Editor’s Note: Alice Driver is a freelance journalist whose work focuses on migration, human rights and gender equality. She is based in Mexico City. Driver is the author of “More or Less Dead: Feminicide, Haunting, and the Ethics of Representation in Mexico.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author. View more opinion on CNN.

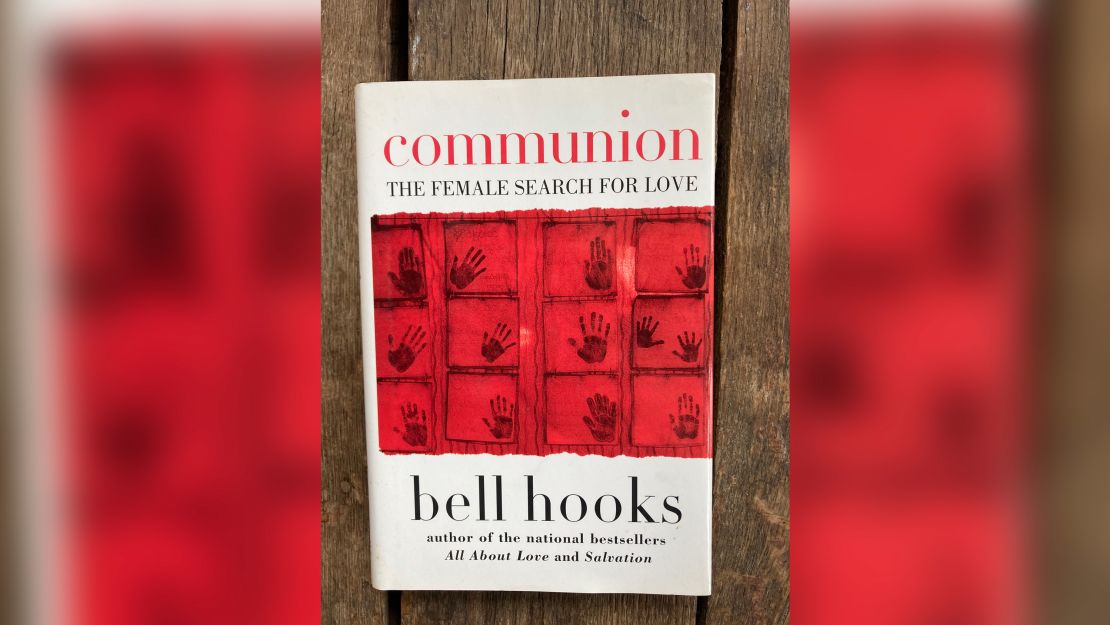

In 2004, while waiting for customers at the local coffee shop where I worked in Berea, Kentucky, I wrote in my notebook, “The one person who will never leave us, whom we will never lose, is ourself. Learning to love our female selves is where our search for love must begin.” I read bell hooks’s “Communion: The Search for Female Love” – the book from which this line is taken and whose words have stayed with me ever since – during my free time at work, storing it under the cash register when I had customers. I had discovered “Ain’t I a Woman” – hooks’s most famous book – in a women’s studies course at Berea College. It was my first encounter with a more inclusive idea of feminism, one that centered the experience, history and labor of Black women.

I remember waiting for hooks to enter the coffee shop so I could meet her in person and ask her to sign her book. Growing up in Arkansas, I struggled to find writers whose stories reflected the challenges of being a woman in rural America. I found hooks – as a woman from rural Kentucky – relatable, her essays and criticism as inviting as they were incisive.

I had graduated from Berea College with an English major in 2003. Berea hired hooks after I graduated, so I did not get to take a class with her, but I did see her radiant self regularly at the coffee shop. I wanted to ask hooks for writing advice and have her sign a book for me, but I had to build up my courage to approach her. I was afraid to admit how badly I wanted to be a writer. At that time, I had only sold one article for $20, and I did not feel like one yet.

When I think of hooks, who died Wednesday at age 69, I am reminded of the way she made Black feminist theory accessible to the different communities she inhabited, changing lives with her inclusive and radiant energy and words.

She was born in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, in 1952, when the town was still segregated. In 2016, hooks wrote that when her dear friend Gloria Steinem had asked her why she was returning to Kentucky, she realized: “Although it was not her intent, these words conjured stereotypical images of Kentucky – tin can trailer parks, poor White trash rednecks, broken-down pickup trucks, dirty, uneducated folks – Black and White – and even more profoundly the absence of any progressive face. It is just these negative images of Kentucky that I had left behind.”

I deeply respected her decision to return to Kentucky as I had similarly complicated feelings about Arkansas, where I grew up. I read the biographies of authors I respected obsessively, and many of them reflected the idea that New York and San Francisco – cities that I had never visited – were the epicenter of the writing world, of intellect and ideas. Like hooks, I felt like I had to leave behind certain negative images of Arkansas, the stereotypes that others recounted to me about impoverished, uneducated mountain folk.

I desperately wanted to be a writer, but I didn’t know how to make money writing. Instead, I was making lattes while living in a cabin with an outhouse in the woods. I had grown up in the rural Ozark Mountains with an outhouse, and I thought that living in such conditions would allow me to save money. And I hoped that by saving money I would be able to make space to write. I believed, as hooks wrote in “Communion”: “… the truth is that finding ourselves brings more excitement and well-being than anything romance has to offer, and somewhere we know that.”

