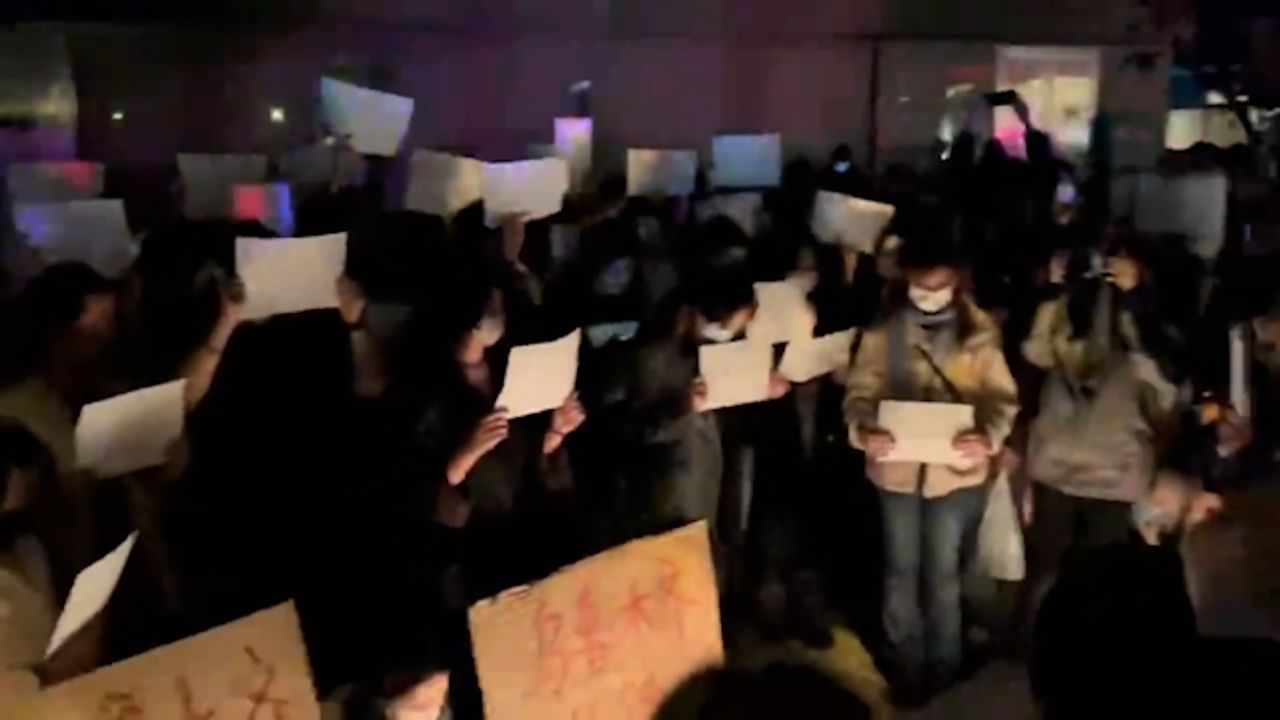

As China attempts to suppress mass protests, the Biden administration is treading carefully in its response – a reflection of the possibility that a full-scale revolt against the Chinese Communist Party could leave the United States in a classic tug of war between its values and strategic interests.

Officials stressed that Washington strongly supports the right of people everywhere to peacefully demonstrate, but have not given any direct indication of support for the protests. Going further could imperil US President Joe Biden’s effort to improve relations between the two countries, after he met Chinese leader Xi Jinping in Bali.

It’s a strategically defensible position, given the need to avoid a clash with China that could spiral into a superpower clash in Asia. But if the protests spread and are brutally put down, Biden will face pressure from both hawks and human rights advocates to take a harder line – and live up to his promise to put promoting democracy at the center of his foreign policy.

He is not the first president to face such a dilemma.

In the run-up to Beijing’s suppression of pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989, then-President George H.W. Bush’s White House was preoccupied with preserving relations with Beijing. In retrospect, though, the administration badly underestimated the ruthlessness of Chinese leaders.

China is unrecognizable since 1989, and recent protests – this time arising out of frustration with Covid-19 lockdowns but expressing some dissent towards Xi – are not fully analogous. But Bush, who was a China expert after serving as top US envoy in Beijing at the dawn of the diplomatic relationship in the mid-1970s, faced the same questions Biden must answer now: How explicitly to speak about the situation in public? What messages – if any – to send in private to Beijing? And ultimately, when does the US instinct to stand up for values of freedom and democratic progress cede to more cynical economic and geopolitical interests?

These conundrums shine through a fascinating set of declassified documents that became public several years ago.

After Chinese soldiers crushed the rebellion in Tiananmen Square, with estimates of the death toll ranging from hundreds to thousands, Bush deplored the use of force and called on Chinese leaders for restraint. But he also stressed that he didn’t want the aftermath of the horror to “break” US-China relations.

However, behind the scenes, there was a real debate about the efficacy of US policy. In a secret cable to Washington, then-US ambassador James Lilley argued that Washington’s overarching goal had blinded it to the real nature of the Chinese regime. “The Chinese declared martial law against their own people in Beijing the day we were cozying up to their military in Shanghai,” Lilley wrote, referring to a US naval visit to the eastern Chinese city. “We were not coping with or anticipating current realities.”

Lilley was not just being wise after the fact. He had warned in a cable in May – the month prior to the Tiananmen Square massacre – that the Chinese military was “ready to strike” against the students and that the US should “distance ourselves from the Chinese authorities who appear to be getting ready to crack down on their own people.”

Global revulsion over the snuffing out of the reform movement left China isolated. But Bush, seeking to avoid an irrevocable fracture with Beijing, sent a private letter “with a heavy heart” to Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping.

He explained that he had forcefully condemned the bloody march into the square because it offended Americans’ reverence for freedom of assembly and democracy. But Bush also wrote that he was resisting clamor at home for tougher action against China and said Deng could ease the situation by ensuring the peaceful treatment of future protests and offering clemency to those arrested.

Several weeks later, he sent his national security advisor Brent Scowcroft on a secret visit to meet Deng. The official and declassified memorandum of their conversation offers an extraordinary glimpse into high-level crisis diplomacy. It reveals that China interpreted even muted US support for the right to protest as evidence of a US effort to seed rebellion against the Chinese Communist Party.

“This was an earthshaking event and it is very unfortunate that the United States is too deeply involved in it,” Deng lectured Scowcroft, adding that Washington had impugned Chinese dignity. The US official explained that Bush was powerless to oppose the House of Representatives, which voted 418-0 to impose stiffer sanctions on China. But Scowcroft also said Bush was “deeply appreciative of your willingness to explain the dilemma in which he finds himself. That’s the message from a true friend of the Chinese government and the people of China.”

It’s impossible to imagine a similar conversation unfolding today between a US delegation and Xi, partly because China is far more powerful and Washington is far more openly hostile to Beijing’s domestic repression and global ambitions.

Bush has been accused of appeasement. Some historians have argued that his obsequiousness to Deng encouraged China’s decision to develop as a hostile, nationalist power that in many ways defines itself through its defiance of the United States. But others suggest that Bush was correct to try to avoid the kind of superpower standoff that has since developed and that makes Biden’s decisions today considerably more fraught.

In the end, Bush came down in favor of a hard-nosed judgment of US national interests over ideals. Biden would be likely to show far less deference to Beijing given today’s broad, bipartisan anti-China feeling in Washington. But with China now a strong military power threatening Taiwan and increasingly keen to confront Washington, it’s hard to imagine he would ultimately take a different course of action.