Editor’s Note: Tess Taylor is the author of the poetry collections “Work & Days,” “The Forage House” and most recently, “Rift Zone” and “Last West: Roadsongs for Dorothea Lange.” Views expressed in this commentary are solely hers. Read more opinion articles on CNN.

Often, these days, I find myself thinking about what Americans struggling to emerge from the coronavirus pandemic might learn from Dorothea Lange

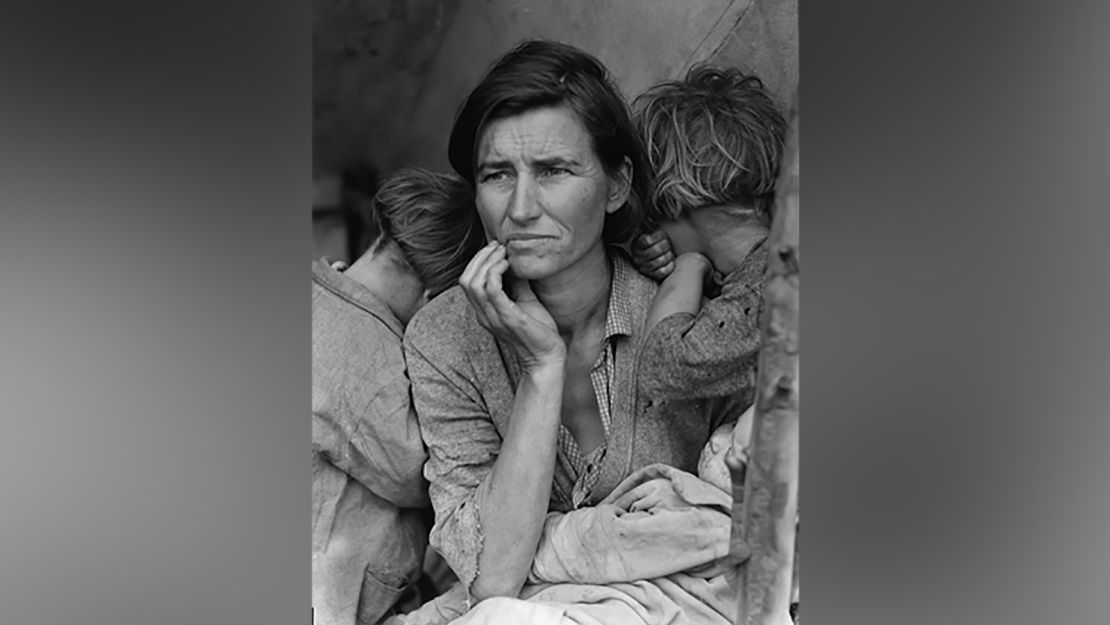

Many people remember Lange as the Bay Area photographer who worked with the Farm Security Administration during the New Deal, photographing the living conditions of migrant laborers amid the Great Depression. Even now, her shots are iconic: White Angel Breadline, a relief and food line photographed outside her San Francisco studio in 1932; a careworn woman with three kids, taken in Nipomo, California, 1936, which came to be known as Migrant Mother.

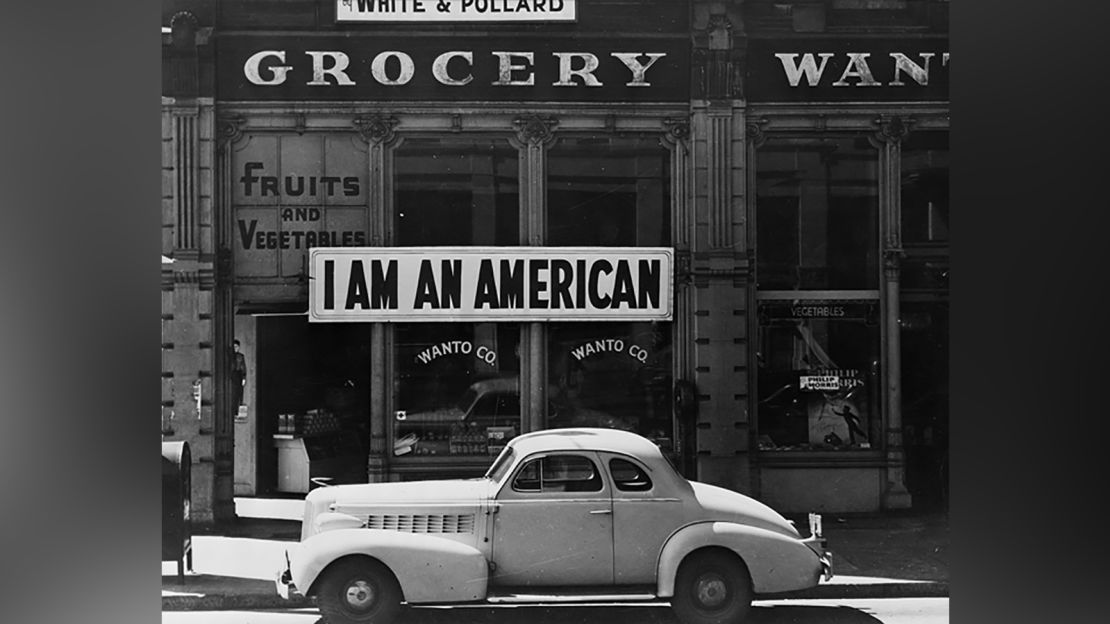

Other Lange shots frame uneasy juxtapositions: “On the road to Los Angeles,” shows itinerant men carrying their bundles up a long road under a billboard that reads: “Next time try the train.” Lange also made poignant records of the tragic and shameful moment when Japanese Americans, a huge number of whom were minors, were forcibly removed from their homes and transported to internment camps. In fact, the subjects Lange photographed – migrancy in the face of climate change, American internment, the fragility and beauty of the land that feeds us – were eerily prescient.

