Story highlights

Millions of young people sent from city to country during China's Cultural Revolution

Under Mao Zedong, the Communist Party was purged of "bourgeois" elements

Hu Rongfen was a middle school student sent away from her home in Shanghai

Hu: "We were told that city dwellers never move their limbs and could not distinguish different crops"

Hu Rongfen had no choice. On November 14, 1971, in the whirlwind of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, the slender and soft-spoken middle school graduate was dispatched from Shanghai to a far-flung village in East China’s Anhui Province to work in the country.

This wasn’t a punishment for any wrongdoing – on the contrary, the quiet girl was a top student in class. The migration was an order from the central government to every urban household – at least one of their teenage children needed to leave the city to work on the farm indefinitely.

The ruthless political command lasted from 1966 until the mid-1970s and intended that the privileged urban “intellectual” youth learn from farmers and workers. As a result, China’s “lost generation” emerged – deprived of the chance of education and the right to live with their families.

“We were told that city dwellers never move their limbs and could not distinguish different crops,” says Hu, now 58. “So we were banished to labor and learn skills and grit from peasants.” Hu spent four years (1971-1974) planting rice, spreading cow dung and chopping wood in Jin Xian, a mountainous county.

Read: Consuming Cultural Revolution in Beijing

Known in Chinese as “up to the mountains and down to the farms,” the urban-to-rural youth migration was part of China’s decade-long Cultural Revolution, a social political movement initiated to implement Communism and Maoism in China by eliminating any capitalist, feudalistic and cultural elements.

Hu still remembers the luggage she brought: basic life necessities, the “Little Red Book” explaining Chairman Mao’s theories – a mandatory read for everybody – and dozens of notebooks with hand-copied chapters from “Jane Eyre” and “Anna Karenina,” which she sneaked in secretly – these books had been banned for their perceived Capitalist connotations.

“I used to read those notebooks in secret under my blanket at midnight.”

According to Chinese media, as many as 17 million “intellectual youths” in the country packed their bags and moved to some of the remotest parts of China. There, they transformed from care-free students to farmers.

“I still can’t bear to recall my youth spent on the farm,” she says.

One of Hu’s most vivid memories was working in rice fields in early spring in freezing water, on which lumps of ice still floated. There, she would bend down to seed for more than ten hours. She would slap her legs madly to rid herself of the leeches clinging to her limbs. Blood would ooze from her wounds and mingle with the dirt and water.

Another time, she recalled walking 40 kilometers along mud paths against bone-chilling winds to the nearest bus station on Chinese New Year’s Eve to catch a ride to the train station to go back to Shanghai to see her parents.

Hu was eventually elected by her commune to study mechanics at a college in Hefei – the capital of Anhui – in 1974. Most people stayed as long as eight years in their commune and only started returning to cities from 1978 onwards. Many did not get a chance to return to their studies.

Hu eventually found a job in Hefei after graduation and lived there until 1986 before moving back to her hometown for good. She worked as an office secretary at a scientific laboratory in Shanghai until her retirement in 2008.

But the memories from her youth still make Hu blanch.

“If the Cultural Revolution came back and I were to be dispatched again, I’d rather commit suicide,” she says, noting that the farming days tortured her physically and mentally. “I stayed awake night after night at the commune, worrying if I’d ever return to any city.

“After my retirement, I seize every opportunity to travel and exercise my body (to stay healthy),” she adds.

“I live a happy life now. I want to live every day like (I were still in my) youth because I was never able to enjoy my teens and 20s – the best time of one’s life.”

