Editor’s Note: Mary Ziegler (@maryrziegler) is the Martin Luther King Professor of Law at UC Davis. She is the author of “Dollars for Life: The Antiabortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment” and “Roe: The History of a National Obsession.” The views expressed in this commentary are her own. Read more opinion on CNN.

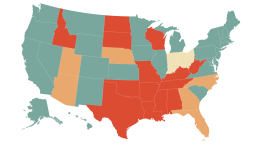

Nearly one year after the Supreme Court overruled Roe v. Wade, a new rule has solidified in American politics: no abortion access in the American South. And until recently, that rule had three increasingly visible exceptions — states which, unsurprisingly, became destinations for abortion seekers from across the region.

Florida saw the single greatest increase — reportedly 1,200 patients a month — after Dobbs. North Carolina, another receiving state, had seen a nearly 40% increase. After the South Carolina Supreme Court struck down that state’s abortion law in January, that state also saw a sharp increase in abortions, with roughly half of patients coming from out of state.

It seems that there won’t be exceptions to the rule for much longer. In North Carolina, Republicans recently overrode a veto by the state’s Democratic governor to pass a law that banned elective abortion at 12 weeks, prohibited medication abortion after 10 weeks and introduced a tough new waiting period that will make it harder for people traveling out of state to seek the procedure.

The South Carolina House once again passed a ban on abortion at six weeks, before many know they are pregnant, setting up a clash in the state Senate, where five female lawmakers had previously mounted a successful filibuster (the state Supreme Court had struck down a virtually identical law last year, but since the court’s composition changed, Republicans are betting that the new court will reverse course). And in Florida, Gov. Ron DeSantis, one of the likely frontrunners for the 2024 GOP nomination, signed into law another six-week ban with narrow exceptions (the state’s ultraconservative Supreme Court is expected to overturn existing precedent and allow the law to go into effect).

For those seeking abortions, or women experiencing life-threatening conditions that may not fit narrow exceptions to abortion bans, the closest option in the South may be Virginia, where Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin is pushing for a ban at 15 weeks, or Washington, DC.

With travel becoming prohibitively expensive and often complex, this region — known for the nation’s worst maternal mortality rates — will almost certainly be an even more dangerous place to be pregnant. For some, it comes as no surprise that the South would define itself as an anti-abortion region. But in reality its status as the center of anti-abortion America was not historically inevitable.

In its early years, the anti-abortion movement had the most influence in Catholic strongholds on the East Coast and Midwest, places that often elected Democrats as well as Republicans. Anti-abortion organizers, then as now, argued that the fetus was an independent person with rights, and that liberal abortion laws were unconstitutional, but they disagreed about how personhood should be enforced, with some calling for harsh punishment of providers and those who helped them, and others equally focused on laws that would make it easier for the economically marginalized to afford to carry pregnancies to term.

But when the anti-abortion movement aligned itself with the Republican Party in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it started moving south. White evangelical Protestants, who had once been uncomfortable with what they viewed as a Catholic movement, had spoken out about abortion before the late 1970s, but they became more publicly involved in the 1980s, heeding the advice of new organizations in the religious right like Concerned Women for America.

By the 1990s, conservative Christian law firms, many with ties to Christian Right organizations in the South, opened their doors or expanded considerably. The Alliance Defending Freedom, for example, the group litigating the current challenge to the abortion pill mifepristone, became a sort of mega-funder for anti-abortion litigation.

Jay Sekulow, an attorney who later represented former president Donald Trump in his impeachment hearings, led the American Center for Law and Justice, a well-funded group launched by televangelist Pat Robertson.

With new partners and members, the new anti-abortion movement was more comfortable framing its cause as a matter of faith, and more focused on harsh punishment for those perceived to have wronged the unborn child.

These messages reflected the new influence of Southern activists — the South, for example, has long had especially harsh criminal laws and high rates of incarceration, even in a nation with the highest rate of incarceration in the world. In turn, as different leaders took the helm, a focus on punishment resonated with the movement’s rank and file.

The anti-abortion movement is still complex, with a large Catholic cohort and members from other faith communities or with no faith commitments at all. A growing number of activists seek to require the government to provide limited aid, at least during pregnancy (the group Americans United for Life has launched an initiative to “make birth free,” while other anti-abortion lawmakers have voted for legislation offering paid family leave to some state employees).

Nevertheless, the epicenter of anti-abortion America remains the South, and as abortion access across the region disappears, that shift will have profound consequences. States with existing shortages in obstetricians (in South Carolina, for example, there was no practicing OB-GYN in 14 of 46 counties in August 2022) have seen a sharp drop in OB-GYN residency applicants — a 10.5% decrease in 2023 alone — that presages a possible future shortage in doctors. Other physicians are fleeing.

This exodus is not just an act of political resistance: It’s a reflection of doctors’ unwillingness to gamble their liberty on the interpretation of vaguely written laws backed up by harsh criminal sanctions. This physician shortage will almost certainly exacerbate what is already a dire situation for women in the South: six of the 10 highest maternal mortality rates are in Southern states.

And the pressures facing pregnant people are higher since Southern states combine harsh abortion bans and abysmal child welfare outcomes. According to the nonpartisan Annie Casey Foundation, eight of the 10 worst-performing states in terms of children’s well-being were found in the region.

Census data confirms this bleak picture of child welfare in the South: Three-quarters of Southern states had child poverty rates of at least 18%, compared to only one state in the Northeast and Midwest and two states in the West.

Southern states, which rarely have fully expanded Medicaid, pay low rates of minimum wage and rarely offer paid family leave, make it harder for women to raise the children they want while making it more dangerous to bring those children into the world.

Fights over reproduction will continue in the South: Work is under way on a ballot initiative that would restore abortion rights in Florida, and preliminary efforts on a similar strategy have started in Oklahoma.

Abortion may become a key election issue in state supreme court races. But for now, women seeking abortion or life-saving emergency care in a region that claims to be the most pro-life in the nation will often have to leave it. Whatever it means to be pro-life in America, it has to be more than that.