Editor’s Note: Thomas Balcerski is the Ray Allen Billington Visiting Professor of U.S. History at Occidental College and a Long-term Fellow at the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens. He is the author of “Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King” (Oxford University Press). He tweets about presidential history @tbalcerski. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

In an interview with “60 Minutes” on Sunday, President Joe Biden said it was “much too early” to decide whether he will run again in 2024 – adding uncertainty to an already unsettled political landscape.

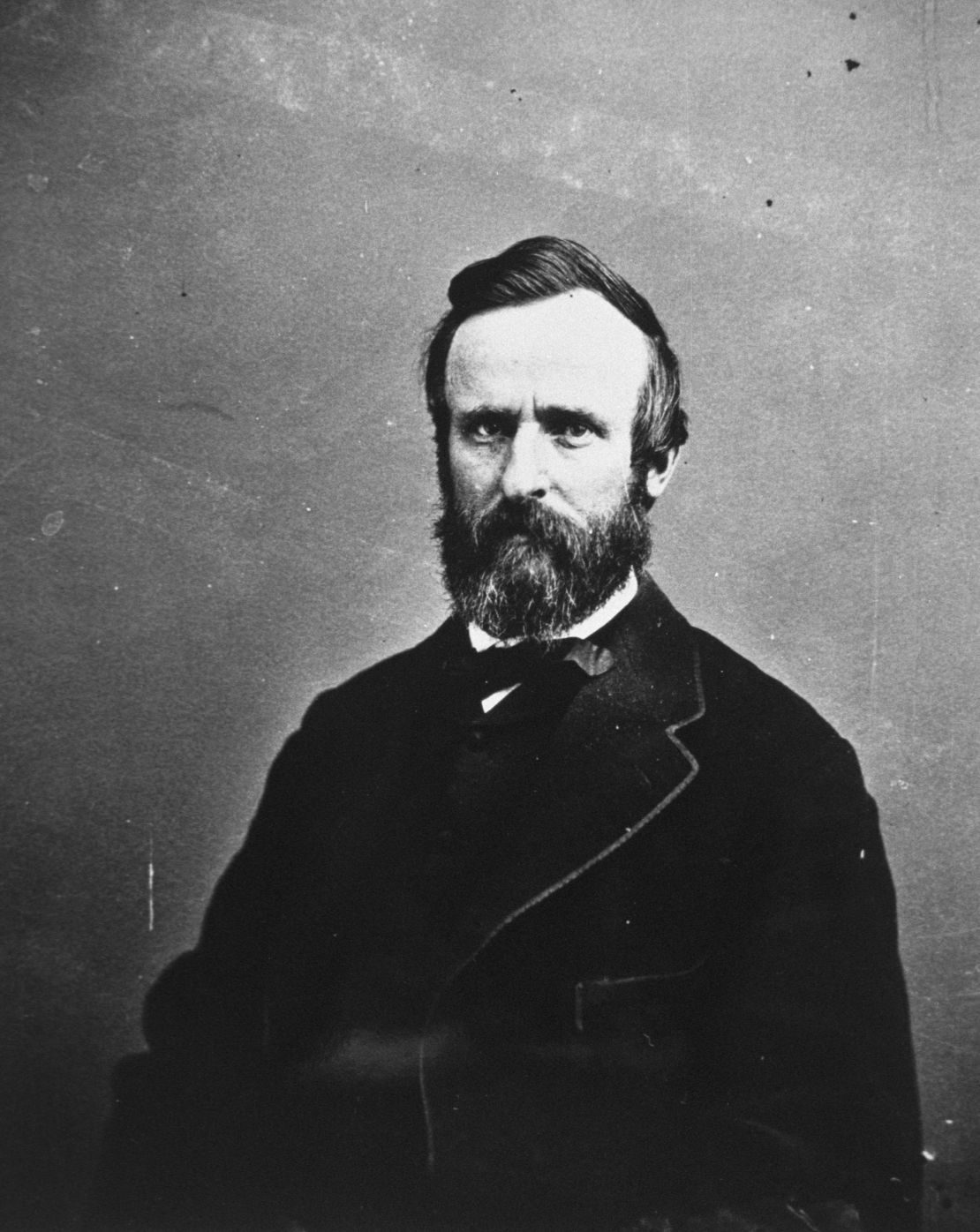

Though Biden still has time to make his decision, he should consider another factor: the weight of history. Should Biden choose not to run again, he would be the first first-term incumbent president not to do so since Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876.

