Editor’s Note: Clay Cane is a Sirius XM radio host and the author of “Live Through This: Surviving the Intersections of Sexuality, God, and Race.” Follow him on Twitter @claycane. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his. View more opinion articles on CNN.

There’s a quote I live by from the late, great writer Zora Neale Hurston: “I am not tragically colored.”

Her words, from her 1942 autobiography, “Dust Tracks on a Road,” encapsulate how I, and many others, navigate our identities.

I am not “tragically” Black or gay – meaning, who I am is no great trial to overcome or eternal punishment to exorcise. Which isn’t to say that navigating racism, homophobia and religious bigotry hasn’t been treacherous for me at times. But something in my soul always knew I was more than an inhumane statistic and not subject to anyone’s damnation.

This confidence and demand to be heard is where many of us are today, especially Black queer folks in media and beyond. As we come upon LGBTQ Pride Month in June, our representation is unstoppable.

FX’s series “Pose” is one of those vehicles for storytelling. The Ryan Murphy series, in its third and final season, follows Black and Latinx youth in New York’s underground ballroom scene during the 1980s and 1990s. The ballroom scene encompasses fashion, dance, creativity and, most important, family and community. During the era “Pose” depicts, ballroom was often a refuge from violent homophobia and racism.

As “Pose” comes to a close, its legacy is a rarity in mainstream media: Black and brown queer folks at the center of telling their own stories. There is no going back now to the days of being reality show sidekicks or the tragic closet case. “Pose” has helped to give agency to the previously silenced and to forge a road ahead for a wave of Black queer storytelling to continue, capturing key moments in our history that only we can tell.

The tragic figures here are those who hate, not the survivors

The ballroom scene first received mainstream attention with the 1991 documentary “Paris Is Burning,” which, to some, was entertaining and illuminating but to many others was also deeply exploitative, since Livingston – who launched her career with the documentary – was a White filmmaker from New York University (NYU) with no discernible connection to the ballroom community.

“Pose” is different. Unlike “Paris Is Burning,” it’s written and directed by Black and brown queer people with members from the ballroom scene as consultants.

The May 16 episode, “Take Me To Church,” was powerful and a beautiful snapshot of what many queer folks, especially Black and brown, have endured.

The character Pray Tell, brilliantly played by Emmy winner Billy Porter, goes home to his religious family after 20 years of estrangement. He reveals he has AIDS with only months to live. Immediately, he is met with hateful religious dogma; his mother leaves the room and his aunt says, “love the sinner, hate the sin.” In one emotional scene, he calls them out for shaming him: “Sometimes I think I wouldn’t have this disease if it wasn’t for the church and how y’all treated me.”

This powerful moment echoes a familiar message that was seen in the recent British miniseries “It’s a Sin,” also set during the AIDS crisis, when one character tells a homophobic mother that boys everywhere are dying of shame – a shame that comes from dangerous doctrines and delusional parents.

When Pray Tell’s mother insists that he stepped away from the church, he corrects her: “The church stepped away from me.”

This isn’t the story of a downtrodden, dying Black gay man begging for love. Pray Tell is undefeated. The tragic figures are those who ostracize him, intentionally or unintentionally.

That is the brilliant and ongoing theme of “Pose.” The tragedies are the people who hate and cannot change, not the beautiful survivors who evolve.

A character refusing to be victimized and the mainstreaming of this liberating narrative, can impact the lives of many LGBTQ+ people. The commentary from “Pose” on how past and present homophobia manifests, specifically for Black queer people, shifts our understanding of queer life, history and, quite possibly, frees others.

‘Hollywood cannot say it’s not bankable’

Steven Canals, co-creator and executive producer, has said his adolescence would have been much different if “Pose” existed when he was a child struggling with identity.

Canals told me it was crucial for the show to present the lives of queer folks, specifically trans individuals, as more than horror stories.

“The trans characters are not figuring out their identities. All the trans characters in our show are self-actualized women who are just living their lives. They are trying to occupy space, capture their dreams and live fully, just like everyone else. For a lot of people – that seems like such a radical act.”

Dyllón Burnside, who plays the character Ricky Evangelista on the show, said to me, “‘Pose’” – which consistently trends on social media and whose second season was ratings gold – “proves that you can have stories that exist in a mainstream space about marginalized people or people of all walks of life and Hollywood cannot say it’s not bankable.”

The show’s success likely helped opened the door for HBO Max’s “Legendary,” which orchestrates a real ball with contestants competing for a $100,000 cash prize. (HBO Max, which also aired “It’s a Sin,” shares a parent company with CNN.) Season one premiered in 2020 and season two is currently streaming.

For some, Black queer storytelling can - perhaps should - be more radical

Alyssa Katiar Lavoux Ebony, a transgender woman who started participating in the ballroom scene in 1983, is proud of both shows. She told me, “They adapted very well to our community and the ballroom aspect of it. I really loved what they depicted within the storylines. I’m proud of their work.”

She said she adores the pageantry, but when it comes to the experience of Black and Latinx trans women in ballroom, Ebony emphasized, with a laugh, “It’s not as easy as it looks.”

