On their way to and from the sprawling warehouse facility in Bessemer, Alabama, Amazon workers see union representatives holding signs encouraging them to vote “yes” for a union. But inside the facility, workers have frequently been pulled into meetings informing them of Amazon’s stance that a union is an unnecessary expense. Even when they sit on the toilet, they see anti-union signage on the bathroom stall.

For weeks, tension has been building at this warehouse in a small town in central Alabama ahead of a milestone vote, beginning this week, on whether to form what would be the first US union in Amazon’s nearly 27-year history.

In addition to waging online and offline pushes to combat the union effort, Amazon (AMZN) attempted to delay the vote by pressing for it to be held in-person, despite the pandemic, but the National Labor Relations Board rejected its arguments. The ballots started to be mailed to the homes of nearly 6,000 eligible warehouse workers Monday. They will have nearly two months to cast their votes.

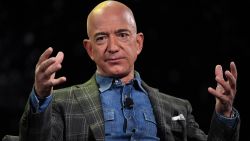

Even before a single vote was cast, the union push had garnered national attention and support from figures ranging from Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders to a group of 50 Congresspeople who sent a letter Friday urging Amazon’s outgoing CEO, Jeff Bezos, to “treat your employees as the critical asset they are, not as a threat to be neutralized or a cost to be minimized.” Warehouse workers at multiple Amazon facilities told CNN Business they are also paying close attention to see how the effort shakes out. As Jeffrey Hirsch, a labor law professor at the University of North Carolina, put it: “A whole lot of people are watching.”

An improbable union push partly fueled by the pandemic

The fact that the push to unionize has made it this far is improbable by several counts. Not only are the workers taking on the second-largest employer in the United Sates, whose business has soared in the face of the global pandemic, but these workers are based in the South, where union representation is lower than in other parts of the country. This effort was galvanized not just by a group of employees of the Amazon Bessemer facility but also with unionized workers from other local plants and facilities, including poultry workers, who are already represented by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, which advocated for their safety as poultry plants were hit hard by the virus.

Jennifer Bates, an employee-organizer at the Bessemer facility who has worked at Amazon since shortly after the warehouse opened last spring, said that making it to this point is a huge feat in and of itself. “We didn’t know how we’d reach so many people,” Bates, a learning ambassador who helps train other workers at the facility, told CNN Business. “Amazon is so huge. We have four floors and thousands of people in there. But we realized there were enough voices and enough issues. You can have complaints at any job but these were cries.”

Bates, who said she was represented by a union in a previous job, ticked off a list of issues that workers hope to improve with the help of union representation, including adequate break time, better procedures for filing and receiving responses to grievances, higher wages, as well as protection against Amazon wrongfully applying policies like social distancing to discipline workers.

In a statement to CNN Business in January regarding the union effort, Amazon spokesperson Heather Knox said, “we opened this site in March and since that time have created more than 5,000 full-time jobs in Bessemer, with average pay of $15.30 per hour, including full healthcare, vision and dental insurance, 50% 401(K) match from the first day on the job; in safe, innovative, inclusive environments, with training, continuing education, and long-term career growth.”

“We work hard to support our teams and more than 90% of associates at our Bessemer site say they would recommend Amazon as a good place to work to their friends,” added Knox. Over the past year, Amazon has repeatedly said safety is a priority as well as that it has a “zero tolerance for retaliation against employees who raise concerns.”

While the pandemic has been a boon for Amazon’s business, it has also been a factor behind a more general employee uprising. Workers at other facilities have expressed concerns about juggling the company’s obsession with productivity while maintaining social distancing and other pandemic-related precautions. Meanwhile, Amazon has been slowly peeling back some of its pandemic safety policies. The company discontinued its unlimited unpaid time off in May, as well as its $2 hourly wage bump and double overtime pay in June; it reinstated its “time off task” metric to track productivity of workers this fall. It is also reinstating daily stand-up meetings, which had been paused since the start of the pandemic, but will soon resume as “socially distanced small group stand-up meetings.”

