Editor’s Note: Khalil Gibran Muhammad is the Ford Foundation professor of history, race and public policy at Harvard Kennedy School and director of the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project, or IARA. Erica Licht is research project director at IARA. The views in this commentary are their own. Read more opinion at CNN.

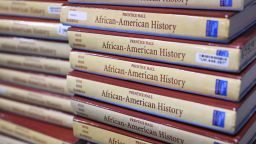

In January, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis announced plans to ban the College Board’s Advanced Placement African American studies pilot course in his state, saying that the curriculum had a political agenda. The College Board has since revised the course amid a storm of controversy — and strong evidence that DeSantis’ administration had a direct influence on the decision to gut it. The outcome, sadly, has meant diminished national education standards for this vitally important coursework.

Now DeSantis is going a step further, announcing plans to end initiatives focused on diversity, equity and inclusion — which frequently are grouped under the acronym DEI — in public colleges and universities across Florida.

The move would effectively dismantle the relatively new efforts to address racial inequality in institutions of higher learning in the state, many of which were put in place following protests over the killing of George Floyd by police.

DeSantis’ anti-DEI proposal would prohibit all public universities in the state from creating and funding DEI programs and would even block the use of private non-taxpayer funding for these purposes. The intention, he freely admits, is to dry up resources for existing diversity programs so that they will “wither on the vine.”

The decision to zero out DEI programs in Florida’s colleges and universities is an attack on data-driven methods that have been shown to result in better performance and retention for students of color and a more racially diverse and effective teaching faculty. But the positive effects of these programs are felt far beyond the classroom.

Universities in Florida and elsewhere are the very laboratories that show us how to achieve fairer and more inclusive classrooms. They are workplaces that model and test these ideas for the benefit of the broader society. DeSantis’ new policy harms students, administrators, educators and parents — particularly people of color, who stand to gain the most when the institutions they find themselves in begin to reflect society’s diversity.

But it also runs counter to a significant body of research that demonstrates that these programs are critical to the inclusive, high-functioning classrooms and workplaces that we should aspire to create in the 21st century. While Florida has become ground zero for attacks on diversity initiatives, DEI efforts are also under assault in other states, including Texas, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Tennessee.

And the onslaught against DEI comes at the very time that business is embracing the benefits of such initiatives. Tech giants Slack and Intel are among numerous companies that have benefited from workplace DEI programs by focusing on building a more racially diverse staff as well as making structural changes that encourage more inclusive decision-making, hiring and contracting.

There is no shortage of studies touting the benefits of more diverse workplaces and diverse institutions of higher learning. A 2015 study by McKinsey found that companies in the top quartile for ethnic and racial diversity in management were 35% more likely to have financial returns above their industry mean. And a 2020 Wall Street Journal report that examined the impact of diversity programs in American business found that diverse and inclusive corporate cultures “are providing companies with a competitive edge over their peers.”

At Harvard’s Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project, we evaluate and disseminate the best evidence for achieving racial equity in organizational structures, policies and practices in the public and private sector through research, convenings and public dialogue.

As part of that work, two years ago we created an open-source database, the Race, Research and Policy Portal, which compiles peer-reviewed research publications on diversity, racial equity and antiracist organizational change. The database affords us a unique opportunity to discern and highlight important academic studies, which are often hidden behind subscription paywalls, and help changemakers find the tools they need.

The move to end DEI in Florida also comes at a time when such initiatives are under duress at institutions of higher learning around the country, with professionals in the field saying they often feel the work that they do is not fully appreciated and supported.

That’s regrettable. Our research tells us that these programs, when structured, funded and resourced effectively, promote civic engagement, reduce bias and prejudice on campus and increase engaged scholarship. In short, embedding DEI efforts within a university strengthens its overall educational mission.

One example of this is at Texas A&M University, where Christine Stanley, professor of higher education and endowed chair in the College of Education and Human Development, and her colleagues have highlighted the success of a long-term university diversity plan. The research-intensive land grant school put its DEI program in place in 2010.

After the DEI efforts were established at Texas A&M, it saw an increase in enrollment of Latinx undergraduate students, an increase in overall job satisfaction for staff, and more focused dialogues around inclusion on campus. The initiative was effective because it embedded its goals, including restructuring hiring and enhancing the overall campus student climate, within the university’s mission of academic success and institutional excellence.

In short, what educators learned at Texas A&M is that breaking a culture of race-blind hiring builds a more effective and robust faculty. Having a more racially diverse faculty results in better faculty retention and performance by students of color.

Here’s another example of DEI success: Román Liera, assistant professor of higher education in the Department of Educational Leadership at Montclair State University, revealed in his study how a DEI initiative at a private university enabled existing faculty to identify problems in hiring processes and make strategic changes.

The religiously affiliated private university he studied, which was given a pseudonym in the published research, redesigned job descriptions and hiring templates, included more staff and administrators in the interview process, required implicit bias training for search committees and ultimately achieved its goal of increasing the pool of talented junior faculty of color.

And in another study, Decoteau J. Irby, an education professor at the University of Illinois Chicago, and Shannon P. Clark, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of African American Studies at Northwestern University, showed how race-specific language can actually improve communication among school leadership teams.

These are just a small selection of hundreds of studies that illustrate how effective DEI programs are in addressing structural and systemic bias in higher education. And they show proven results.

Meanwhile, avoiding the topic of race or using race-evasive language does not reduce racial disparities in student disciplinary action, and it stymies school improvement efforts. Research tells us that when educators are able to speak more explicitly about race and racism, they are more effective at developing school-based procedures, including disciplinary action, resulting in greater racial parity in student outcomes.

Efforts such as those undertaken by DeSantis to undermine DEI programs on campus will undo decades of progress that colleges and universities have made, including urgent efforts in the last two years to address their histories of exclusion among women, people of color, LGBTQ people and other marginalized populations.

It isn’t an accident that the proposed DEI restrictions in Florida come after the ban on AP African American studies. Both are long-standing areas of research committed to equity for all. DeSantis, like Republican leaders in other states, may want to stop progress for political reasons, but social science and data are not on his side.