The show is aspirational but, for some, Black queer storytelling can be – and perhaps should be – even more radical.

Ebony points out that like any fictionalized account, “Pose” did some “clean up” in its depiction of what many trans women of color faced in the 1980s and 1990s, but she was pleased with how her community was represented: “The community or anyone watching ‘Pose’ did not need to see the disgust of what we went through. They needed to clean it up and it was tastefully clean. It was enough information to get what we went through at that time.”

Ceasar Williams, the CEO of Ballroom Throwbacks/BrtbTV and a known figure in the ballroom scene, agreed but noted that just because someone is Black and LGBTQ+ doesn’t guarantee an ability to relate to the ballroom community. In 2014, years before “Pose,” he created the popular YouTube series “Triangle,” now in its sixth season, which presents the stories of Black queer people in a raw, unvarnished context.

Despite his own embrace of grittier themes, Williams insisted the FX show and “Triangle” should both be able to exist.

What the overlap - and distance - between fiction and history reveals

As creators in the community continue to think beyond representation, FX’s separate documentary series “Pride” is airing as “Pose” is concluding. Its take on history showcases the evolution of the LGBTQ community from the 1950s to today.

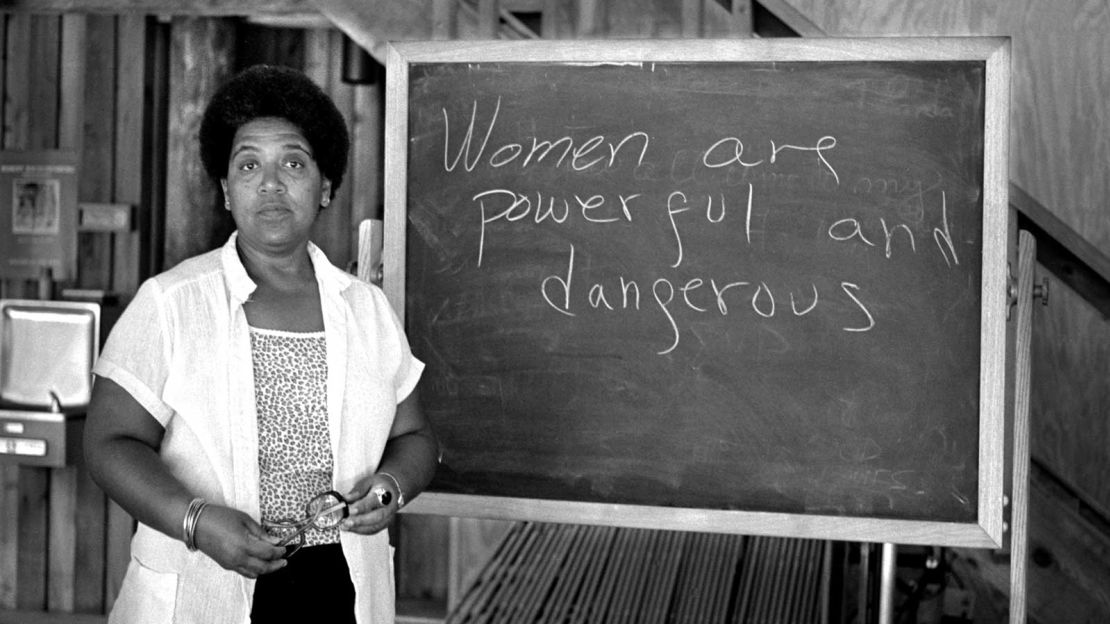

The iconic poet Audre Lorde is featured, and while she died in 1992, she is the perfect blueprint for Black queer storytelling in 2021 – someone who insisted on including same-sex themes in her work, regardless of the backlash. She is a reminder of the resiliency of marginalized groups and an example of how to fight back while refusing shame.

Billy Porter, who recently revealed he has been HIV-positive for 14 years, is also fighting back against shame.

“The shame of that time compounded with the shame that had already [accumulated] in my life silenced me, and I have lived with that shame in silence for 14 years. HIV-positive, where I come from, growing up in the Pentecostal churchwith a very religious family, is God’s punishment,” he told The Hollywood Reporter.

The actor, done with the shame, boldly added, “This is what HIV-positive looks like now.”

Porter is the real-life embodiment of his character Pray Tell’s 1994 dreams for the future – a Black gay man from the church who became a star and still carries the legacy of those who came before him. That seemed nearly impossible in the mid-1990s.

The overlap – and the distance – between Porter the man and Pray Tell the icon he portrays mirrors the moment we’re now in, when shows like “Pose” can influence audiences’ understanding of history rendered in documentaries like “Pride.” Porter – and Pray Tell – are simultaneously stewarding the legacy of many thousands of queer people who have lost their lives to HIV/AIDS – and to manifestations of others’ hate, like murder, poverty and suicide.

Times are changing but our right to exist is still fragile, as recent legislation targeting the LGBTQ community at the state level makes all too clear. Dangerous conservatism is always looming. Our recent visibility on screen is a crucial dimension of a broader social refusal to cower – or limit our existence to corporatized Pride parades.

Back to Zora Neal Hurston. In 1928 she wrote, “Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company?”

Well said Miss Zora, well said.