Two years after humans last landed a probe on Mars, both the United States and China are launching missions to the red planet this month and setting up a new arena for their growing rivalry.

China’s Tianwen-1 blasted off around midday Thursday from Hainan Island in the country’s south, while NASA’s Perseverance rover is scheduled to launch on July 30. Both probes are expected to reach Mars in February 2021.

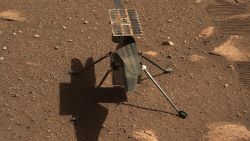

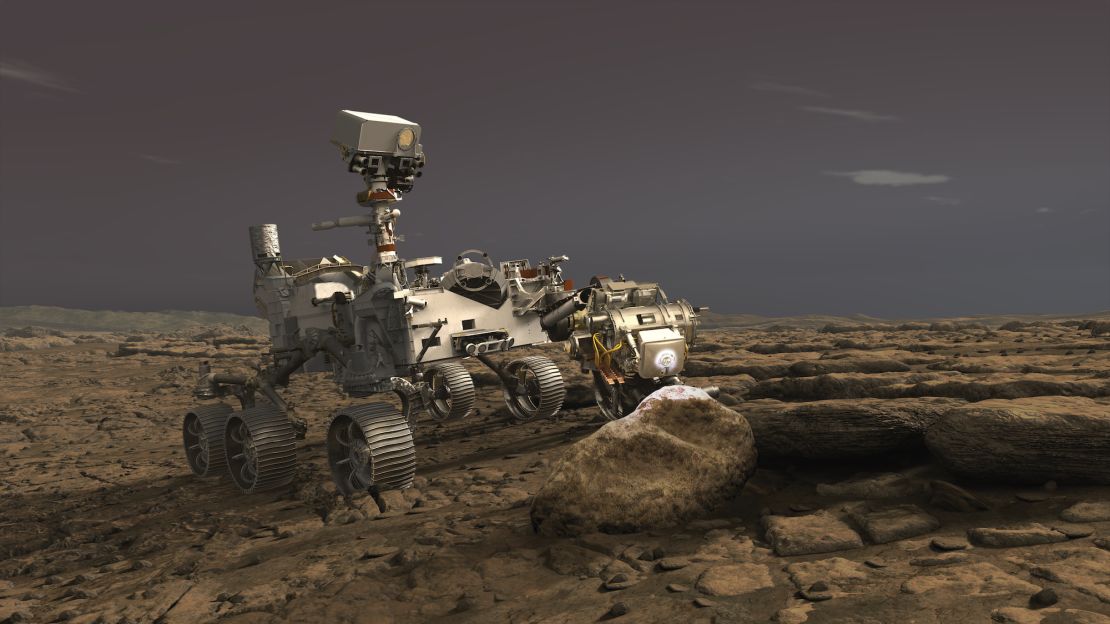

Perseverance aims to answer questions about the potential for life on Mars, including seeking signs of habitable conditions in the planet’s ancient past and looking for evidence of microbial life. The rover has a drill which can be used to collect core samples from rocks and set them aside to potentially be collected and examined by a later mission.

If successful, Perseverance will be the seventh probe NASA has landed on Mars, and the fourth rover. Curiosity, which landed on the red planet in 2012, is still sending back data about the Martian surface.

