An Alabama state commission acted Friday to protect the schooner Clotilda, believed to be the last ship to bring enslaved people to the United States from Africa.

The Alabama Historical Commission filed a claim under admiralty, or maritime law, in US District Court in Mobile. The claim will ensure that the Clotilda, which sank in the Mobile River in 1860, remains a publicly owned resource, the commission said in a statement.

“It carries a story and an obligation to meet every opportunity to plan for its safeguarding,” said Lisa Jones, the commission’s executive director. “AHC is laying the groundwork for ongoing efforts to not only ensure the Clotilda’s immediate assessment, but to also establish pathways for its longevity.”

The commission said a key benefit of an admiralty claim involves retrieving any artifacts that have been taken from the ship and will help prevent against future attempts to take artifacts from it.

“By preserving the Clotilda, Alabama has the opportunity to preserve a piece of history,” Gov. Kay Ivey said in the statement. “It is a prime example of an artifact that deserves our respect and remembrance.”

The Roots of Africatown

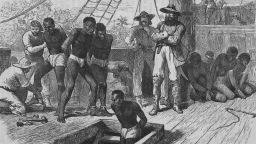

Though importing slaves had been illegal for decades in 1860, the schooner brought 110 slaves from what is now Benin across the Atlantic, slipping past federal authorities to Mobile.

The ship’s captain, William Foster, acting on behalf of Alabama plantation owner Timothy Meaher, navigated the Clotilda up the Spanish River and transferred the slaves to a riverboat. Foster then burned the ship, sinking it upriver.

Many of the ship’s slaves, freed five years later at the end of the Civil War, settled a community north of downtown Mobile that became known as Africatown.

Descendants of the original slaves still live in the area. The descendants will be consulted on decisions about the future of the Clotilda.

‘Painstaking and difficult’ work

Interest in finding the Clotilda reignited in January 2018 after AL.com reporter Ben Raines discovered the remains of a ship near Mobile. Experts and volunteers got to work to determine whether the remains really belonged to the last known slave ship.

It was determined this shipwreck wasn’t the Clotilda — the remains were too big — but everyone agreed to keep searching.

The state announced last May that the wreck in the Mobile River had been positively identified as the Clotilda. The commission is working with multiple organizations to assess the ship’s condition before further excavation is performed.

“This kind of archaeological work is painstaking and difficult under any circumstances, but the physical conditions of this particular site — zero visibility, high currents and potential entanglements — made this an especially difficult shipwreck to work on,” said Dave Conlin, a founding member of Slave Works Project and head of the National Park Service’s Submerged Resources Center.

CNN’s Doug Criss contributed to this report.