I knew since my first memories that I wanted to be a writer, and my love of writing held more interest for me than any romantic relationship. In hooks, with her focus on making feminist intellectual and theoretical work accessible, I found a companion. Hooks made me feel less alone and strange in a world that generally celebrated women for milestones related to traditional romance such as marriage and children. In “Bone Black: Memories of Girlhood,” she wrote, “This is my home. This dark, bone black inner cave where I am making a world for myself.” As she did for me, she showed so many how to make a feminist life, a writing life, outside of the stereotypical narratives offered up to women.

Berea College is one of the eight federally recognized work colleges in the US, meaning that the college accepts low-income students and students work on campus in exchange for tuition. I was thankful to have graduated from Berea College with no debt, a rarity among my friends, many of whom accumulated tens of thousands of dollars in debt. While at Berea, hooks – the Distinguished Professor in Residence of Appalachian Studies – opened the bell hooks center, an inclusive space for historically underrepresented students. In 2017, she dedicated her papers to the college, ensuring that future students would have access to her work.

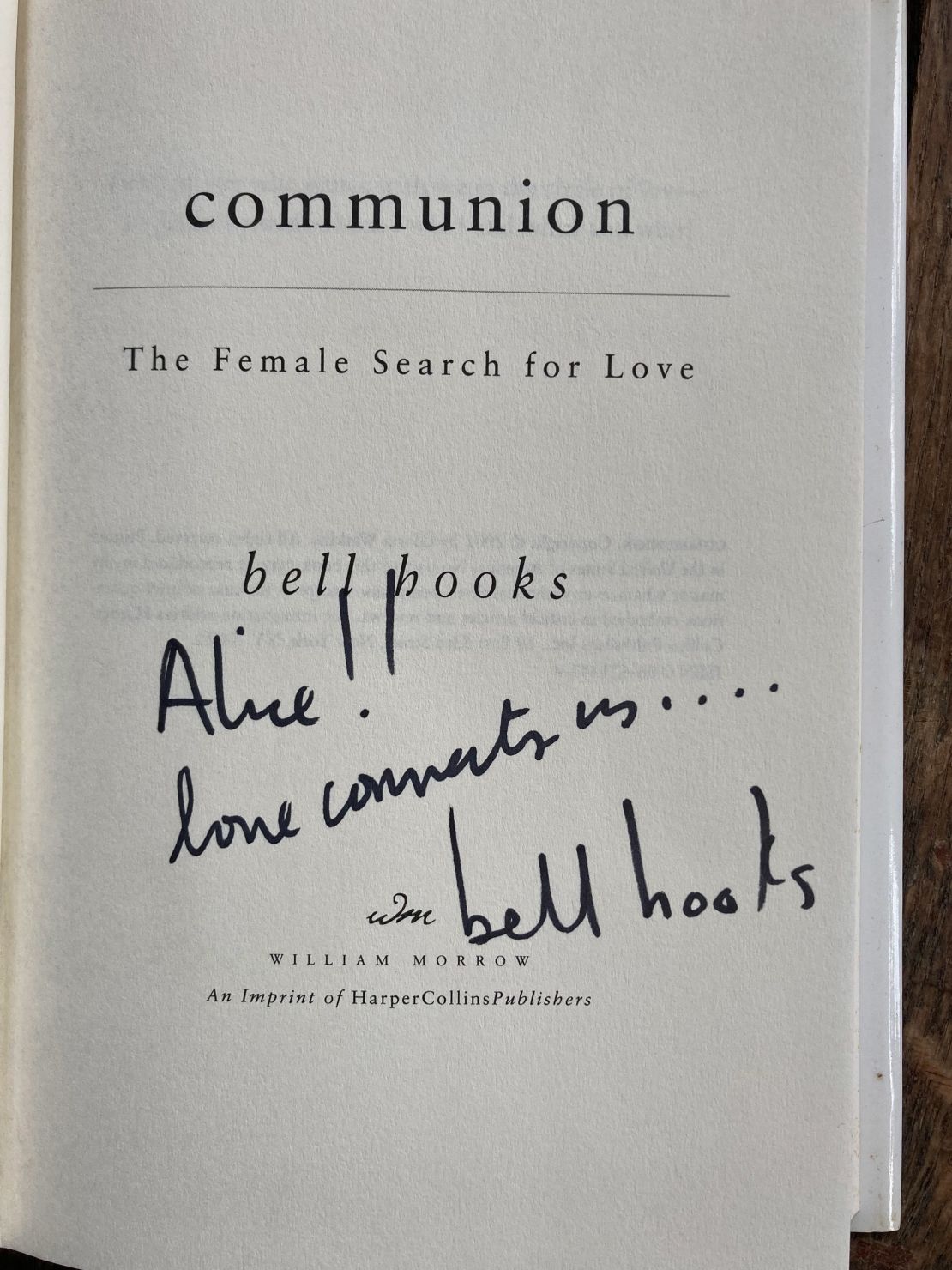

When I first met bell hooks at the coffee shop, I was surprised by how tiny she was and her joyous energy, which made people turn toward her as if she were the sun and they sunflowers. It took me a few weeks to build up the confidence to approach her. One morning when she ordered coffee, I pulled “Communion: The Search for Female Love” from underneath the register. She wrote, “Love connects us …” in her dedication, and she told me to keep writing. Her words buoyed me through that tumultuous year, and I did keep writing. I haven’t stopped.

I returned to Berea College in 2015, the year I published my first book, to see bell hooks in conversation with Gloria Steinem. I carried hooks, her words and her life, with me then, as I do now – and will always.