Editor’s Note: Tess Taylor is the author of the poetry collections “Work & Days” and “The Forage House.” The views expressed in this commentary are solely hers. View more opinion articles on CNN.

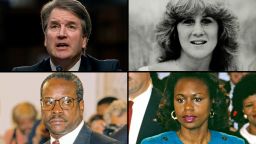

Like so many women, I remember. I remember the couch I was sitting on watching Anita Hill speak to the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1991. I remember the horrible feeling of watching that row of white male senators question – and disbelieve – her. I remember my own depression, disbelief and dismay: feeling my throat tighten, furious and sad to watch this woman’s account of her sexual harassment being minimized and dismissed. I remember a mix of sadness, shame, horror. Was this what would happen to me if I were ambitious, but also spoke up for myself? Was this what would happen to my friends?

Like many women, I also remember being grateful, amazed by her bravery, by the work she was doing for us. I remember learning the Muriel Rukeyser quote:

“What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life?

“The world would split open.”

I remember feeling that Hill was willing to crack the world open a little farther by sharing such a personal pain on behalf of us all. I remember understanding how the personal was political, how she was breaking a political silence that surrounds victims of sexual harassment and assault in shame. I remember that she was speaking truth to power. I remember my awe that she would tell these intimate sad truths to demand and insist that what happened to her be considered, be valued, be honored, be part of the record. I remember how it felt important to insist this mattered.

I remember learning the term “sexual harassment,” that it was something we could claim and we could own. And I remember also feeling that Anita Hill was insisting on something better for all women and girls — that she was giving us new words, new rights. We had the right to demand something better for our workplaces, for our childhoods, for our schools, for our bodies. I remember also knowing that this was not a given but that we would need to demand it. We had come some way as women, but we had so far to go. I remember knowing that it didn’t matter what we said if we wouldn’t be listened to. I knew that room full of white male senators doing the questioning would have to change. Like many women, I felt then that it was our job to be the change, that our generation had to change it.

I was 15, and I was galvanized. My friends and I were ready for a new wave of feminism. We were ready to be activists. We formed a high school chapter of the National Organization for Women. We tried to pick up the mantle of activism from our mothers. We worked to get Dianne Feinstein in office. We organized a sexual harassment survey to find out how women in our high school felt treated. Before the internet, we spent long nights with paper records, tallying our stories, joining our voices, finding ways to amplify our truths. We worked for months to demand change at our school: We reported that we had been made to feel uncomfortable on our own campus, and we gathered the statistics that none of us were alone. Many of us had been touched or groped or grabbed against our will. One of the school’s dark hallways was often where it happened, and there were problems in a certain classroom. We were fledgling feminists. We were ready to take on the system.

I’d like to say that we stayed galvanized, that the changes were permanent, but systems of oppression are tenacious, the work of activism draining, institutions slow to change. Later, I attended a college where women felt they had to whisper what each knew about men who’d committed rape on campus; to warn others who might be a little bit “rapey.” Some of us cried in one another’s bedrooms. Some of us felt sure it was our fault. Some of us left school rather than press charges. When those of us who had been assaulted came forward, we were told we could press charges, but told it was really such a lot of hassle: Wouldn’t we be more comfortable being silent? Also, were we sure? Also, was speaking worth it? Also, wasn’t that just how boys were?

This was the game. Important people seemed to say: Your voice won’t matter much, so suck it up and take it. Maybe they were right. Maybe the thing was to accommodate the power, and work to change it later. Maybe the thing was to get quiet and low and assume things would never change. Maybe silence was the best pragmatism there was. We doubted ourselves. And: We wanted to get by. We wanted to succeed.

Maybe we hoped we could change things later. Maybe we hoped we could skirt by without the damage damaging us. And: We learned to be survivors. We learned who we could tell and who we couldn’t. Later, when some of us went on to graduate school and our advisers asked us for sexual favors; or some of us went on the job market and were asked for sexual favors; or when people who were offering us jobs also wanted to grope us and found ways to corner us, we did not always speak out. Some of us stopped feeling that we could speak out. Some of us began to feel that rocking the boat would simply dump us in the water. When we went to the university that employed us, we were told politely that perhaps it would be better for us to be silent. We were reminded that we had comparatively little power; that we would derail our own careers by complaining.

Like so many women: I remember. I remember feeling like it would be easier to push it under the rug. I remember who did what and when. I remember trying to calculate how to survive a situation, how to keep going; how to find a mentor who’d simply mentor; how to keep pushing forward in a culture that I knew well would prefer to discredit me, keep me powerless, keep me silent. Sometimes I tally the losses, and sometimes I feel like it is wiser not to, for fear I will be too angry.

Thursday morning after dropping off my young daughter at school, I turned on the radio to hear Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony. I had to pull over to the side of the road to cry. I cried because I believe her. I cried because like many women, I know that story very well: Maybe a different bedroom, a different drunk, a different violence or violation, a different bad deal, a different indifferent laughter. I cried because I am angry. I cried because I want a world where my daughter trusts her voice and her stories will be listened to. I want a world where my daughter has no such stories.

Get our free weekly newsletter

I’m sitting on a different couch now, watching Christine Blasey Ford and I am ready to be furious. And what I feel — no matter what happens — is gratitude. I am grateful to her for reminding us again —our voices matter, our stories matter, our bodies matter, and that we deserve a world in which we can speak truth to power. Whatever happens, she’s reminding us of this: She’s charging us with the work ahead.

And there is so much work ahead. There were three female senators in 1991. Now there are 23. Maybe soon there will be more. And there must be more. And I know how terrifying what she’s doing is. And she’s doing it for all of us, so that we can find our voices and own our stories and say no more, no more, no more. I don’t know what will happen tomorrow, or the day after, and whether this group of senators will fail this woman – and women – once again. But I keep thinking: Thank you, professor Blasey Ford. I am not going back. We are not going back. There is no way on but through.