Editor’s Note: Touré is an American music journalist and cultural critic who has been writing about Black identities for over two decades. He is the author of “Who’s Afraid of Post-Blackness: What It Means to Be Black Now.” The opinions expressed in this article belong to the author.

The upcoming Sotheby’s auction dedicated to hip hop artifacts – the first of its kind for the auction house – is brimming with totems that transport you back to the music and culture’s early days.

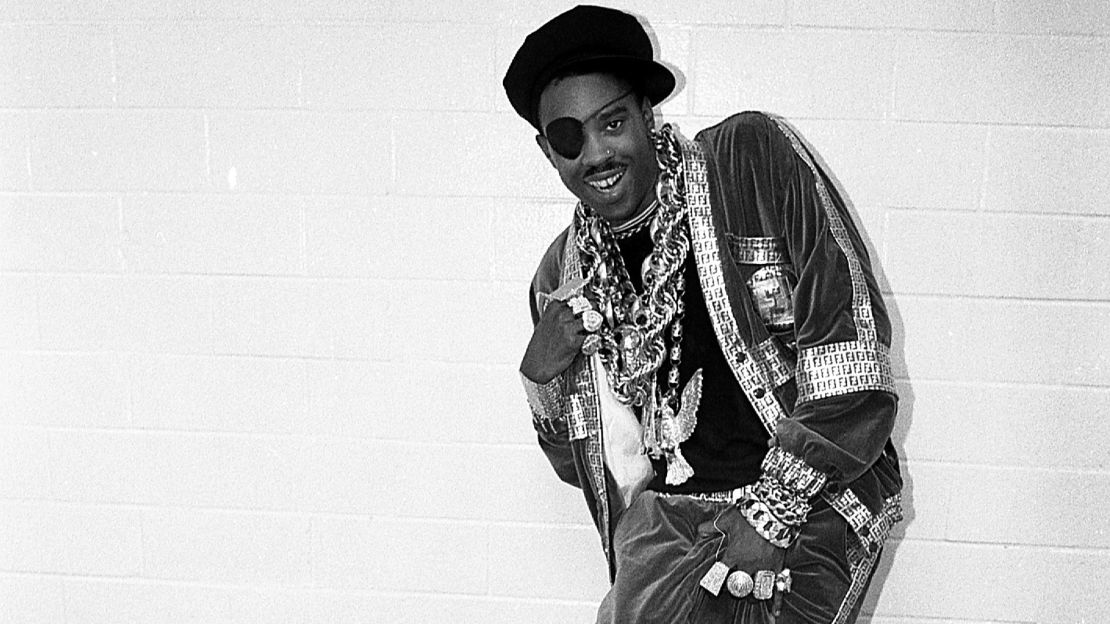

You can bid on flyers announcing concerts from the late ’70s and early ‘80s headlined by the likes of Grandmaster Flash and The Funky 4 MCs, once-coveted jackets bearing the logo of Def Jam Records – the first home of LL Cool J, Public Enemy and the Beastie Boys – or a diamond eye patch worn by the legendary MC Slick Rick. This impressive collection includes classic pieces evoking hip hop’s connections with graffiti, its obsession with sound equipment and its followers’ way with fashion.