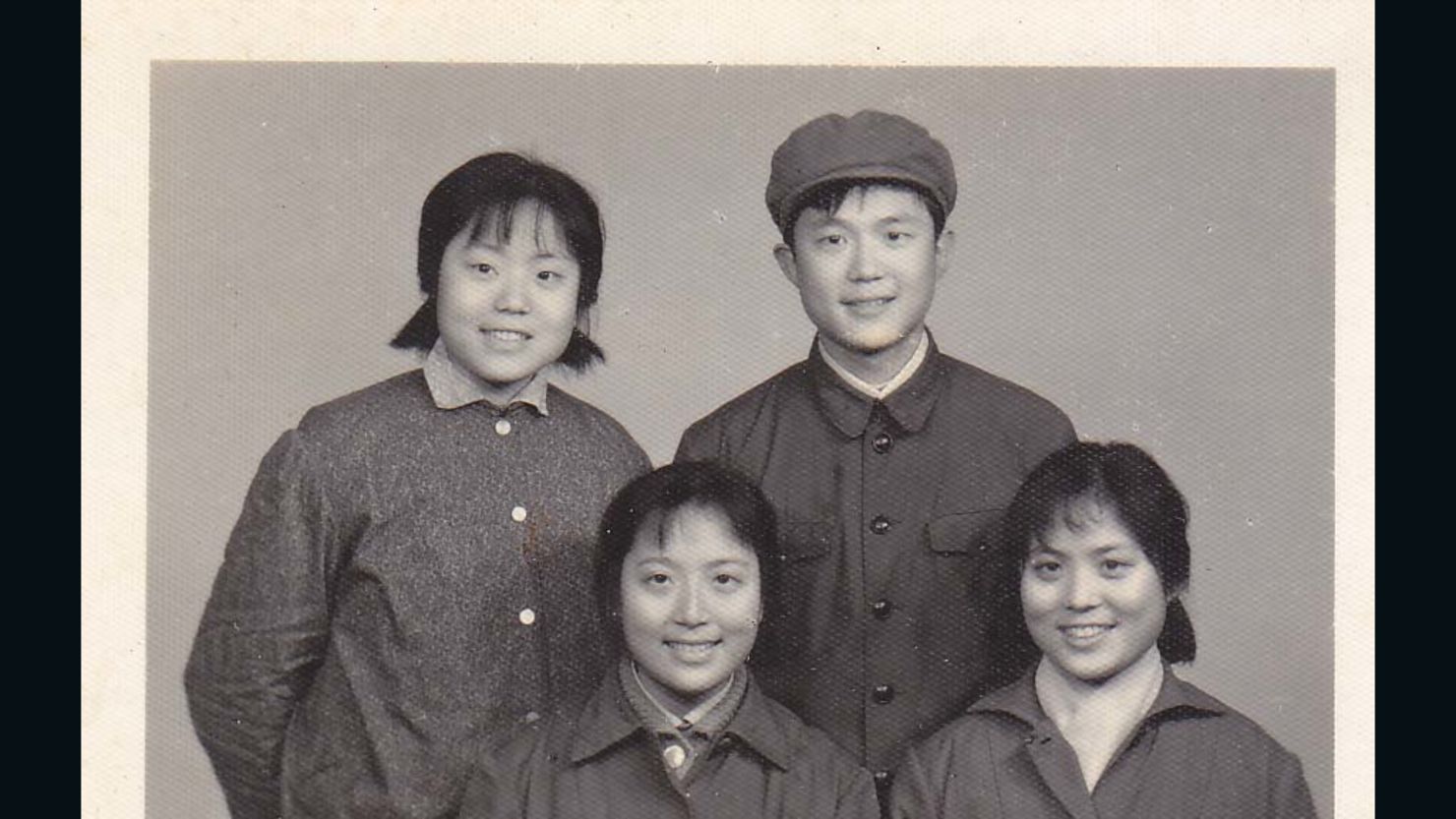

However, she confesses she did gain something – an iron will to live through the toughest conditions and four lifelong friends.

Hu and her four dormmates on the farm have stayed in regular contact for the past four decades. Having experienced similar ordeals in youth, they encourage and support each other to enjoy the present and the future. They write memoirs, travel stories and nostalgic poems to share with each other or post to the web.

“It’s a way for us to act out our feelings towards the past,” she says.

“Together my ‘comrade sisters’ and I lived through some unimaginably tough times – learning to live without parents and like peasants,” says Hu.

“And now we want to live our youth again all together.”

As Leo Tolstoy wrote in “Anna Karenina”: “All the variety, all the charm, all the beauty of life are made up of light and shade.”