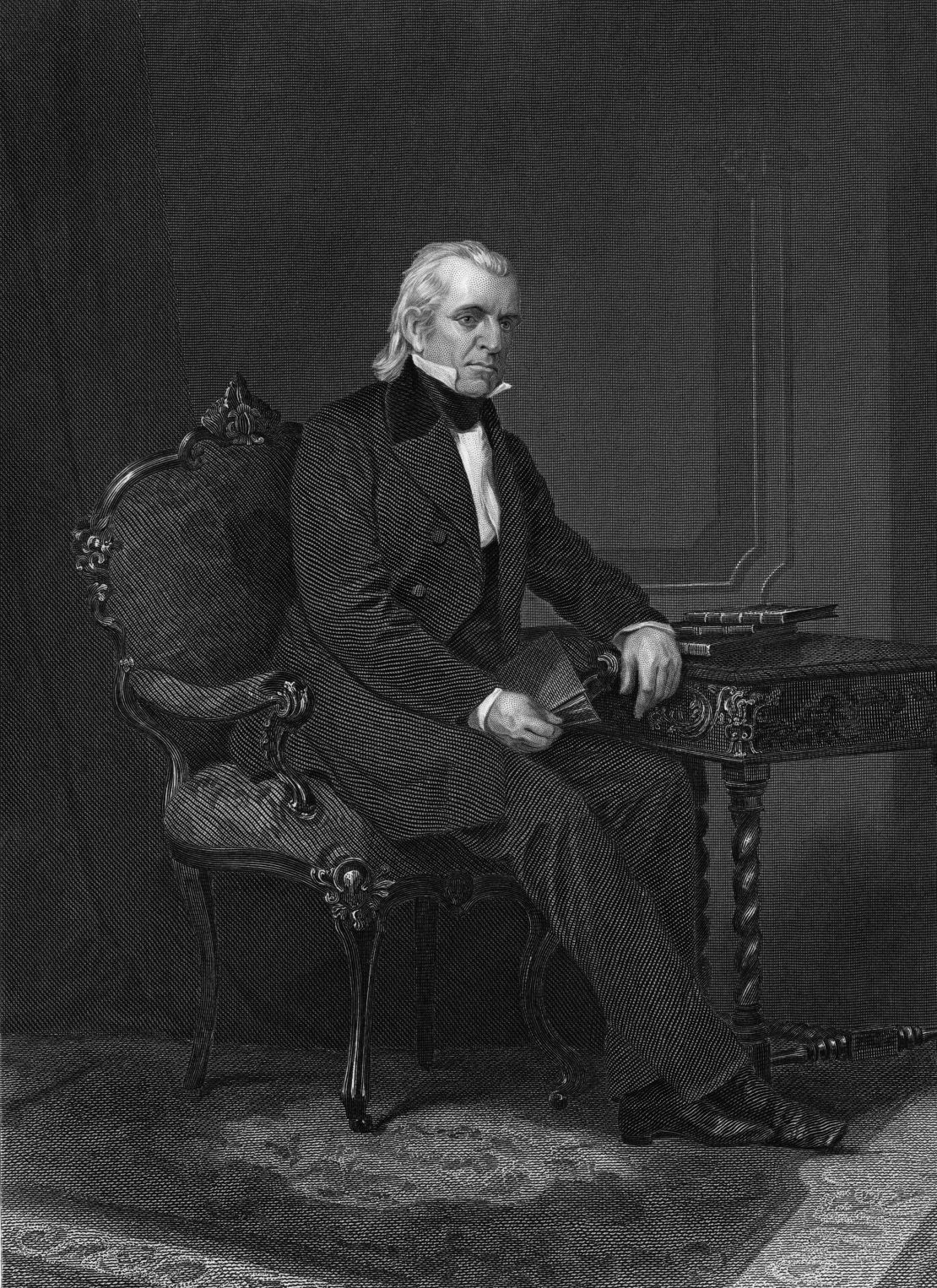

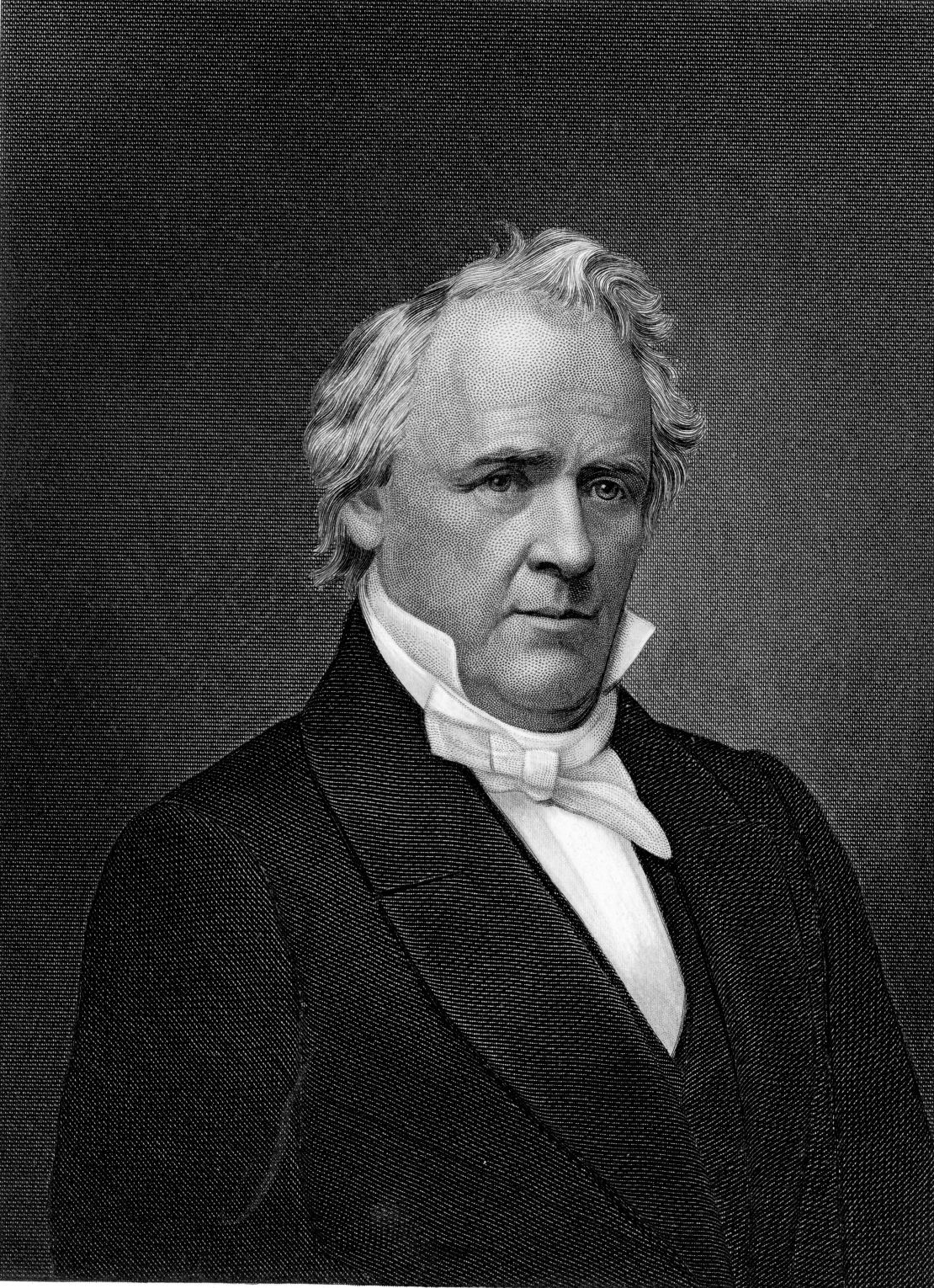

Indeed, only three incumbent first-termers – James K. Polk, James Buchanan and Hayes – announced that they would not seek a second term. More often than not, the decision led to electoral uncertainty and defeat for the party in power.

At issue is how the power of incumbency acts as a stabilizing force for the party in power. When a sitting president decides not to seek another term, it can create a political vacuum that the opposition party can take advantage of.

