities in society; certain diseases, which now unfortunately affect many people, whether rich or poor, could increasingly become diseases of the poor. And, of course, that’s a problem because then there would likely be fewer resources for people with these conditions, less money devoted to research, etc.

One of the bioethical principles, as I said, is to avoid unfairly burdening or benefiting one group or another. Eugenics threatens that bioethical principle of social justice. So, we need to be very careful.

CNN: The Holocaust is the most notorious example of medical experimentation — and perhaps for Americans it’s easy to assume that what happened in Nazi Germany could never happen in the US. But the US, too, has engaged in unethical medical experimentation. One of the most well-known instances was the Tuskegee Study. Can you tell me about that study and how the lack of informed consent created unethical experimental conditions?

Klitzman: The Tuskegee study was one of the most egregious examples of medical experimentation, with grossly inadequate informed consent. Starting before World War II, The Tuskegee Institute and the US Public Health Service, wanted to understand the natural course of a syphilis infection. So researchers decided to follow a group of poor, Black sharecroppers in the South, many of whom were semi-literate, and decided to see how untreated syphilis affected their bodies over time.

One of the problems with the study was that, after World War II, when penicillin was discovered to be the definitive cure for syphilis, the researchers decided not to offer penicillin to the study subjects because that would have inevitably ended the experiment. They decided that the value of the experiment was worth the suffering of and risk to the subjects.

The Tuskegee study went on for decades until the 1970s, when a story about it came out in the press and led to an advisory panel reviewing the study. This shows us that, even after the Holocaust, here in the US there were still instances of unethical medical research.

As a result of the Tuskegee study, the National Research Act was passed in 1974, which was key in establishing modern research ethics as we know them today. Since then, we’ve also developed research ethics committees or Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), to help ensure that research is carried out ethically.

But even with these formalized research ethical standards, it is often a fight to make sure that guidelines are followed.

CNN: Trust in science and scientists is on the decline, and we’ve seen this distrust lead to dangerous trends in vaccine hesitancy and pushback on public health guidance. For instance, when Covid-19 vaccines initially became available, the mistrust of health professionals among Black Americans in Tuskegee, Alabama, the place where the Tuskegee study was carried out, likely contributed to the fact that less than 6% of vaccine doses initially went to Black Americans while over 60% went to White Americans. So, how do we address this lack of trust, while also acknowledging that it is valid and is steeped in history?

Klitzman: When it comes to combating distrust in the public health system we have to ask: What is the message? Who’s giving it to whom? And how is it being given?

If we have White doctors telling everyone, “You need to do this, you need to do that,” and people who don’t have trust in the system aren’t given much choice in the matter, that’s problematic.

Trust is easily broken and once broken, hard to reestablish, but having the message come from people who understand that distrust, and who are willing to listen to what people’s concerns are, is important. And, of course, the first step is acknowledging the fact that bad things have been done in the past that have understandably led to distrust.