Editor’s Note: In this weekly column “Cross-Exam,” Elie Honig, a CNN legal analyst and former federal and state prosecutor, gives his take on the latest legal news. Post your questions below. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN. Watch Honig answer reader questions on “CNN Newsroom with Ana Cabrera” at 5:40 p.m. ET Sundays.

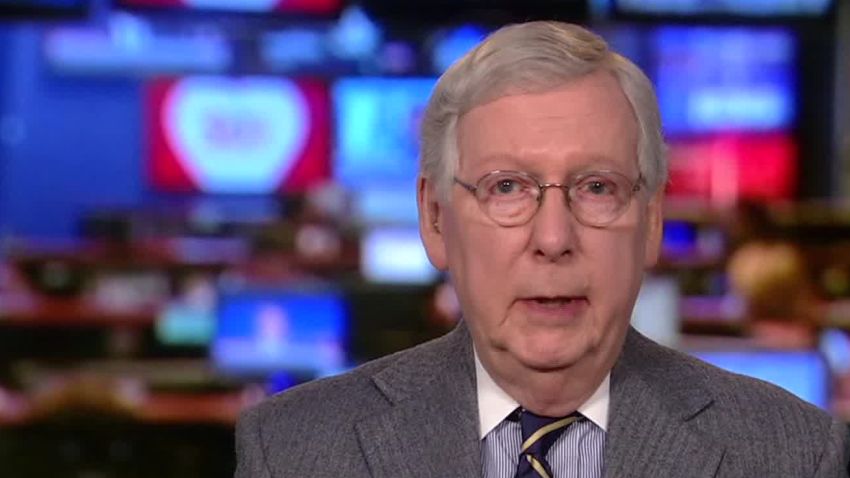

Give Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell this much: at least he’s open and transparent about his plan to rig the upcoming Senate impeachment trial of President Donald Trump. McConnell – who will serve as both judge (in his capacity as majority leader to set the procedure before trial) and juror (as one of the 100 senators who will vote to convict or acquit Trump) – came right out and said that he will work “in total coordination with the White House counsel.” McConnell’s disdain for even the appearance of a fair process is so pointed that it seems his end goal is to de-legitimize the upcoming trial before it begins.

McConnell is not the only future impeachment juror to have made rash statements about the upcoming trial. Senator Lindsey Graham, abandoning all pretext of impartiality, proudly declared that he’s “not trying to pretend to be a fair juror here.” And this tendency to pre-judge crosses party lines.

For example, Elizabeth Warren has stated that what Trump “has done is an impeachable offense, and he should be impeached.”

It is bad for the process when senators of either party publicly undermine their obligation to be impartial. But McConnell’s conduct is worse than that. Each senator is one vote out of 100, but McConnell’s pronouncement that he will totally coordinate with the White House is destructive to the underlying constitutional process we are about to see unfold.

An impeachment trial is different in many respects from a criminal trial, but the criminal process provides a useful point of reference. If a person in McConnell’s position – judge or juror – tried to coordinate with a party to a criminal case, he would be thrown off the case, disciplined and potentially prosecuted for obstruction of justice. While this isn’t a criminal case, McConnell’s comments show his disregard for the weight of the moment.

It is hard to miss that McConnell’s pronouncement comes with a note of glee. Far from being secretive or apologetic about his coordination with the White House, he has come right out and boasted about it. It seems his cynical bottom line goal is to de-legitimize the process – to promote the broad public view that the Senate trial is not a meaningful truth-finding exercise but rather empty political theater. His remarks seem designed to elicit a dismayed shake of the head and then a “what are you gonna do?” shrug from the populace. McConnell likely will get what he wants – a quick acquittal of Trump – but only at the long-term cost of public confidence in the integrity of our political and legal processes.

Now, your questions

Vignesh (New Jersey): What is the significance of the Supreme Court agreeing to hear the cases relating to Trump’s tax returns?

