Editor’s Note: Gene Seymour is a critic who has written about music, movies and culture for The New York Times, Newsday, Entertainment Weekly and The Washington Post. Follow him on Twitter @GeneSeymour. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author. View more opinion on CNN.

How do you embrace a mountain?

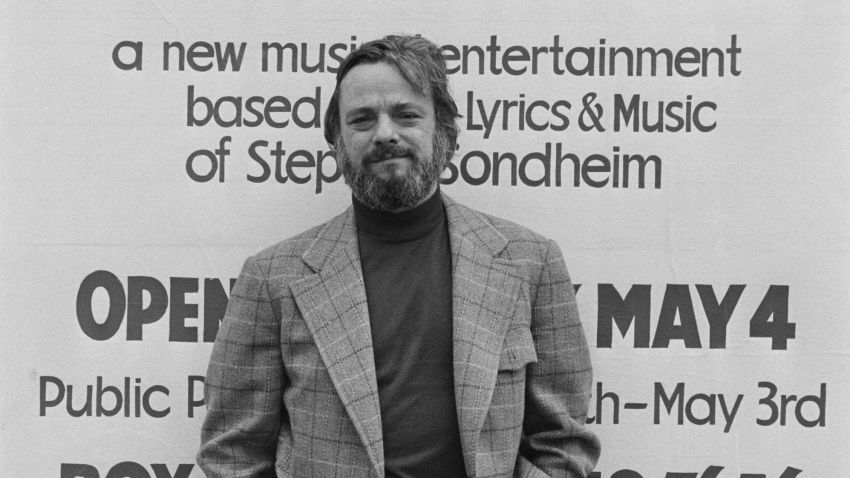

In so many words, that’s what the world-at-large has been asking itself since Friday morning when Stephen Sondheim, the greatest Broadway songwriter of the 20th century’s latter half and beyond, died at 91. He leaves behind a formidable and imposing body of work that remains visible, relevant, intellectually stimulating and emotionally enrapturing.

Sondheim, lived, worked, and flourished long enough for people to compare his body of work to William Shakespeare’s. Once you’ve reached that level of acknowledgment, one presumes – at the very least – that you can take a knee, stretch out, chillax, maybe spend more time doing crosswords or working out all the other word games the master lyricist liked to play.

But if the wave of media tributes, career overviews, front-page obituaries and their dozens of sidebars are indicative, Sondheim wasn’t much into resting – most especially upon his many laurels. Though he had recently been afflicted with health issues (that as of Sunday remain unspecified), Sondheim was still conducting interviews about his staggeringly broad and enduring oeuvre, from the recently opened off-Broadway revival of “Assassins” to the forthcoming reimagined version of “Company,” in which the protagonist, played by male actors since its original premiere in 1970, would be portrayed by a woman.

There was even the prospect of yet another original musical, “Square One,” an adaptation of two movies by the Spanish surrealist Luis Buñuel that Sondheim had been working on for years with playwright David Ives.

And next month, after delays related to the coronavirus pandemic, Steven Spielberg’s long-awaited movie revival of “West Side Story” will finally open in theaters, reminding the known world (as if it needed such reminders) of Sondheim’s spectacular Broadway breakthrough in 1957 as lyricist to Leonard Bernstein’s music and Arthur Laurents’ libretto updating “Romeo and Juliet” from Italy at the hinge of the 13th and 14th centuries to the meaner streets of upper Manhattan in the middle of the 20th.

He started out reworking with Shakespeare, and ended up as his only peer: Is this an exaggeration? If so, this column is hardly the first to make it. As recently as 2009, when Sondheim was a mere 79 years old, British director Trevor Nunn, whose credits include “Cats,” “Starlight Express” and the epochal dramatization of Charles Dickens’s “The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby,” told Time magazine he believed Sondheim’s preoccupations and gifts were in almost eerie alignment with the Bard of Avon’s.

They both, Nunn said, “are fascinated with the contradictions of human beings, with their complexities and ambiguities. As with Shakespeare, there’s heightened poetic expression in Sondheim, but when you dig into it, you find it’s in touch with something real.”

Indeed, any musical soliloquy – and there are dozens of them – from Sondheim’s collected works are such compendiums of emotional range and complexity that they can be viewed as mini-dramas of their own. Since I now have the floor, I am willing to declare, “Being Alive” from the aforementioned “Company” to be the closest thing in Sondheim’s vast and diverse output to Hamlet’s “To Be or Not To Be” monologue.

In counting down in his head all the reasons for making a romantic commitment he fears, the musical’s main character Robert rummages through all manner of contradictory evidence (“Someone to need you too much/Someone to know you too well/Someone to pull you up short/To put you through hell…”) But towards the end, he realizes he’s not looking for justifications for loving, but for living because “…alone is alone/not alive…”

While “Being Alive,” on its surface, may not seem as virtuosic in verbal ingenuity as some other Sondheim works, it’s the deceptive simplicity of witnessing a mind in conflict with itself that ends up overwhelming your expectations.

And there are many such examples of such individual testimony, whether it’s “I’m Still Here” or “Losing My Mind” (or indeed any number) from “Follies” or “Finishing the Hat” from “Sunday in the Park with George” or the poignant title song from “Anyone Can Whistle” and on and on.

To get back to the question we started with, it may not be necessary to “embrace” the totality of Sondheim’s legacy, one which transformed the landscape of musical theater and raised the genre’s artistic ante. All you need do is wander back and forth and back again through the repertoire.

Even if you think you know most – or all – the songs and stories, the countless revivals, restorations and even reinventions of Sondheim’s musicals have already suggested there are still many more discoveries to be made.

And even if Sondheim’s time on earth is up, the rest of us have plenty of his output to make our way through – it could last as many centuries as Shakespeare’s work has persisted and come to as many different conclusions about what those kerjillions of words mean.

So, wander. Don’t try so hard to embrace the work. Let it embrace you.