Editor’s Note: John Avlon is a CNN senior political analyst and anchor. He is the author of “Lincoln and the Fight for Peace.” The views expressed in this essay are his own. Read more opinion at CNN.

In museums of the future, there will be exhibits dedicated to the literary hero, artifacts from a time when novels were mass entertainment. These celebrated writers were the subject of long-form profiles and occasional tabloid scandals, treated as cerebral rock stars and voices of their generation.

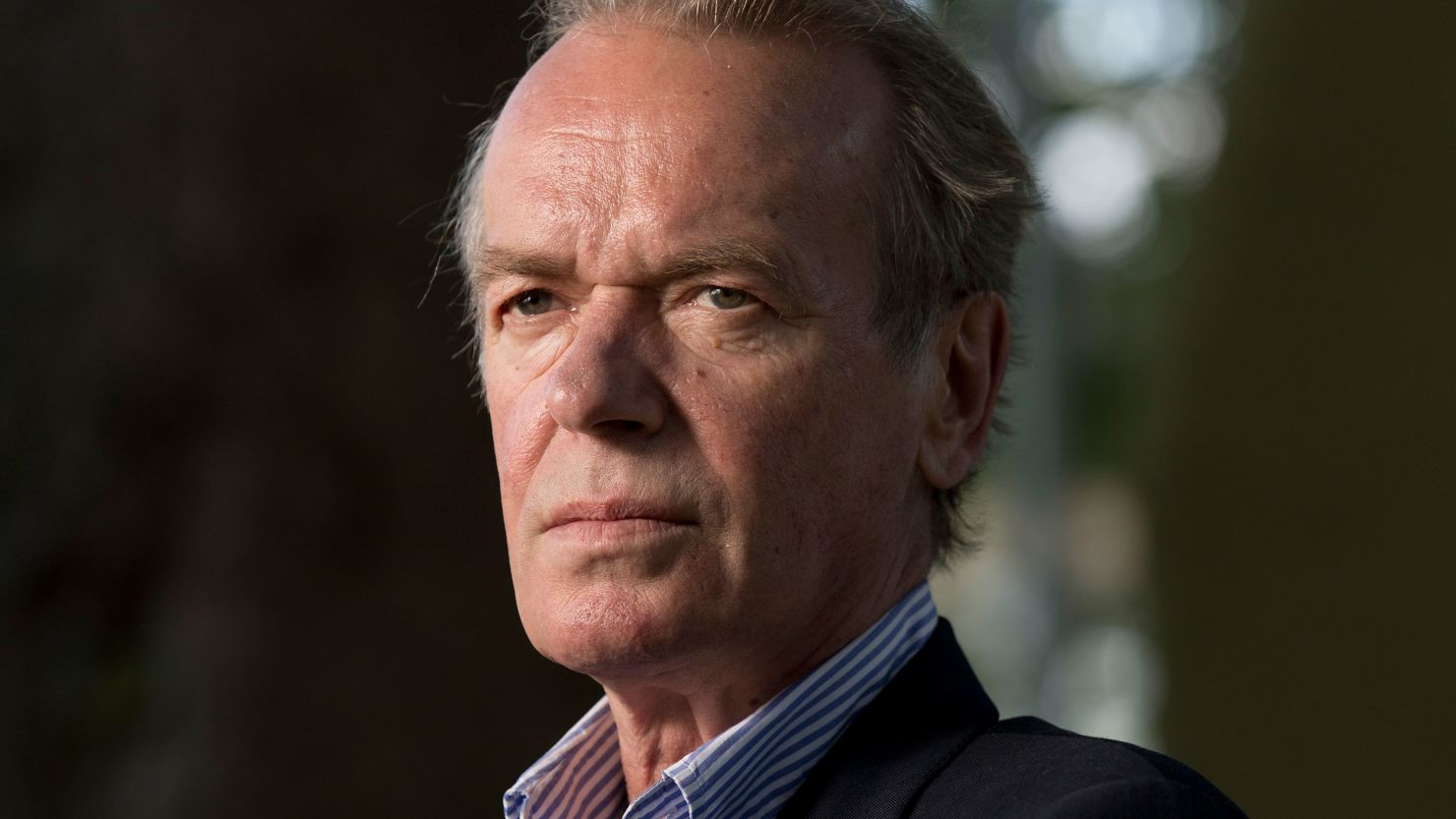

Martin Amis was one of our last literary heroes and his death at age 73 – from the esophageal cancer that also claimed the life of his best friend Christopher Hitchens – feels like a bookend to an era.

