Stockton Rush, the CEO of OceanGate and one of five people on the submersible missing in the North Atlantic, has cultivated a reputation as a kind of modern-day Jacques Cousteau — a nature lover, adventurer and visionary.

Rush has approached his dream of deep-sea exploration with child-like verve and an antipathy toward regulations — a pattern that has come into sharp relief since Sunday night, when his vessel, the Titan, went missing.

“At some point, safety just is pure waste,” Stockton told journalist David Pogue in an interview last year. “I mean, if you just want to be safe, don’t get out of bed. Don’t get in your car. Don’t do anything.”

In another interview, Stockton boasted that he’d “broken some rules” in his career.

“I think it was General MacArthur who said you’re remembered for the rules you break,” Rush said in a video interview with Mexican YouTuber Alan Estrada last year. “And I’ve broken some rules to make this. I think I’ve broken them with logic and good engineering behind me.”

If the Titan is still intact, the US Coast Guard officials estimated Wednesday afternoon that the vessel may have less than a day’s worth of oxygen left.

The next frontier

Rush, who graduated from Princeton in 1984 with a degree in aerospace engineering, has said that he never really grew out of his childhood dream of wanting to be an astronaut, but his eyesight wasn’t good enough, according to an interview he gave Smithsonian Magazine in 2019.

After college, he moved to Seattle to work for the McDonnell Douglas Corporation as a flight test engineer on the F-15 program. He obtained an MBA from UC Berkeley in 1989, according to his company bio.

He nursed his space travel dream for years, imagining he would join a commercial flight as a tourist. But in 2004, he told Smithsonian, the dream shifted after Richard Branson launched the first commercial aircraft into space.

“I had this epiphany that this was not at all what I wanted to do,” Rush told the magazine. “I didn’t want to go up into space as a tourist. I wanted to be Captain Kirk on the Enterprise. I wanted to explore.”

Breaking rules

Rush founded OceanGate in 2009, with a stated mission of “increasing access to the deep ocean through innovation.”

As CEO, Rush oversees the Everett, Washington-based company’s “financial and engineering strategies” and provides a “vision for development” of crewed submersibles, according to his bio.