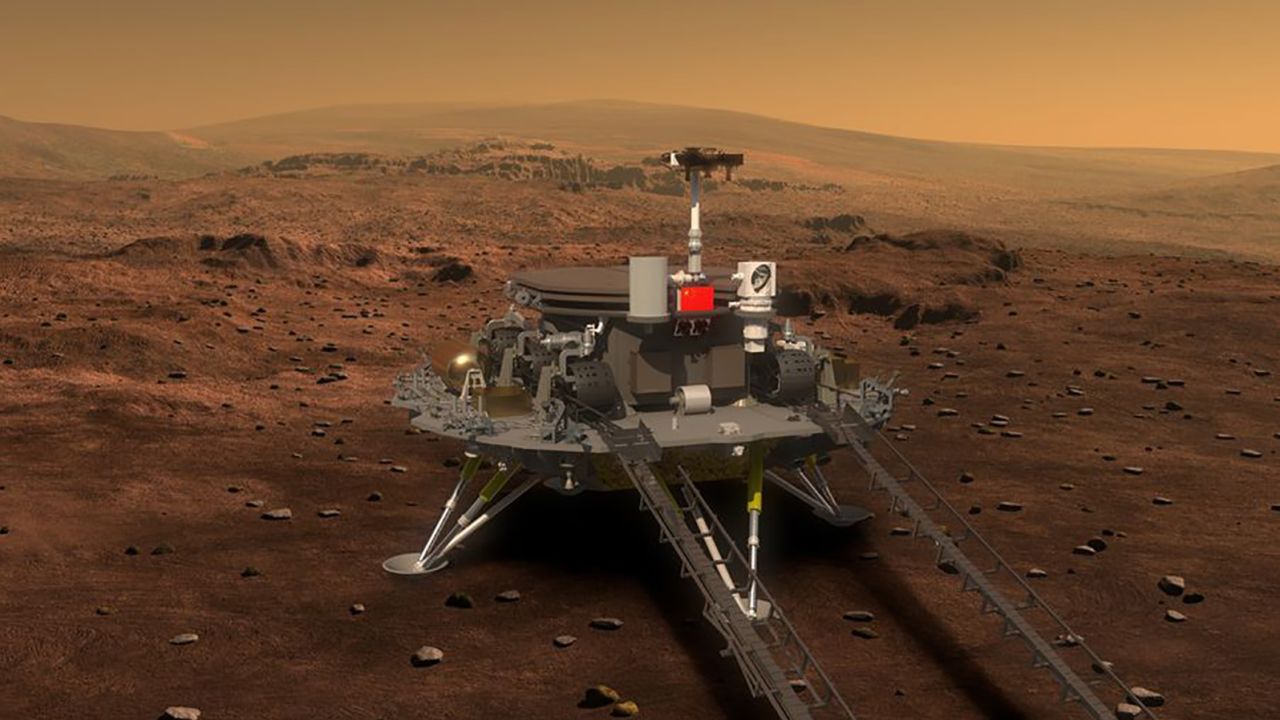

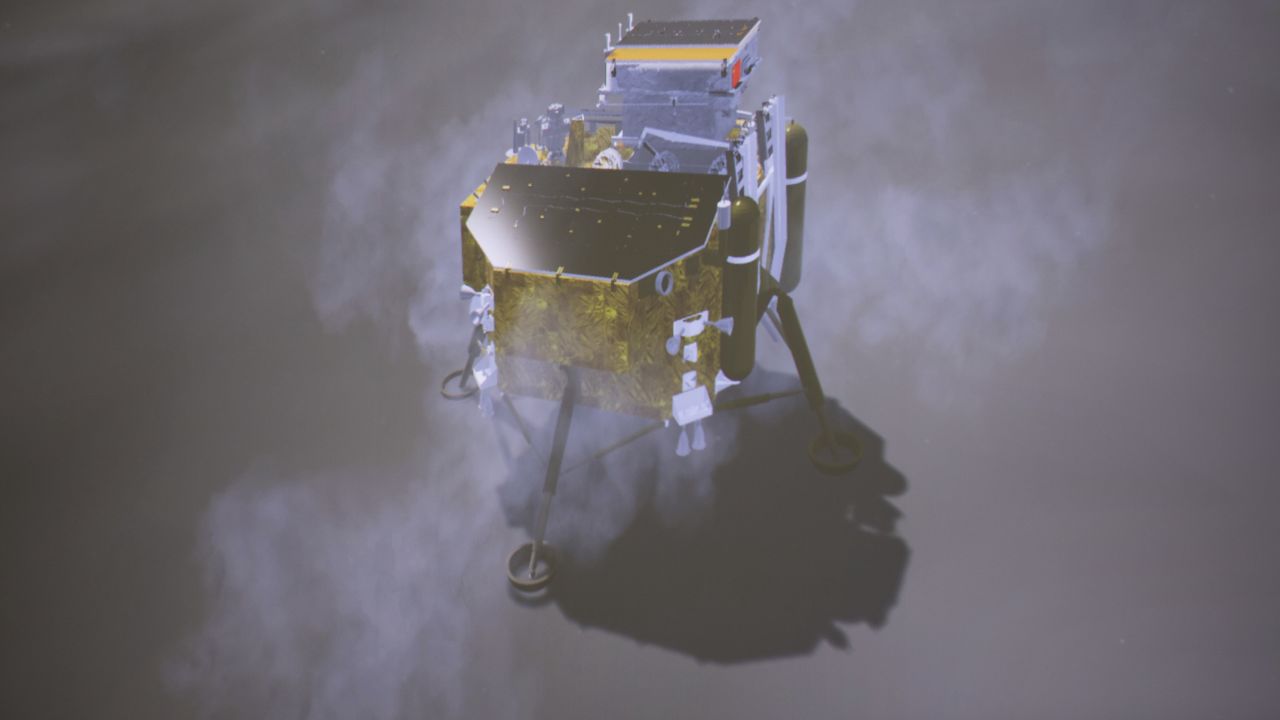

Tianwen-1, whose name means “Quest for Heavenly Truth,” is China’s first mission to Mars. The probe will orbit the planet before landing a rover on the surface, with the hope that it can gather important information about the Martian soil, geological structure, environment, atmosphere, and search for signs of water.

In a paper last week, the scientific team behind Tianwen-1 said the probe is “going to orbit, land and release a rover all on the very first try, and coordinate observations with an orbiter. No planetary missions have ever been implemented in this way.”

By contrast, NASA sent multiple orbiters to Mars before ever attempting a landing. Pulling off the landing is a far more difficult task.

“If successful, it would signify a major technical breakthrough,” the Chinese team wrote in the journal Nature.

Space race

In their paper, the Tianwen-1 scientists noted the chance for international collaboration to “advance our knowledge of Mars to an unprecedented level.” It’s not only their own probe and NASA’s that are arriving at the planet next year, but also the United Arab Emirates’ Hope Probe, which blasted off on Sunday. The Hope Probe is the Arab world’s first interplanetary mission.

Scientists working for NASA and China’s space agency have enjoyed a collegiate relationship in the past. They’ve collaborated on the International Space Station, and congratulated each other on successful missions, such as China’s landing of a probe on the far side of the Moon, the first country to ever do so.

But for all the insistence of those involved to the contrary, the space race is inescapably political. NASA’s early missions, particularly its historic landing of humans on the Moon in 1969, were fueled by the Cold War rivalry between Washington and the Soviet Union.

Beijing, for its part, is well aware of the potential prestige it could gain by outstripping the US in space. If Tianwen-1 is successful, it has plans to eventually send a manned mission to Mars.

Under President Xi Jinping, China has invested billions of dollars in building up its space program, even as it asserted its influence back on Earth more aggressively and pursued the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

