Editor’s Note: Megan W. Gerhardt, Ph.D is a professor of leadership at the Farmer School of Business at Miami University and author of the book “Gentelligence: The Revolutionary Approach to Leading an Intergenerational Workforce.” She speaks and consults globally on the power of age and generational diversity in the workplace. The views expressed here are the writer’s own. Read more opinion at CNN.

How old is too old to be president?

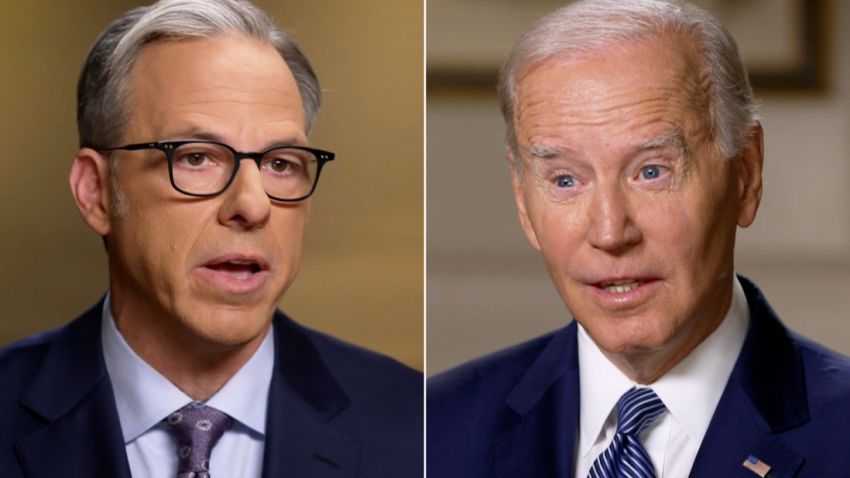

While the Constitution establishes a minimum age of 35 for anyone seeking the country’s highest office, there is no maximum. Some people appear to think there should be, as they question the idea of President Joe Biden – at 80 already the oldest Oval Office occupant – seeking a second term. (And, to a lesser extent, whether his leading Republican challenger, 76-year-old former president Donald Trump, is too long in the tooth as well.)

It turns out, however, that the ways age affects leadership are as much about perceptions as capabilities. And those perceptions are often wrong.

When we perceive someone as “young” or “old,” it triggers in each of us a set of assumptions and stereotypes – “age cues” – about what we can expect from that person. Research from the journal Leadership Quarterly finds these perceptions have deep roots: Since the early days of human evolution, youthful-looking leaders have been favored in times of change and exploration, when risk-taking is seen as necessary. Meanwhile, leaders who appear older have been preferred when people wanted to protect their existing resources, maintain stability and receive time-tested wisdom.

Evidence suggests that these kinds of age-based stereotypes in the workplace remain prevalent but very few are valid. We tend to associate older individuals with being less motivated, more resistant to change and less healthy. But a study of over 200,000 people found that none of those stereotypes are accurate.

Additional research done by London Business School professor Lynda Gratton has shown few differences between younger and older people in terms of their interest in learning new things, the energy they get from their work and their interest in staying active and healthy. She found that more people under the age of 45 said they were exhausted than those over 45, and those over 60 reported being the least fatigued.

When it comes to different types of intelligence, there are some variations among age groups – but no age has a monopoly on all of them. Younger people are stronger in so-called fluid intelligence, while older people instead rely upon what is known as crystallized intelligence.

Fluid intelligence focuses on the novel and the innovative: the ability to learn new things quickly and adapt in times of change. This type of intelligence was once thought to peak in our mid-20s, but some elements have been determined to peak into our 40s.

Crystalized intelligence, in contrast, develops throughout life and involves the ability to successfully use acquired skills and knowledge. It can be advantageous in tasks that require reasoning and resolving conflict. Recent research has found that this type of intelligence, often critical to successful leadership, continues to increase into our 70s.

Meanwhile, there is significant evidence that performance doesn’t necessarily decline with age. On the contrary, some aspects of job performance actually tend to increase as one gets older. For example, age has been found to be positively related to job productivity while having no negative relationship with task performance. Though decreases in cognitive ability can occur with age, they are often offset by the advantages of job experience and the strategies for navigating challenges that come with it.

Perhaps the most important age-related question for voters is whether there is any established relationship between age and effective leadership. The answer might seem less than satisfying but, broadly speaking, research has found mixed results. For example, as leader age increases, research has found productivity and peer evaluations of effectiveness both increase while supervisor ratings of effectiveness slightly decrease.

“At any given age, you’re getting better at some things, you’re getting worse at some other things, and you’re at a plateau at some other things. There’s probably not one age at which you’re peak on most things, much less all of them,” according to Joshua Hartshorne of MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences.

For White House aspirants specifically, studies of the job performance of our early US presidents have concluded that age was “totally irrelevant” in assessing their greatness, though admittedly it’s a small sample size.

In other words, there is no research declaring a certain number “too old,” as aging is an individual process. There might be a perceived age limit where voters will decide for themselves that a given candidate is too old for them, and it well might be based on whether they are seeking change or stability, not because of the candidate’s particular capabilities.

Get our free weekly newsletter

Regardless, Gratton reminds us, “As every one of us is faced with living and working longer, it is absolutely crucial that, whatever our age, we face up to and question unfounded assumptions and stereotypes about ourselves and about others.”

In other words, the argument over the age of our presidents may be getting old.