The Supreme Court last week granted certiorari (meaning, in plain English, it “agreed to review”) Trump’s efforts to block disclosure of his tax returns. The court consolidated three separate cases for its consideration – two involving congressional subpoenas and a third involving a subpoena from the Manhattan district attorney’s office, all served on private companies handling Trump’s personal finances.

This is a temporary win for Trump. In all three cases, both the trial-level federal district courts and the intermediate level courts of appeals have ruled against Trump and upheld the subpoenas. Had the Supreme Court declined to review the cases, those courts of appeals rulings would have become final, and Trump’s tax returns would have been disclosed to Congress and the district attorney.

But, longer term, the ruling might prove to be more of a reprieve for Trump than a win. It would take quite a reversal for the Supreme Court to find that all the lower courts got it wrong – though, as the nation’s highest arbiter, the court certainly can and does overturn lower courts as it sees fit.

Some speculate that it is a good sign for Trump that the Supreme Court agreed to take the case. The court requires four votes (out of nine justices) to grant review. So, the thinking might go, we can assume at least four justices felt a need to take the cases and prevent the lower court rulings from taking effect, signaling an inclination to reverse.

On the other hand, it could be that four (or more) justices voted to take the cases because they recognized the enormous constitutional stakes presented by an inter-branch dispute between Congress and the White House (in the two Congressional cases) and between a state prosecutor and the federal executive branch (in the Manhattan district attorney office’s case).

We will get a ruling from the court by June 2020 at the latest. The decision therefore could hit right in the heart of presidential campaign season. Depending on the outcome, the ruling could be either an embarrassing rebuke (and potentially worse) to Trump, or a vindication of his long-claimed right to withhold his personal financial information from Congress and prosecutors.

Tom (Colorado): Will the representatives and senators vote on each article of impeachment separately, or will there be one vote for both articles?

When the full House votes later this week on the two pending articles of impeachment against Trump, each member will vote separately on each article. Similarly, at the conclusion of a Senate trial, each Senator will vote yes or no on each article.

So it won’t be an all-or-nothing proposition. Some members of Congress might split their votes – likely with some members voting “yes” on Article I (Abuse of Power relating to Ukraine) but “no” on Article II (Obstruction of Congress), reasoning that Trump’s defiance of congressional subpoenas is less serious or more defensible than his attempt to pressure Ukraine to investigate his political rivals.

While not likely, we could end up with a split outcome, with one article passing and the other failing in the House. That type of split decision happened in the Bill Clinton impeachment in 1998. The House Judiciary Committee approved four articles of impeachment, but the full House approved two while rejecting two others.

Gary (New York): Who serves as the defense lawyers and prosecutors in a Senate impeachment trial?

The President can hire any attorneys who are willing to put forward his defense. During the 1999 Clinton impeachment trial, a team comprised of White House counsel and private attorneys defended the President on the Senate floor. Similarly here, it appears Trump will go with White House Counsel Pat Cipollone as his lead attorney, plus reportedly outside attorneys including former Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi.

The case against Trump will be presented on the Senate floor by a team of House Managers – members of the House of Representatives appointed by the House itself (with Speaker Nancy Pelosi having the most powerful say). The House has not yet named its Managers, but it seems virtually certain that Rep. Adam Schiff will be part of the team, after leading the House Intelligence Committee’s investigation. Other potential House Managers include Rep. Eric Swalwell (a former prosecutor), Rep. Val Demings (a former police chief who sits on both the House Intelligence and Judiciary Committees), Rep. Jamie Raskin (a former constitutional law professor) and Rep. Ted Lieu (a former military judge advocate general).

Three questions to watch:

1. Will any House Republicans vote to impeach, and how many Democrats will vote not to impeach?

2. What strategy will Trump pursue as he prepares for a Senate trial?

3. Will Attorney General William Barr take official steps to undermine the Inspector General’s conclusions about the Russia investigation?