Editor’s Note: Molly Crabapple is an artist who has created work for the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Royal Society of Arts, Red Bull, Marvel Comics and DC Comics. She also contributed to CNN’s ‘Power’ gallery. She was among those arrested on Monday during a rally to mark the one-year anniversary of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Read more about the day. Follow her on Twitter: @mollycrabapple

Story highlights

Molly Crabapple: I was arrested for taking part in an Occupy Wall Street rally

Crabapple: I was inspired to see people care passionately about inequality issues

She says getting arrested for a social protest is like being put through aversion therapy

Crabapple: The movement won me over, I would protest again

We were not the first round of protesters this prison cell had seen. On the beige walls, former residents had scratched “OWS,” “love” and an expletive about the police.

At 1 Police Plaza in New York City, our cell was 5-by-7, freezing cold, with a padded bench just long enough for three of us to sit on. A fourth woman was curled on the floor. In the corner, there was a non-functioning sink and a toilet. When one woman needed to use it, we formed a line to block her from the male officers. In the 10 hours I was held, there was one meal: Four slices of bread in soggy Saran wrap, a packet of mayo and a mini carton of milk.

Last year, Occupy Wall Street happened outside of my window. As a local, I was supposed to deplore those “dirty hippies.” But I found I couldn’t.

See Crabapple’s art in CNN’s digital gallery

At the time, I made my living drawing for ferociously swanky nightclubs while watching the world crumble and people from Tahrir Square to London take to the streets. Everyone said that Americans were too apathetic for that sort of thing. Occupy Wall Street proved them wrong.

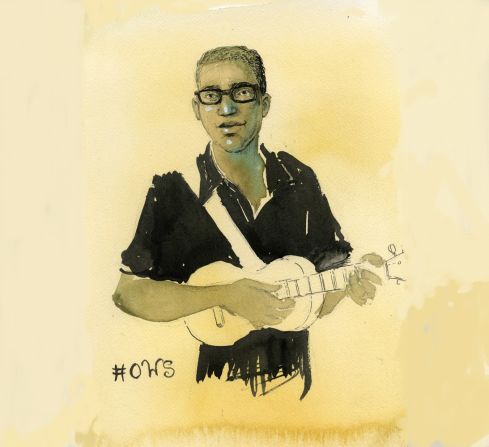

While I was initially skeptical, Occupy soon won me over. Across the street, Zucotti Park had transformed into a mini-city where anyone could get a book, a meal and basic medical care for free. I was inspired by seeing Americans, of all backgrounds and beliefs, caring passionately about income inequality and financial corruption. I wanted to help however I could.

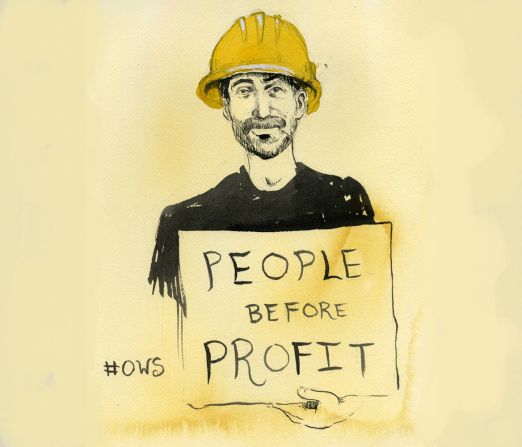

I turned my apartment into a press room, offering coffee and Wi-Fi for journalists filing copy about the young movement. I donated money and marched in protests. While I have been political before, I never let it seep into my artwork. Now I created posters, some of which ended up on the streets as protest signs hours after I uploaded them to the Internet. These posters remain some of the work of which I am most proud.

But that was 2011. This is 2012.

On the morning of my arrest, I wasn’t sure whether the Occupy Wall Street movement was over. I went to the demonstration out of loyalty and nostalgia for the days of the Zucotti camps. The people’s library, free clothes and gourmet soup kitchen were gone now, or reduced to shadows of their former selves. But I wanted to pay homage to the movement that had brought out more of my artistic voice.

