Editor’s Note: In this weekly column “Cross-exam,” Elie Honig, a former federal and state prosecutor and CNN legal analyst, gives his take on the latest legal news and answers questions from readers. Post your questions below. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion articles on CNN. Watch Honig answer reader questions on “CNN Newsroom” at 5:40 p.m. ET Sundays.

This week, the House Judiciary Committee held its first hearing designed to examine the findings of special counsel Robert Mueller. While the hearing drew the ire of President Donald Trump, in the end, he had little cause for concern – it was a dud.

The proceeding smacked of spectacle over substance and shed little light on Mueller’s findings. If the hearing served any useful purpose, it was to highlight the need for the American public and Congress to hear directly from Mueller and the people who directly witnessed Trump’s alleged over-the-top efforts to obstruct justice.

Ultimately, the hearing yielded no new facts (nor could it have, given that no firsthand witnesses testified). And no member of Congress changed position on impeachment.

The hearing did feature insightful testimony from former federal prosecutors who explained that Trump’s conduct would have gotten anybody other than the sitting President indicted for obstruction of justice. But the star witness was John Dean, former White House counsel under President Richard Nixon, who participated in the Watergate coverup and later stunned the nation by testifying publicly about Nixon’s participation in it. Dean’s testimony produced some pointed exchanges with committee members and provided valuable historical context, but nothing that will move the needle.

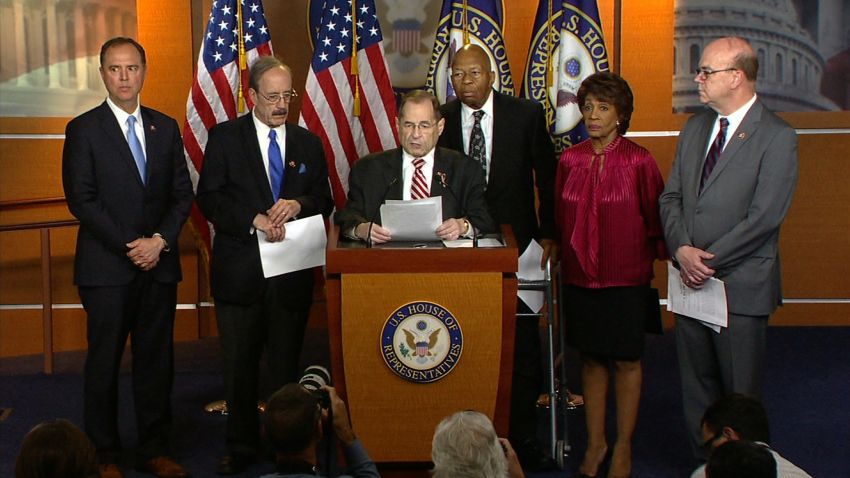

The problem was the committee had the wrong former White House counsel: it had Nixon’s, but it needed Trump’s. The hearing highlighted just how vital it is that House Judiciary Chairman Jerrold Nadler obtain testimony from the real witnesses. Neither Congress nor the public will be swayed until they hear from people who were in the room when Trump tried to derail Mueller’s investigation.

And it seems those witnesses will not testify without a fight. Former White House counsel Don McGahn and former White House aides Hope Hicks and Annie Donaldson already have followed directions from the White House to defy subpoenas, and there’s every reason to believe other key firsthand witnesses to obstruction – including former Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski, former Attorney General Jeff Sessions and former White House deputy Rick Dearborn – will receive and obey the same orders.

Nadler needs to get serious – and fast. Subpoena key witnesses with firsthand knowledge of Trump’s conduct. If a witness defies a subpoena, file suit in federal courts to compel compliance. (Tuesday’s House vote gave Nadler the crucial power to bring subpoena disputes to the courts for enforcement). And, to avoid death by slow-play, Nadler needs to request that the courts expedite their rulings.

What’s the fear here? So far, Congress has brought two lawsuits in federal court to enforce subpoenas, won them both and obtained lightning-quick decisions both times. It’s time for Nadler to abandon the showmanship and take decisive action to compel testimony from the people who bore firsthand witness to Trump’s obstruction of justice. Only then will Congress meet its constitutional duty to gather facts necessary to hold the President accountable.

Now, your questions

Harry, Colorado: If the House impeaches the President on obstruction of justice, and the Senate acquits, can he still be charged with obstruction in criminal court after he leaves office?

Yes, a president can be charged criminally after leaving office, even if he has been impeached by the House and acquitted by the Senate. Conversely, even if a president is impeached and then convicted by the Senate and removed from office, there is no guarantee that he will be charged or convicted in a criminal court.

