Editor’s Note: Judith Drotar has worked for the past 18 years with multicultural educational communities to develop more tolerant global citizens. After serving as director of the American School of Tripoli for four years, she and her fellow teachers had to leave Libya in 2011 amid the revolution. She is currently working in Doha, Qatar.

Story highlights

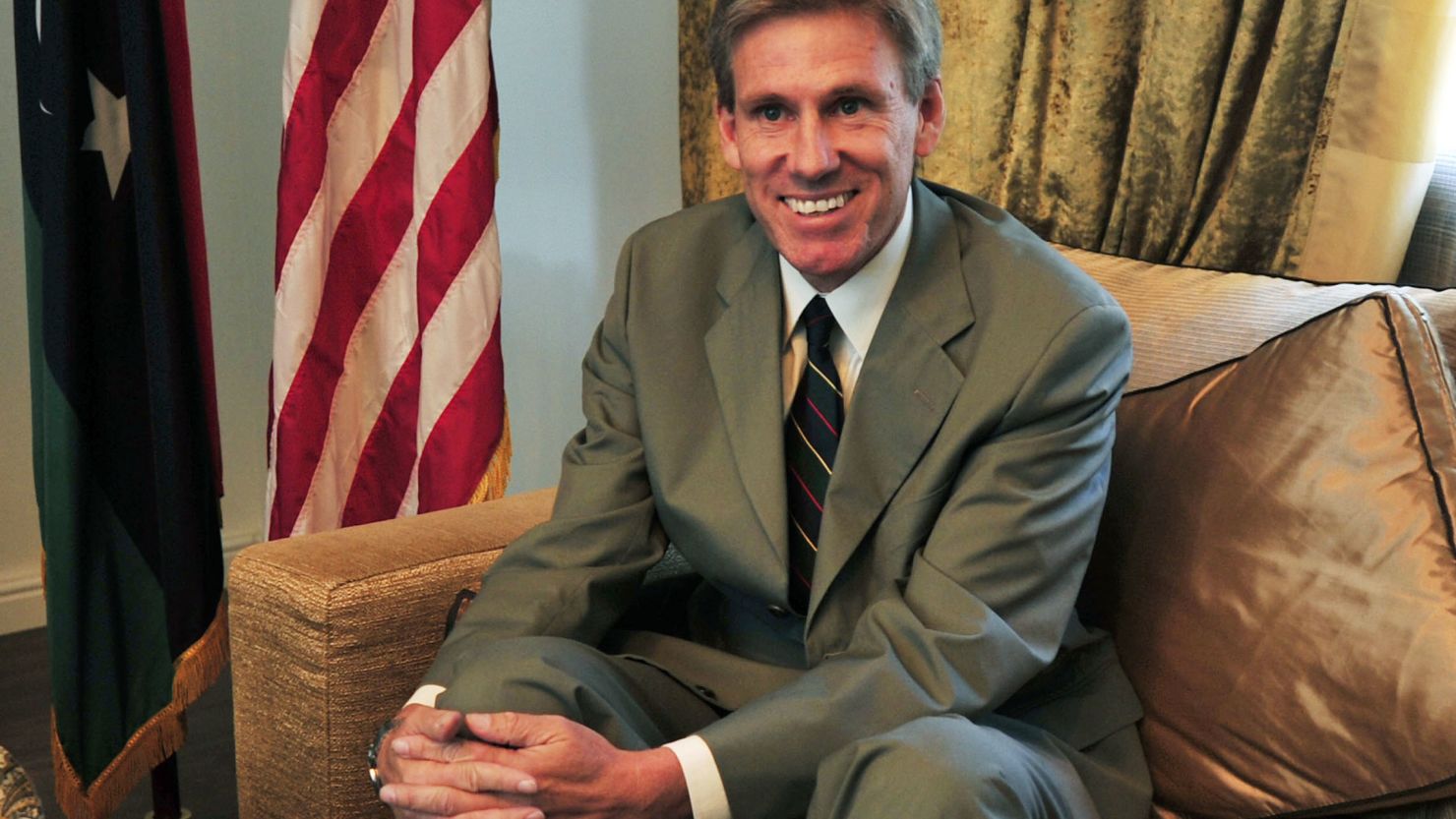

Judith Drotar knew Christopher Stevens when she worked at American School of Tripoli