This dynamic first developed in 1844, when the “dark horse” candidate, James K. Polk, emerged out of the 1844 Democratic National Convention as a relative unknown. In a letter accepting the nomination, Polk pledged to serve one term as “the most effective means…to make a free selection of a successor who may be best calculated to give effect to their will, and guard all the interests of our beloved country.”

As President, Polk proved that a one-term president could still be effective. He used his time in office to pursue several objectives, among them what became known as “Manifest Destiny,” an ideology that the United States was destined to expand across the continent, and which became a precursor to war with Mexico and thousands of miles of territorial gain. That he also had predicted that he would accomplish all of his stated goals coming into office has marked him as one of the most impactful one-term presidents in American history.

But if Polk’s pledge to serve a single term was meant to leave the door open for other Democratic leaders to succeed him, it also weakened the party’s future prospects. As a pre-condition for serving in his cabinet, Polk required that every member of the cabinet promise not to run for president.

With the field narrowed, the Democrats settled on the aging politician Lewis Cass of Michigan, whose support of popular sovereignty alienated the anti-slavery wing of the party and caused many to defect to the third-party Free Soil Party. In response, the opposition Whig Party seized the moment by running the popular war hero General Zachary Taylor. In the end, Taylor and the Whigs captured the presidency by a narrow majority.

In 1857, Buchanan, also a Democrat, followed Polk’s precedent, pledging in his inaugural address “not to become a candidate for reelection.” Age may have played a part in his decision – at 69, he would have been the oldest man ever to serve by the end of his term.

But Buchanan’s single-term pledge, rather than unifying the party for the four year term, led to a rivalry with Stephen Douglas, who hoped to secure the nomination in 1860. The feud eventually split the Democratic Party in half between the Douglas faction and the administration’s preferred candidate, John C. Breckinridge, and paved the way for the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln.

After Buchanan, the next president to pledge to serve one term was Hayes. He declared his attention to retire after four years while accepting the Republican nomination in 1876. A man of principles, Hayes did so primarily to prevent the corrupt system of political patronage from being used as a pre-condition to him being nominated for a second term.

But if Hayes hoped to fix the broken system of appointment through this pledge, the problem only grew worse. His successor, James Garfield, was assassinated by a disgruntled office-seeker emboldened by rumors of a patronage deal.

Since Hayes, no first-term president has decided to not try for reelection, though some second-term presidents have chosen not to seek their party’s nomination – Calvin Coolidge in 1928 and Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968. Both men were vice presidents who had filled out significant periods of their respective president’s first terms (thus allowing them to consider running for another term).

Nevertheless, Johnson’s surprise announcement that he would not seek a second full term resulted in political chaos. When Johnson announced a partial pause in bombing and desire to seek a settled peace in Vietnam, he inadvertently undercut the party’s candidate, Hubert Humphrey, and handed Republican candidate Richard Nixon a free pass on explaining how he would achieve an “honorable peace.”

A notable exception, Theodore Roosevelt vowed that he would not seek a second full term in 1908 – a decision he immediately regretted. Roosevelt went on to challenge William Howard Taft for the Republican nomination in 1912, only to run as a third-party Progressive candidate and lose to Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

What does this history of determined one-termers tell us about Biden’s decision to run – or possibly not run – again? First, it’s a rather uncommon feature of the American presidency for an incumbent not to seek a second term. In each of the three instances, the president had made the decision not to run either before the actual election or early on in his term. By contrast, Biden has previously stated that he would run again if “fate” allowed.

Second, Biden’s latest commentary seems to underestimate the real risks of becoming a lame duck president years before his four-year term comes to an end. By announcing too soon that he will not run again, he could weaken his party’s position in future elections. Less a well-intentioned pledge to unify the party ala Polk, such a move would instead appear to be capitulating to political pressures along the lines of Johnson.

Finally, in determining whether to step aside, Biden should consider whether, like his predecessor Polk, he has accomplished all that he set out to do at the outset of his four-year term. Otherwise, he risks going down in history as a one-term president who fell short, joining the ranks of Hayes and Buchanan.

In the end, the choice of whether to run or not rests solely with Biden. But if Biden chooses to run for another term, he will be following the majority of first-term presidents who came before him. It remains to be seen whether such a decision will ultimately lead to electoral victory or defeat for his party in 2024.