Against the backdrop of unprecedented heat waves and deadly wildfires, the West’s historic drought has ranchers fighting another problem besides water shortages: a prolific hoard of grasshoppers is competing with cattle for food.

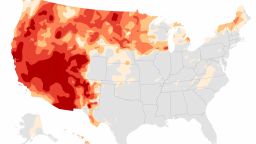

Around 93% of the West is in some level of drought this week, and a bizarre impact of this pernicious dry condition is the explosion of the grasshopper population. Grasshoppers have devoured so much vegetation that many ranchers fear rangelands could be stripped bare.

A 2021 grasshopper hazard map from the US Department of Agriculture shows each square yard of land contains at least 15 grasshoppers in parts of Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Arizona, Colorado, and Nebraska.

“Climate change is a concern to all of us, and when we see extreme events such as a very bad drought, we see natural phenomenon increase such as grasshopper outbreaks,” Sharon Selvaggio, a former US Fish and Wildlife Service biologist, told CNN. “It’s very concerning.”

Grasshoppers, which thrive in hot, dry weather, have been defoliating trees and competing with cattle for food — and the bugs are winning. Ranchers are selling cattle “due to poor forage conditions and a lack of feed,” according to the latest US drought monitor.

Federal agriculture officials say they saw the outbreak coming after a 2020 survey that found a heavy concentration of adult grasshoppers in the West.

“Uncontrolled infestations could cause significant economic losses for US livestock producers by reducing forage available on rangeland and therefore forcing producers to buy supplemental feed or sell their livestock at reduced prices,” the USDA said in a statement last year, announcing a grasshopper suppression program.

To mitigate further drought-fueled economic impacts, the agency has launched a grasshopper-killing campaign — the largest since the last outbreak in Montana in the 1980’s.

Agriculture officials plan to aerially spray more than 2.6 million acres of Montana grasslands with insecticides in an attempt to kill grasshopper populations. That’s an area larger than both the state of Delaware and Rhode Island combined.

It’s not the right approach said Selvaggio, now a pesticide program specialist for the Xerces Society, a nonprofit conservation group that protects insect habitats, adding that it will be ineffective in the long-term.

“The problem with insecticide treatments is that it could actually worsen grasshopper outbreaks in the future by harming the natural enemies or grasshopper competitors which, under natural conditions, serve to limit pest grasshoppers,” Selvaggio said.

A 2021 environmental assessment on spraying insecticides in Montana reported no significant impacts of widespread insecticide treatment. Xerces Society and other environmental groups pushed back on the assessment pointing to a “lack of specificity and clarity” in the report.

The USDA says it will only spray in low concentrations to kill grasshopper nymphs, since adult grasshoppers require larger amounts of insecticides.

And while grasshoppers do tend to emerge during particularly hot and dry years, environmentalists say their mass appearance depends on many compounding factors, including a changing climate.

Birds, for instance, prey on grasshoppers. But the population of grassland bird species are declining, disrupting the natural cycle of grassland ecosystem. Vegetation cover, Selvaggio adds, has also been decreasing, in part due to how grazing is conducted, which in turn speeds up grasshopper development.

“We need to think about it as a system, not just the symptom of the problem,” she said. “Grasshoppers are the symptom of an ecosystem that’s out of balance. We need to examine the role of vegetation cover and diversity.”

Selvaggio likens grasshopper disturbance to fire, emphasizing that aggressive fire suppression practices in the West never worked to eliminate the long-term risk. Spraying insecticides to rid rangelands of grasshoppers, she says, will have the same result.

“We need to embrace a management approach that emulates the natural disturbance regime that’s considered a better way to make forest and fire resilient,” Selvaggio said. “We need a similar approach for grasshopper management on rangelands.”

A recent climate assessment of the greater Yellowstone area, which is part of the region with dense grasshopper populations, has warned of significant changes such as invasive species outbreaks in the region as the planet warms.

This year’s drought and heat waves have been record-breaking — a clear signal that climate change is already impacting all aspects of life. And because of these extreme weather changes, Selvaggio says the way land and ecosystems are managed matters.

“Climate change may bring us more grasshoppers in the future in increased frequency, duration or severity,” she said. “We need those long-term solutions to address grasshopper for the long-term because we do know that we may be facing more of this in the future if we don’t really take this seriously.