At seven in the morning I was on the sidewalk outside my apartment, tweeting pictures of the marchers and police. The NYPD had turned lower Manhattan into a mess of checkpoints. In that way, they were ridiculously effective at disrupting traffic. There were hundreds of cops – some in riot gear, some on horseback. There were trucks piled high with metal barricades.

We just walked. Some were on the street, most like me cautiously stayed on the sidewalk. We shouted the shopworn protest chants that feel so meaningful when you’re chanting them.

At one corner, I saw a cop grabbing the arm of a woman in front of me and pulling her into the street. It was the same gesture you might use to escort an old lady, and, when the next officer did this to me, that is what I thought it was. But then, halfway across the street, he cuffed my hands behind my back.

There was no warning. No Miranda rights like in the movies. At first, I was incredulous. It was not until I got my desk ticket that night for blocking traffic that I had any idea what the officer was accusing me of doing.

I was a head shorter than the officer. I said to him, “You know I was on the sidewalk.” He wouldn’t meet my eyes. I was two blocks from my apartment. But because I was part of a protest, I was no longer a local. I was an obstruction to be cleared.

Going into the police van, they snapped my picture on a Fujimax Polaroid knockoff, hipster party style. I gave them my best grin. A man in a suit passed by, looked us over, and said to the police, “nice work.”

In the van, there were eight people, including an elderly nurse and a legal observer in his official green cap. We had all been plucked off the sidewalk.

The van door shut. I edged my cell phone out of my purse, texted friends about my arrest and then, bored, began dissecting the situation on Twitter. I regretted being such a random little duck, pointlessly arrested to stop the protests.

In the police yard, we traded our bags for vouchers. We waited to have our pockets searched while our shoulders ached from an hour in zip-cuffs. The woman in front of me had wrist injuries. The searching officer yelled that her wrist braces were weapons and threatened to send her through central booking – “the tombs” – where everything took twice as long and was covered in filth.

Jail is waiting. Depressing waiting. Humiliating waiting. Pointless, tedious waiting in a crowded cage with dead roaches and no running water, where officers processing you through the system laugh at your discomfort and fear. The women sang songs to pass the time. “Solidarity Forever.” “The Sun Will Come Up Tomorrow.” The booking officer screamed she’d send us all to the tombs if we didn’t shut up. We sang anyway.

Time seemed interminable. Soon you find yourself banging on cell bars in unison, amplifying the voice of protesters who needed medicine, or who didn’t get their phone calls for eight hours. When the male prisoners burst into cheers, we shushed each other and grinned.

I was the last person released from my cell. The woman who left before me, a middle-aged lawyer who had been arrested multiple times that weekend, reassured me that I’d get out soon. When I did, friends were waiting with hugs, pizza and the National Lawyers Guild. Occupiers have a strong support system for those who are arrested, whether it’s in the form of food, drinks or a pro bono lawyer. I felt incredibly lucky, essentially a tourist in that miserable place. In the pizza joint across the street, we bought beer for a woman who’d been held for 38 hours.

While I was alone before my release, pacing back and forth, it was almost impossible not to suspect that I was stupid, that my actions were futile. Which is the point of an arrest. Getting arrested for a social protest is like being put through aversion therapy, a punishment in and of itself. A relative of mine, an Occupy supporter, said that after my arrest, she’d never protest again. And that’s the point.

Me? I’d be back.

Occupy Wall Street taught many middle-class white people what poor people and people of color had already known. The law is often a hostile and arbitrary thing. Speak too loudly, stand in the wrong place, and you’re on the wrong side of it. My experience was infinitely easier than most. Many people arrested came out to a lost job, or they have to deal with nerve-damaged hands from being in cuffs for too long, or they face a society that believes they asked for it.

While we were in the cell, after we banged too long and chanted too hard, an officer stared at us. “Look at you people,” she said. “What do you hope to accomplish? You brought this on yourselves.”

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Molly Crabapple.