Space has been singled out by the Chinese government in its 13th Five Year Plan as a research priority, especially deep space explorations and in-orbit space craft. As well as the Mars mission, Beijing is also planning to launch a permanent space station by 2022, and is looking at sending a manned probe to the Moon possibly in the 2030s.

This program is building on the findings from China’s recent missions to the Moon, particularly the Yutu rovers, the first of which had to abandon its mission half way into the three-month timescale due to a breakdown. Yutu-2, which landed on the far-side of the Moon last year, has been a huge success.

“Our overall goal is that, by around 2030, China will be among the major space powers of the world,” Wu Yanhua, deputy chief of the National Space Administration, said in 2016.

Mission to Mars

China came late to the space race. And while it has made incredible strides in recent decades, outpacing NASA — at least in terms of bragging rights, if not scientifically — would require something spectacular, like landing a human on Mars.

But there is a reason that since 1972, all space exploration has been carried out by robots. Not only are they cheaper, they’re also far longer-lasting and more durable: No country wants to be the first to have an astronaut die on another planet.

Landing robotic probes on Mars is hard enough, given the planet’s atmospheric conditions. Getting a human there safely might be next to impossible.

But this hasn’t stopped politicians speculating about a manned mission to the red planet. Early in his term, US President Donald Trump authorized NASA to “lead an innovative space exploration program to send American astronauts back to the moon, and eventually Mars.”

Trump also created Space Force, a new branch of the armed services. At an unveiling of the organization’s flag earlier this year, the US leader said that “space is going to be the future. Both in terms of defense and offense and so many other things.”

“Already, from what I’m hearing and based on reports, we are now the leader in space,” he added.

Nor is Washington about to let China overtake it. Last year, when CNN quoted Joan Johnson-Freese, a professor at the US Naval War College, saying the “odds of the next voice transmission from the moon being in Mandarin are high,” Trump-appointed NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine retorted, “Hmmm, our astronauts speak English.”