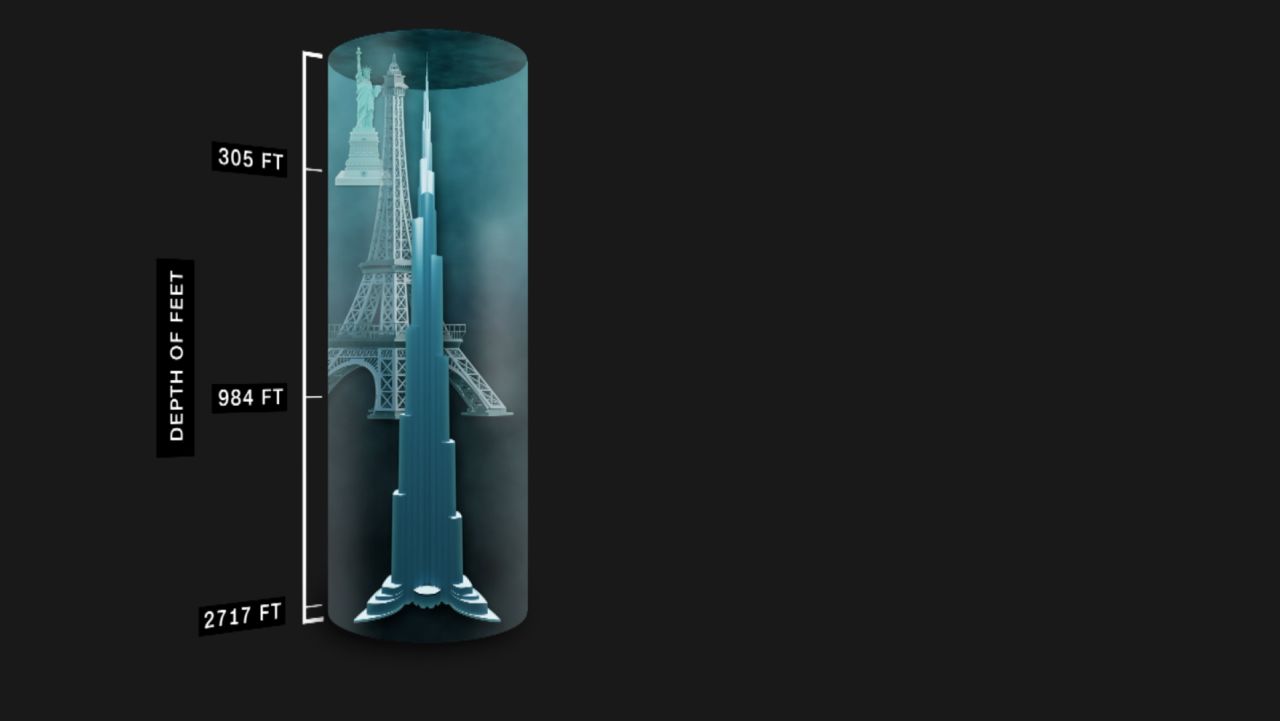

OceanGate currently operates three submersibles for conducting research, film production, and “exploration travel,” including tours of the site of the Titanic more than 13,000 feet below the ocean’s surface. A seat on that eight-day mission costs $250,000 per person.

Rush, who is 61, said he believes deeply that the sea, rather than the sky, offers humanity the best shot at survival when the Earth’s surface becomes uninhabitable.

“The future of mankind is underwater, it’s not on Mars,” he told Estrada. “We will have a base underwater … If we trash this planet, the best life boat for mankind is underwater.”

In his eagerness to explore, Rush has often appeared skeptical, if not dismissive, of regulations that might slow innovation.

The commercial sub industry is “obscenely safe” he told Smithsonian, “because they have all these regulations. But it also hasn’t innovated or grown — because they have all these regulations.”

Even within OceanGate, warnings from employees about safety appear to have been ignored or disregarded.

David Lochridge, OceanGate’s former director of marine operations, said in a court filing that he was wrongfully terminated in 2018 for raising concerns about the safety and testing of the Titan. The case was settled out of court, and the terms weren’t disclosed.

Another former employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, echoed Lochridge’s concerns. That employee said that as contractors and employees raised red flags, Rush became defensive and dodged questions in staff meetings.

OceanGate hasn’t responded to CNN’s request to comment.

NASA meets MacGyver

In recent days, as search teams have scoured the ocean for signs of the Titan and its crew, some aspects of the vessel’s design and on-board technology — such as the a videogame controller that the pilot uses to steer it — have raised eyebrows.

When CBS correspondent David Pogue took a trip on the Titan last year, he reported that communications broke down and the sub was lost at sea for more than two hours. He also asked Rush about what the vessel’s “MacGyvery” components — like the plastic PlayStation controller and LED lights that Rush bought from an RV retailer.

Rush pushed back against Pogue’s description in that interview, arguing that some elements could be less sophisticated as long as the key parts, like the pressure vessel, is sound. Rush said the pressure vessel had been built in coordination with Boeing, NASA and the University of Washington. Once you’re certain that the pressure vessel is not going to collapse on everybody, he said, “everything else can fail.”

“It doesn’t matter. Your thrusters can go. Your lights can go. All these things can fail. You’re still going to be safe. And so, that allows you to do what you call MacGyver stuff,” he said.

Pogue, in an interview with USA Today on Wednesday, recalled his impressions of the Titan. “Some of the ballasts are old, rusty construction pipes. There were certain things that looked like cut corners.”

‘The deep sick’

Extreme tourism is a lucrative, high-risk industry. And it’s only growing. With enough money, tourists can summit Everest, take a rocket to space, run multi-day ultramarathons catered by Michelin-rated chefs, or plumb the oceans depths that have largely been off-limits for humankind.

“What I’ve seen with the ultra-rich — money is no object when it comes to experiences,” said Nick D’Annunzio, the owner of public relations firm TARA, Ink. “They want something they they’ll never forget.”

In that respect, Rush shares something in common with his clients. In his interview with Smithsonian in 2019, he relayed his almost-spiritual attraction to the deep sea. He called it “the deep disease.”

“I went to 75 feet. I saw cool stuff. I went 100 feet and saw more cool stuff. And I was like, ‘Wow, what’s it gonna be like at the end of this thing?’”

— CNN’s Celina Tebor and Sam Delouya contributed to this article.