There well may be a Dorothea Lange alive today. In fact, in another moment of deep American stress – as we crawl out of this crippling pandemic and try to heal some of our festering divisions – America has a whole trove of makers, documenters and humanists at our disposal, eager to bear witness and work toward repair. Lange’s efforts remind me there is a lot American artists could do right now for the common and public good.

As we think about the upcoming infrastructure bills and the restorative efforts beyond them, it’s worth considering how the cultural components of a new deal – including ones like the widespread integrated arts programs that funded Lange’s work – could spur the economies of today, rebuild and stabilize communities and craft new records of experience by which America could recognize and reckon with itself. As Biden looks to heal and rebuild civic and economic life in America, there are a lot of lessons he could take from the original new deal efforts – including the engagement of artists.

Indeed: We live in a moment when people discuss a green new deal, but it’s critical to remember that the original New Deal interwove arts and cultural investments with artists and humanists working in unexpected places throughout government. For instance, Lange was funded, not by, say, the National Endowment for the Arts, but by the Farm Security Administration – which was tasked with alleviating rural poverty.

I love Lange’s work: Three years ago, after reading her archival notes and looking at her contact sheets in The Oakland Museum, I set out, notebook in hand, to revisit the places in California Lange had photographed, to see what they looked like now. On that journey, during which I was writing poems and letters to Lange, I discovered telling tidbits. Near the fields in Imperial County where Lange photographed migrant carrot pickers in the late 1930s, there is now a migrant detention center which, according to its website, holds 782 people.

In Nipomo, where Lange photographed pea pickers in 1936, $2.1 million homes overlook industrial strawberry farms where day laborers pick crops for between $10 and $15 an hour. In Berkeley, California, where I attended high school and where Lange lived, tents line the freeway underpasses.

We live in a landscape of mass shelterlessness. It’s certain that if there were a Dorothea Lange at work today, she’d have a lot to witness.

From that department, she and some of the best photographers of her generation (Gordon Parks, Walker Evans, Lewis Hine) recorded vital chapters of American life – migration out of the Dust Bowl; the movement from sharecropping to industrial farming; the World War II labor effort; the stirrings of a postwar society. Even today this work offers us a crucial understanding: It makes America legible to Americans.

Let’s just imagine: What would it look like to put artists and humanists to work for the Department of the Interior, the Department of Transportation or the Department of Agriculture? What would it look like to build a cabinet-level position for the arts in America? What could artists do to help rebuild American communities, strengthen American civic life and document American lives today? In an era when we have felt painfully divided, how could our artists celebrate and document our diversity, build dialogue in our communities and help us see one another?

We might remember other vital records made throughout the New Deal years: how the Federal Writers Project funded writers like Zora Neale Hurston and Richard Wright to collect oral histories. How in Wisconsin, members of the Oneida Nation were employed to record the language and history of their community. How as part of the Federal Writers’ Project writers interviewed formerly enslaved people, crafting an archive of more than two thousand first-person narratives about slavery.

The Works Progress Administration funded murals and paintings in public buildings across America; they transformed national parks with gorgeous spaces like the Dee Wright Observatory that allow people to take in the splendor of American landscapes. Many of us still pass these gems daily. Spend time in line at the Peterborough Town Post Office in New Hampshire and you’ll rest your eyes on this beautiful town scene by Marguerite Zorach. Attend Berkeley High School, as I did, and learn to play jazz or dance or act in the high school’s community theater – a city resource, and a gift of the WPA.

The bad news about the pandemic is that it threatened our existing arts organizations, many of which have shuttered. It put American artists out of work. The good news is that we can keep building movements that ask that artists and humanists to be part of cultural and economic repair.

Paula Krebs, the executive director of the Modern Language Association, has imagined a world where humanists could be woven into health care organizations, and city governments and even police departments doing the important cultural work of helping to document and dismantle disparities.

Journalist and UCLA professor David Kipen is working with US Rep. Ted Lieu’s office to introduce a bill that would authorize a new federal writer’s project that would put journalists to work teaching writing and seeding documentary efforts in underserved communities, rural and urban alike.

The actors and writers-turned-labor-organizers at Be An #ArtsHero are working to craft a joint framework for relief and recovery called the DAWN Act (Defend Arts Workers Now) that would direct money for arts and culture businesses into all congressional districts and define such economic investments as drivers of small business, jobs, and tax revenue.

These thinkers posit cultural intervention as fundamental to restoring America’s economy and way of life. These efforts could promote both economic growth and civic healing. Next month, a consortium of philanthropic foundations will release a landmark report, authored by Metris Arts, that examines how community participation in the arts can increase social cohesion and strengthen health and well-being.

Yet Lange’s example also makes me wonder about the many corners of America that could use a witness, a voice, an advocate, a storyteller. What kind of witness does America need now? Surely the kind that can help us build a common purpose, see and care for one another and bind us together in a common civic life. All these years later, Lange (and the WPA artists she worked with) remind us that art can build up our national identity, can help us see both who we are and who we want to be.

There is something in Lange’s photographic gaze that insists upon our linked fates and our common dignity, and also gives us the chance to grapple and reckon with our national scars. This may be perhaps her biggest legacy. At the end of her life, looking back on her work, Lange remarked: “No country has ever closely scrutinized itself visually. … I know what we could make of it if people only thought we could dare look at ourselves.”

What should we make? What could we? What might it be to undertake that daring? In this moment, it feels once again urgent that we look.