She says he was kind, smart, approachable and had passion for helping U.S.-Libya relations

She says they met when he was Deputy Chief of Mission; he helped her establish the school

Drotar: He had rare talent for listening, building bridges. His killing a profound loss

It has been three days since Chris Stevens and three other Americans lost their lives in Benghazi, Libya. I lived and worked for four years in Libya, leaving hurriedly last year in an evacuation as the civil war began. I sit safely now in my new home in Qatar, and those who shared my Libyan experiences – and who knew Chris – are now spread out around the world. I know from their e-mails that, like me, they are also unspeakably sad.

Every life on this good earth is precious, and all four Americans who lost their lives at the U.S. Consulate were in Benghazi to help the Libyan efforts. They will be very, very much missed.

Because I knew and worked with Chris, I understand firsthand that the world has lost a true hero, and we seem to have precious few of those. Chris was smart, supportive, kind, approachable, very passionate about reestablishing a relationship between the United States and Libya and improving the lives of the Libyan people. He was a perfect candidate for his new role as ambassador. When someone like that is taken away, you don’t just mourn the loss of a colleague or friend, you mourn the greater loss for our planet.

We were both originally from northern California, but Chris and I first met in Libya, arriving around the same time in 2007. I was there as the new director of the fledgling American School of Tripoli and Chris had just been appointed U.S. Deputy Chief of Mission. The United States and Libya had reestablished diplomatic relations in 2004, but the U.S. Liaison Office had just been upgraded to a full embassy in 2006. Because no ambassador had yet been named, as deputy chief, Chris served as acting ambassador until the arrival of Ambassador Gene Cretz in January 2009.

Working in Libya at that time was challenging. The infrastructure that the West left behind had long disappeared during the 30 years of sanctions, and we were all scrambling to develop our institutions and businesses from the ground up. Chris built a team of embassy personnel, negotiated with a quixotic Libyan government, helped the returning U.S. companies and served as chairman of the Board of Trustees of the American School.

News: U.S. intelligence warned embassy in Egypt of concern about anti-Muslim film

He loved the school and in an e-mail earlier this year shared how much he was looking forward to witness its eventual reopening.

During the two years we worked together, I watched Chris serve with aplomb, patience, and an easy smile. If you sat and talked with him, it was clear that he was well-read and a deep thinker, but he was always humble.

He was also extremely comfortable whether he was speaking with VIPs or Libyan farmers. I had the good fortune to sit with him on the Fulbright Scholarship Committee that helped Libyans further their education in America, one of the many tangible ways he demonstrated his dedication to the Libyan people.

He traveled across the sparsely populated country savoring the rich archaeological sites, and broke bread with Berbers in their cave homes. Always gracious, he hosted receptions for Libyan ministers and businessmen and, just as often, was in khakis and a T-shirt, holding informal embassy gatherings on the roof of his villa, smiling and making sure that everyone was included.

What really made Chris exceptional to me, however, was his ability to distance himself. Not the aloof kind of distancing that you might expect from someone in his position, but the kind where one puts emotion and ego aside in order to truly listen, to understand, and then to find a way to build bridges. It is extremely rare to find someone who can do that, consistently rising above the fray, and that’s what makes his death so especially painful.

Of course I feel anger at those horribly misguided people who are responsible for this tragedy, but I am also trying to rise above it, like Chris would. For those who find this yet another reason to vilify Muslims, I point to other examples of seemingly senseless violence like the Aurora movie theater shootings or the attack on Gabrielle Giffords, neither of which had anything to do with Islam.

We live in a world where frustration and anger override the sanctity of life. We live in a world where it’s easier to get our hands on weapons than to give each other a helping hand. We live in a world where too many people use religion as a vehicle for hatred, rather than love.

I was extremely fortunate for a few years to have lived and worked under the light of Chris’ grace and vision. I know he touched all who knew him. As I continue to watch the Libyans, who have only known oppression, try to dig out of the void left behind in the wake of Moammar Gadhafi’s fall, I will always remember Chris and the legacy he has left them.

We are all better for having known Chris. My hope is hope that Libya will flourish for its people and that we, each in our own way, will make him proud.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Judith Drotar.