An impossibly cool and erudite observer, he chronicled transatlantic culture from the rise of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan through 9/11 to the whiplash between Barack Obama and Donald Trump in novels and essays. Everything he wrote was worth reading. He was not an overtly political writer – his markers were literary, from his father Kingsley Amis to Philip Larkin to Vladimir Nabokov and Saul Bellow, all of whom made frequent appearances in his work, with Martin acting as both witness and keeper of the flame.

His voice was unmistakable, the sound of all synapses firing with nicotine precision, diamond sharp and darkly funny. Gazing through shades, he could capture the sweep of skylines and dark alleys simultaneously. The opening paragraph from his novel “The Information” shows Amis in full plume:

“Cities at night, I feel, contain men who cry in their sleep and then say Nothing. It’s nothing. Just sad dreams. Or something like that…Swing low in your weep ship, with your tear scans and sob probes, and you would mark them. Women–and they can be wives, lovers, gaunt muses, fat nurses, obsessions, devourers, exes, nemeses–will wake and turn to these men and ask, with female need-to-know, ‘What is it?” And the men will say, ‘Nothing. No it isn’t anything really. Just sad dreams.’”

Beneath the virtuosic riffs, you could hear an author trying to defy the undertow of despair. It drove him from tragicomic stories of modern folly in pursuit of sex and money to the subjects of Hitler’s Holocaust and Stalin’s gulags, in his works “Time’s Arrow,” “Koba the Dread,” “House of Meetings” and “Zone of Interest.” “Ideology brings about a disastrous fusion,” he wrote, “that of violence and righteousness.”

As a reader, the music of Amis’ best sentences stuck with me. As a writer, I took his work off the shelf not just for pleasure but for renewal, recharging the creative adrenal gland when I was blocked and pacing the floors.

The prose from his non-fiction collections “The Moronic Inferno” and “Visiting Mrs. Nabokov” does not feel dated, despite being written decades ago. It is the rare journalism that inspires regular re-reading, unlocking new insights, while waging a war against cliché.

Like earlier eras of literary heroes, Martin Amis traveled in a generational pack. They were a post-punk crew that migrated from the UK to the US, including Hitchens, Tina Brown and Salman Rushdie.

Writers who came up in their shadow and were later lucky enough to work alongside them found their brilliance matched only by their willingness to raise a glass with young people of a similar spirit, if less blessed with raw talent.

I once had the surreal experience of traveling with Amis on a reporting trip to Iowa covering a 2012 GOP debate and having him read my second book “Wingnuts” on the flight as homework. As I sat in the seat next to him, trying to stay cool while listening for any hint of approval, I wondered if he could hear how many sentences were influenced by his work.

In his final book, “Inside Story,” part memoir and part novel, Amis returned to his friendship with Hitchens in the 1970s, prior to their becoming famous. It chronicles a doomed affair, flashing forward at times to the decline of their friend Saul Bellows from dementia, as well as Hitchens’ death. It seemed to hint at a long goodbye of Amis’ own. But the door closed faster than I’d imagined.

Get our free weekly newsletter

Amis received honors and fame, as well as some jealous disdain – but no Pulitzer or Nobel. He got a lot and deserved more.

As I got word of his passing from an alert on my phone, I happened to be watching my children run around at a playground and I recalled one of the many Amis lines that kicks around my cranium – this one from perhaps his most celebrated novel, “London Fields.”

“Watching children in the park…it occurs to me as I try to account for childish gaiety, that they find their own littleness essentially comic. They love to be chased, hilariously aware that the bigger thing cannot but capture them in time.”

In true Amis fashion, those sentences are about death as well as love – with flashes of laughter punctuating the space in between.