Amazon has said it has made over 150 process updates to ensure the health and safety of its employees. The company, which continues to provide up to two weeks of paid time off for employees diagnosed with the coronavirus, has also given out two special bonuses to frontline workers since eliminating its pandemic-related wage bumps.

“The pandemic opened a lot of peoples’ eyes that workers really need a voice in their workplace in order to protect themselves,” said Stuart Appelbaum, president of RWDSU. “People are worried about their lives.”

At the same time, workers at Bessemer have been motivated by the ongoing racial justice movement, according to Appelbaum, who said roughly 85% of the workforce is Black. “People were inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement to stand up for their own rights and dignity,” Appelbaum said. “This campaign has been as much of a civil rights campaign as it has been a labor campaign. We’re talking about basic dignity for working women and men.”

It is unclear whether the union push will ultimately succeed. The Washington Post previously reported more than 3,000 Amazon workers had signed cards indicating support for the union, although given the company’s high turnover rate and the fact that some employees are seasonal, not all are still with the company.

“The most aggressive anti-union campaign I’ve seen”

While some Amazon workers are unionized in Europe, the company has so far fended off unions in the United States. A much smaller union election was held in 2014 at a Delaware warehouse, but resulted in workers rejecting the effort.

To counter the current effort at Bessemer, Amazon hired a former Republican member of the NLRB to help in its fight. It launched an anti-union website that warns against paying dues: “don’t buy that dinner, don’t buy those school supplies, don’t buy those gifts because you won’t have that almost $500 you paid in dues.” And it has conveyed its stance on unions by sending numerous text messages to workers, pulling them into one-on-one meetings on the warehouse floor and requiring them to attend group meetings every few shifts, workers and the union told CNN Business. (In a statement this week, Knox told CNN Business that Amazon has “provided education that helps employees understand the facts of joining a union.”)

The group meetings, also known as “captive audience” meetings, are required to cease 24 hours before an election; a company spokesperson previously told the Post that it will comply. According to Hirsch, Amazon’s insistence on holding an in-person election may have been due, at least in part, to the fact that the company can’t hold these meetings for the longer duration of the mail-in election period, potentially making it harder for the company to counter the union’s efforts to rally workers during this time.

Amazon spokesperson Maria Boschetti said in a statement to CNN Business last week that the company’s “goal” in pressing for an in-person election was to provide “the most fair and effective format to achieve maximum employee participation.”

All together, Appelbaum called it “the most aggressive anti-union campaign I’ve seen.”

Workers are now left to sort through the mixed messages. One Bessemer worker, who requested their name be withheld for fear of retribution, said they are puzzling over the financial impact of dues and the potential benefits of union representation.

The worker, who has not decided which way to vote yet, was initially attracted to the job because of the set hours and schedule, but now has concerns about pandemic safety measures inside the facility. “If you don’t want the people to have a union, you need to do everything [to address the concerns], or at least piece by piece,” the worker said.

Another Bessemer employee, Dawn Hoag, is adamant about how she’ll vote: “No.” She said she doesn’t feel like Amazon hid any of the conditions of the job when she was hired. “Not everybody is going to like having to work hard,” said Hoag, a seasonal process assistant who said she would request to transfer to a different facility if the union were to succeed. “I don’t see a purpose in me paying somebody else to fight my battles. I’ve always been told fight your own battles.”

Workers at other Amazon warehouses in the United State are paying attention to the outcome. At a Baltimore facility, Amazon associate Andre Goodin said he and several of his colleagues talk about the Alabama union vote “quite often, believe it or not.” Goodin, who has also previously worked a union job, said he believes there’s a host of things that could be potentially improved with the support of a union.

“We’re hearing from Amazon workers all over the country. I think that what has happened thus far is significant regardless of the outcome of the election,” said RWDSU’s Appelbaum. “It opens the door for more organizing in the future. It opens the door and shows you’re able to stand up to Amazon.”