Cases of potentially dangerous foodborne illnesses caused by common bacteria in the United States food supply increased during 2019 compared to the previous three years, according to a new report released Thursday by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC estimated that 48 million people get sick from various foodborne illnesses in the United States each year. Of those, approximately 128,000 are hospitalized and 3,000 die.

Experts stressed, however, that the data does not apply to the current pandemic of Covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.

“There’s no evidence right now to support transmission of Covid-19 by our food supply,” said Dr. Patricia Griffin, chief of the CDC’s enteric, or intestinal, diseases epidemiology branch.

“Covid-19 is caused by a different pathogen, with a different mode of transmission, different biology, different epidemiology,” said food safety expert Benjamin Chapman, a professor in the department of agricultural and human sciences at North Carolina State University, who was not involved in the report.

“The foodborne pathogens that we’re talking about here are ones that we have identified for years that cause millions and millions of illnesses from consuming food. We don’t have any examples or any history of Covid-19 being transmitted by food at all,” Chapman said.

A dangerous trend continues

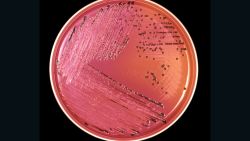

The report analyzed data from the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) and found sicknesses caused by Campylobacter, Cyclospora, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), Vibrio and Yersinia increased in 2019 as compared to the three-year period between 2016 and 2018.

At the same time, cases of Listeria, Salmonella and Shigella failed to decline during the same time period, despite continued efforts over the past decade to stop the spread of dangerous pathogens in the nation’s food supply.

This means that the United States will not meet its food safety targets for “Healthy People 2020,” a government program begun in 2010 with the goal of achieving “high-quality, longer lives free of preventable disease, disability, injury and premature death.”

“We’ve been stalled in many aspects of preventing foodborne disease for many years,” Griffin said. “Our systems allow pathogens to enter our food supply and we’re not doing everything we can to get them out. We need to have better control measures at all levels.”

Chapman agreed: “This is not a new problem,” he said. “Food safety issues continue to occur along the food chain, from farms to processing plants to grocery stores to restaurants and the home.”

“We spent a lot of time on trying to change behaviors and there are a lot of good things that are happening, but the actual payoff for public health is in the reduction of illness, and we’re just not seeing it.”

Tracking eight major foodborne illnesses

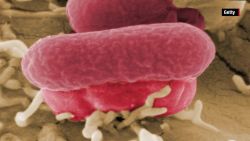

The most common bacterial cause of diarrhea in the United States is Campylobacter, affecting about 1.5 million Americans every year. The diarrhea is often bloody, with stomach cramps and fever.

Unfortunately, it’s super easy to catch. “A single drop of juice from raw chicken can contain enough bacteria to infect someone,” the CDC said.

Infections often occur when a cutting board that has been used to cut and prepare raw chicken isn’t washed before it’s used to prepare other raw or lightly cooked foods such as salad or fruit.

Three other extremely common foodborne illnesses are Salmonella, Shigella and Listeria. All cause bloody diarrhea, fever and stomach cramps.

Listeriosis is a serious infection which primarily affects pregnant women, newborns, older adults and people with weakened immune systems, according to the CDC. Typically mild during pregnancy, it can cause severe disease in a developing or newborn baby.

Older people and those with weakened immune systems can also develop severe infections of the bloodstream or brain. Outbreaks are often linked to dairy products such as soft cheeses and ice cream or produce such as celery, sprouts and cantaloupe.

Salmonella bacteria live in the intestines of people and animals and can be ingested by eating contaminated water or food or touching infected animals or their feces. The bacteria is often found in poultry and eggs, but it can grow in many foods, including pork, sprouts, spinach, lettuce and other vegetables and fruits, and even in processed foods.

The CDC estimated there are 1.35 million Salmonella infections each year in the US, causing 26,500 hospitalizations and 420 deaths, but actual cases are probably much higher. For every person with Salmonella confirmed by a laboratory test, the CDC said there could be 30 more that are not reported.

Shigella germs are in the stool of sick people while they have diarrhea and for up to a week or two after. The bacteria are very contagious, and outbreaks are often associated with childcare settings, swimming pools and schools. The CDC estimated Shigella causes about 450,000 cases of diarrhea annually.

The tiny one-celled parasite Cyclospora causes vomiting, body aches, headache, fever and a form of watery diarrhea, with “frequent, sometimes explosive, bowel movements,” according to the CDC. The parasite is common in tropical or subtropical regions of the world and outbreaks have been linked to various types of imported fresh produce.

Vibriosis causes watery or bloody diarrhea and is responsible for about 100 deaths and 80,000 illnesses each year. People are infected by exposing a wound to seawater or eating raw or undercooked seafood such as oysters, according to the CDC.

Another illness with bloody diarrhea is yersiniosis, typically caused by eating raw or undercooked pork. It affects mostly children and causes 17,000 illnesses, 640 hospitalizations and 35 deaths in the United States every year.

To protect you and your family from foodborne illness at home, the CDC lists the following food safety precautions:

- “Wash your hands and work surfaces before, during and after preparing food.

- Separate raw meat, poultry, seafood and eggs from ready-to-eat foods. Use separate cutting boards and keep raw meat away from other foods in your shopping cart and refrigerator.

- Cook food to the right internal temperature to kill harmful bacteria. Use a food thermometer.

- Keep your refrigerator at 40 F or below. Refrigerate leftovers within two hours of cooking (or within one hour if food is exposed to a temperature above 90 F, like in a hot car).”

Change is possible

It is possible to improve the safety of our food supply. Griffin pointed to the success of major fast food restaurants in reducing E. coli O157:H7 in the food supply after the Jack-in-the-Box outbreak of 1993.

“The fast food companies got tired of being implicated in the outbreaks,” she said. “And so they told their meat suppliers that they had to get that pathogen out of the meat.”

That could happen again today, Griffin said.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“Many of the bigger retail stores can use their economic pull to say their food has to be of a certain microbiologic quality, and consumers can also vote with their feet. So even though we’ve been stalled for a while, success is clearly possible,” she said.

In the US, poultry farmers began vaccinating chickens against one of the most common subtypes of Salmonella, called typhimurium. It was the only subtype to see a decline in the 2019 report.

“And probably as a result of that, you’re seeing many fewer typhimurium cases in humans, so maybe it could be extended to other serotypes of Salmonella,” Griffin said.

When such efforts are backed by government intervention, change can even be permanent. When the United Kingdom was faced with a 170% increase of Salmonella enterica during the ’80s, it fought back with government legislation, food safety information for the public and a poultry vaccination program by breeders. The number of cases plummeted and has remained low.

It’s going to take new thinking and a concerted effort by all to combat the problem, the report said.

“It’s not just one area,” Chapman said. “We need more vigilance on the farm level. We need better technology in production and distribution. It’s consumer habits. We need to rethink the methods we have been looking at or do them in a smarter and better way. It really is: How do we get people to care about this?”