The Constitution provides that, even where impeachment results in removal from office, “the party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to indictment, trial, judgment and punishment.” Indeed, impeachment and criminal charges are distinct concepts with distinct purposes and mechanisms. Impeachment is a political remedy for abuse of power designed to remove a person from office; indictment and criminal charges punish a person for breaking the law with imprisonment or other penalties.

According to Politico, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi reportedly stated of Trump, “I don’t want to see him impeached. I want to see him in prison,” suggesting that an unsuccessful impeachment effort resulting in acquittal in the Senate undermines or forecloses potential future criminal charges. (She declined to confirm the comment to CNN on Tuesday). As a legal matter, that is simply incorrect. As a political matter, however, a criminal charge following unsuccessful impeachment might look like overkill or piling on, which could make a prosecutor more reluctant to bring criminal charges.

Larry, California: If the President is impeached by the House and found guilty by the Senate, is he or she prevented from running for office in the future? Could Trump be impeached, removed from office and then run again in 2020?

The Constitution states that a judgment of impeachment results in “removal from office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust or profit under the United States.” Thus, on its face, the Constitution appears to provide that if a person is impeached by the House, convicted by the Senate and removed from office, he also can be disqualified from holding office in the future.

But some legal scholars have argued that the Senate must vote separately on (1) removal from office and (2) disqualification from holding future office. Looking at historical precedent, the Senate has at least twice voted to remove federal judges, and then separately voted on whether to disqualify the judges from holding office in the future. And while a two-thirds vote of the Senate is constitutionally required for removal, the Senate has used a lower simple-majority vote standard in prior cases of disqualification. So, if the Senate did vote to convict and remove the President, it likely would also vote separately on whether to bar him from holding office again in the future.

Vikki, Illinois: I can understand why Democrats are hesitant to impeach the President and then send it to the Senate for a vote on conviction – given that Republicans control the Senate. Instead, could the House conduct a formal impeachment investigation and then vote to censure the President?

Constitutional law scholar Laurence Tribe recently proposed a similar procedure designed to create a formal record of Trump’s conduct in the Democratic-controlled House without sending the matter to the Republican-controlled Senate for what many see as an inevitable party-line vote of acquittal.

Under Tribe’s proposal, the House would hold an impeachment investigation, affording Trump the right to mount a defense. The House would then vote on a resolution proclaiming the President impeachable – which Tribe calls “far stronger than a mere censure” – but would not forward the matter to the Senate for a formal vote on removal from office.

Tribe’s proposal has some merit. It would promote public understanding of Trump’s conduct and create an important historical record. As Tribe writes, the House would act “consistent with its overriding obligation to establish that no president is above the law … without setting the dangerous precedent that there are no limits to what a corrupt president can get away with as long as he has a compliant Senate to back him.”

I see two arguments against Tribe’s approach. First, it is an end-run around the process set forth in the Constitution: the House votes to impeach, then the Senate holds a trial and votes either to acquit or to convict and remove from office. Second, Tribe’s approach is more sizzle than steak. While the House would go through the motions, the end result (at most) would be a sternly-worded resolution condemning the President, but without actual penalty (such as removal from office).

Frank, Washington: Can the Department of Justice policy against indicting a sitting president be changed by Congress?

Theoretically yes, but practically no. In theory, Congress could pass a law declaring that a sitting president is subject to indictment, but the bill ultimately would require the signature of the very person who stands to lose the most – the President himself. Not likely.

Even if Congress passed such a bill and the President signed it, Congress cannot direct the Justice Department to indict a specific person. Such a law is called a “bill of attainder,” which the Constitution forbids. The decision whether (or not) to indict always sits in the Executive Branch, specifically the Justice Department.

At most, a new law might prompt the Justice Department to reassess or withdraw its policy. Even if the department changed its policy and decided to indict, the President likely would argue in court that it is unconstitutional for the Justice Department to indict a sitting president – as articulated in the memo that underpins the current nonindictment policy. In all, it is exceedingly unlikely that legislation can or will change the Justice Department policy against indicting a sitting President.

Three questions to watch:

1) Now that Nadler has authority to bring subpoena disputes into court for enforcement, will he use that power to try to compel McGahn, Hicks and others to testify?

2) If Pelosi currently thinks or begins to think that Trump should be in prison, how will she reconcile that view with her current position that impeachment is not yet appropriate?

3) Will the deal hold between the Justice Department and Nadler, allowing Congress to review some of the evidence underlying the Mueller report, and will it set an example for future compromises?