Story highlights

Dutch architects are building what they claim is world's first 3D printed house

The 13 room canal house will take three years to construct

Some experts question whether this is an efficient way to build new homes

Almost every day for the past month, a crowd of curious onlookers has gathered in northern Amsterdam to gawp at three mysterious structures.

Measuring 2.5 meters tall high and 1.7 meters wide, the large plastic blocks look like little more than oversized liquorice candy or a confusing attempt at surrealist art.

Appearances can be deceiving.

According to DUS Architects, the Dutch company behind the project, these innocuous black objects are stage one of what will eventually be the world’s first 3D printed house.

It is made using a “KamerMaker” machine, a giant, custom-made version of a desktop 3D printer that produces a material 10 times thicker than normal.

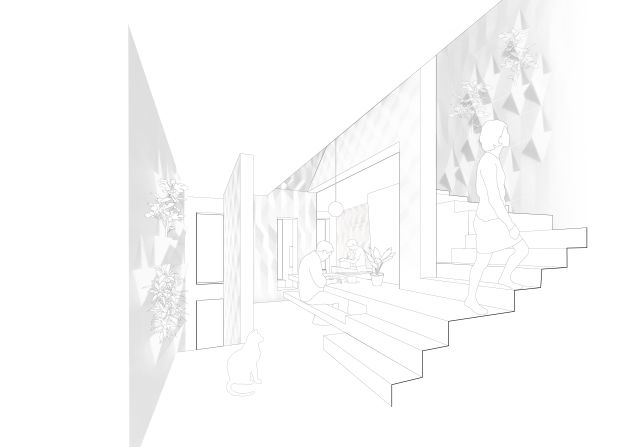

The finished structure will take the shape of a 13-room canal house made from scores of separate but interlocking components (like the three currently on show).

“These rooms will be structural entities on their own. We will then place them on top of each other to make a house,” explained DUS Architects co-founder and director, Martine de Wit.

“Originally, we had the small printers in our office and we were printing scale models with them. Then we thought why not print it (the full house) right away,” she added.

How does it work?

The interior and exterior walls of the house are printed at the same time with spaces left in between for electric wiring and pipes. These spaces are then filled in with concrete for insulation and reinforcement.

As it stands, the primary material being used is a bio-plastic made from 80% plant oil but other substances are being tested for their suitability.

Between six and ten blocks are required to make one room and the entire process of printing and assembling the house is estimated to take three years. According to de Wit, the Amsterdam project is an experiment to test out the feasibility, challenges and cost implications of fashioning a house in this way.

“If you print in plastic you can recycle the materials,” de Wit explained. “We also see the possibility to design something, send it digitally and then print it exactly in the place that you need it rather than transporting everything to the location.”

On top of this, houses can be custom designed to suit individual owners tastes, moved piece by piece to a new location if required before being put together again and only the precise amount of material required would need to be used, reducing waste in the process.

De Wit even sees the possibility of building furniture, arts and crafts into the blocks that make up a 3D printed home. The canal house will feature a printed block containing a staircase.

But while the potential benefits of building a house in this manner may be appealing, there remain many challenges before the technology is proven effective from a structural, living and economic sense.

A note of caution

De Wit is clear that the final costs of the project are still unknown and admits that 3D printing is unlikely to replace existing house building techniques any time soon.

Others, however, doubt whether the concept has any long term value at all.

According to Dr Phil Reeves, managing director of UK-based 3D printing consultancy and research firm, Econolyst, printing a house takes longer and runs counter to existing building techniques which are already relatively efficient.

“A lot of housing projects are using very modular systems of building where things are built in a factory off site, bought and then assembled very quickly,” Reeves said.

“This is counter to that. It’s about much longer times on the building site.”

Reeves also points out the difficulty of altering wiring between walls or correcting faults as they arise after they have been insulated with concrete.

Yet despite these potential drawbacks, de Wit and her colleagues remain hopeful the idea can provide benefits to the architecture and construction industries if the initial Amsterdam project is successful.

“I don’t think we’ll print all homes through 3D printing in future but I think it can be an additional, valuable tool to what we already use,” de Wit said.

See also: London’s insane luxury basements