Editor’s Note: Jill Filipovic is a journalist based in New York and author of the book “OK Boomer, Let’s Talk: How My Generation Got Left Behind.” Follow her on Twitter. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely her own. View more opinion on CNN.

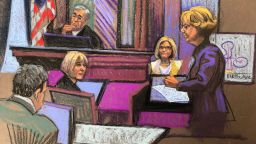

Celebrity couple Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis are in hot water this week after character letters they wrote for actor Danny Masterson, their co-star on “That ‘70s Show,” were made public. Masterson was facing a judge for sentencing after he was convicted of raping two women in 2003. Kutcher and Kunis were among several high-profile friends of Masterson who gave character references at Masterson’s family’s request. Masterson ended up being sentenced Thursday to 30 years to life in prison.

The crimes for which Masterson was convicted are awful and shocking: The two women he was convicted of raping said that Masterson gave them a drink which made them feel disoriented and nauseous, and then he raped them, according to the LA Times’ reporting on the case. One said he assaulted her so violently that she vomited. Another said he held a gun while he raped her, and put a pillow over her face.

These assaults occurred in the early 2000s, and the victims were members of the Church of Scientology; Masterson was as well.

The Kutcher and Kunis letters weren’t very effective in convincing the judge to offer forbearance. Masterson, who has long denied committing the rapes he was convicted of (and others he wasn’t tried for), was sentenced to 30 years to life in prison. His lawyers say that the jury got it wrong, and that Masterson will appeal the conviction.

The letters were, however, highly effective in engendering a massive backlash. Kutcher and Kunis ostensibly did not expect the letters to become public, and now that they have, the couple is apologizing. The letters, Kutcher said in a video posted to Instagram, “were intended for the judge to read and not to undermine the testimony of the victims or retraumatize them in any way. We would never want to do that, and we’re sorry if that has taken place.”

Kunis said, “We support victims. We have done this historically through our work and will continue to do so in the future.”

Particularly galling for critics of their apology seems to be the fact that Kutcher has positioned himself as an anti-rape activist, starting an organization to combat child sex trafficking and testifying before Congress in support of efforts to combat trafficking and sexual abuse.

Kutcher’s acts do seem solidly hypocritical: He is widely praised for his public fight against sexual abuse, and then in private he advocates for a convicted sexual abuser. No wonder people are angry.

But real life, of course, is complicated, and human beings can be both virtuous and hypocritical, kind and cruel. Kutcher and Kunis can be dedicated to their philanthropic work and genuinely care about sexual violence, while also caring about a friend’s future – even after knowing that that friend had committed acts of egregious sexual violence. This capacity for nuance is a human strength; we would perhaps all be better off if we didn’t render the world in black and white.

It is possible to both believe that someone committed a grievous wrong, and also believe that they are a good person deserving of grace. The US justice system is notoriously punishing, and the US imposes longer prison sentences than that of many peer nations. We incarcerate an enormous number of people, and prisons do relatively little to rehabilitate offenders. There are many people who both care about justice for sexual violence victims and creating a justice system that is fairer, more merciful and more focused on repair than retribution.

In other words, writing a character letter to a judge in an effort to paint a fuller picture of a person convicted of a crime is not in and of itself a bad act, nor suggestive that the writer doesn’t care about crime victims.

The Kutcher and Kunis letters, though, do something different. Both letters — along with the many, many others written by Masterson’s friends, family members and professional contacts — emphasize his good character and his commitment to his family. But the Kutcher and Kunis letters also focus on Masterson’s opposition to drugs. “One of the most remarkable aspects of Danny’s character is his unwavering commitment to discouraging the use of drugs,” Kunis wrote. She emphasized that “His dedication to living a drug-free life” make him “an outstanding role model and friend.”

Kutcher wrote that he “attribute[s] not falling into the typical Hollywood life of drugs directly to Danny,” and that “anytime we were to meet someone or interact with someone who was on drugs, or did drugs, he made it clear that that wouldn’t be a good person to be friends with.” Masterson, Kutcher also wrote, once interfered on behalf of a girl who was being berated by a “belligerent man” in a pizza shop. “I can honestly say that no matter where we were, or who we were with, I never saw my friend be anything other than the guy I have described,” Kutcher wrote.

The effect is to cast doubt on the veracity of the women’s testimony. The victims, after all, claimed Masterson drugged them before raping them. While Kunis and Kutcher don’t come out and say that they don’t believe the victims, the implication is that the accusations are far enough out of character for Masterson that perhaps they aren’t true.

People can be many things at once: There are men in the world who are loving husbands, doting dads and upstanding friends, but who have also raped women. That a person has been benevolent may earn him some good will among those who experience his benevolence, but it does not mean that he is entitled to avoid consequences for the moments in which he is vicious.

A functional justice system should ask: What is the wrong here, and how severe is it, and how do we appropriately penalize the person who committed it and keep society safe from them? But a functional justice system should also seek more than just a maximal penalty. That Kunis and Kutcher asked a judge to consider Masterson as a whole person who has also done good in his life is not the problem.

The problem is that, in doing so, they seem to adopt the kind of good-or-bad, black-or-white thinking that causes so much damage. If they know Masterson as a good guy, the thinking seems to go, then he couldn’t have done this bad thing — or, at least, his goodness should blunt the reality of his crimes.

The problem isn’t that Kutcher and Kunis asked the judge to show mercy and compassion for Masterson. It’s that they offered so little of the same to his victims.