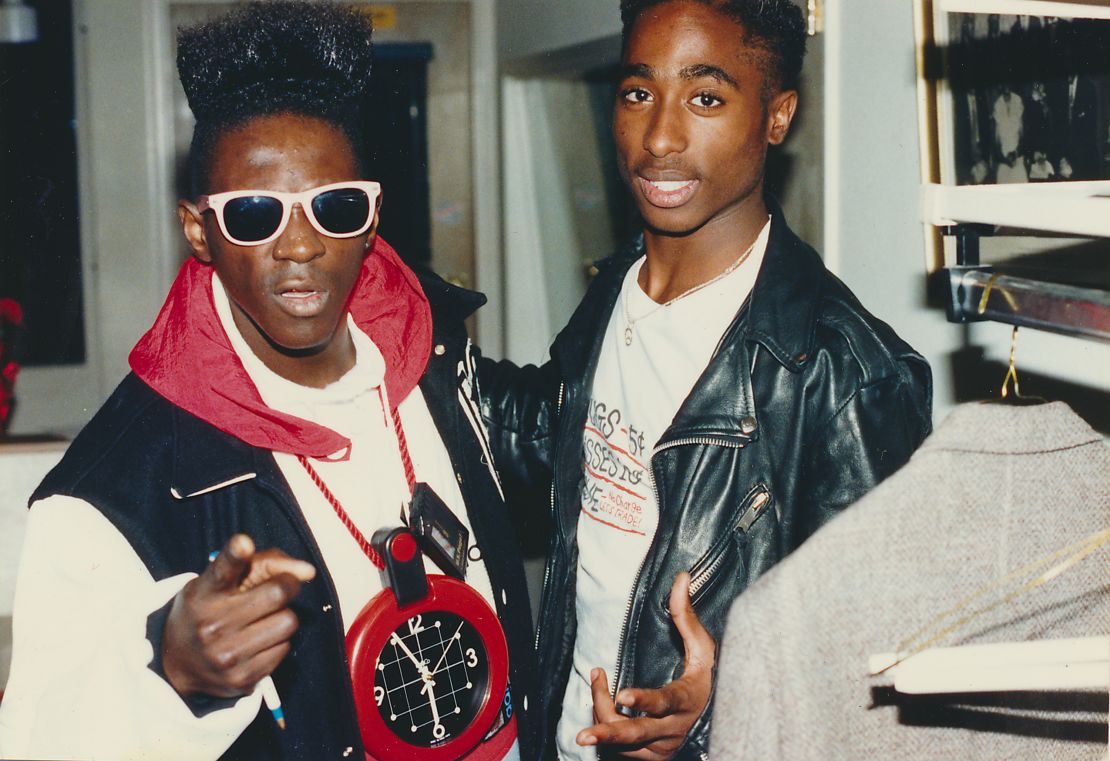

There are also two very special pieces from the ’90s. The crown worn by The Notorious B.I.G. in the final photo shoot taken before he died, and love letters written by a teenage Tupac Shakur. More on those in a minute.

Young Americans

The idea that classic hip hop culture could be significant to Sotheby’s seems somewhat ironic. Back when rappers were wearing these now-auctionable items, those who valued Sotheby’s as arbiters of taste would likely have dismissed hip hop in the same breath.

When hip hop was a new, revolutionary New York subculture, many Americans were scared of it – they were worried it was going to ruin the young generation. I was a part of that young generation, and I loved hip hop from the first time I heard “Rapper’s Delight.” I loved going to the record store and buying the latest cassettes from Run-DMC, LL Cool J and Kurtis Blow.

Of course, much of the older generation that thought I and other hip hop-obsessed kids would end up as criminals or gang members had loved rock n roll when they were younger, and had been told by their elders that that music would ruin their lives. But as adults they were scared of this new Black urban sound and style – so much so that in the early ’80s the mere hint of a hip hop beat and the sight of a breakdancer in a Kangol hat could make many clutch their pearls and run across the street for safety.

These days, hip hop is a global phenomenon with none of that fear-inducing potential. It is the mainstream: The house band on the Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon is hip hop group The Roots. McDonald’s has a new commercial featuring rapper Travis Scott promoting the combo meal that bears his name. Kanye West is no stranger to the Oval Office, just as Jay-Z and Pulitzer Prize winner Kendrick Lamar were White House visitors during the prior administration. Now that hip hop has become an institution, it makes sense that an institution like Sotheby’s is ready to immortalize its early days.

From the comfortable remove of nearly five decades, it’s much easier to see hip hop’s importance.

Kings and poets

For many current fans, most of the items up for auction might represent a moment that has almost nothing to do with the culture they know now.

Still, the two items on the auction block that connect lovers of this music today to its history are the artifacts from Biggie and Tupac, two men who remain at the spiritual core of hip hop. You still regularly hear their names in rap lyrics, and I’ve seen shrines to Tupac in many rappers’ home, while Biggie’s face is painted on walls all over Brooklyn.

The crown Biggie wore in a photo shoot – cocked to one side like a baseball cap – that took place just three days before his death is up for sale. And it brings me back to one of the core messages of hip hop: so many MCs are self-crowned kings.

It’s expected for a rapper to say they’re the best ever. There’s no time for humility in this world. The legendary rapper KRS-One once told me that rap songs are like “confidence sandwiches”: you create them by putting all of your bravado into the music and when someone repeats your lyrics – literally putting the song in his or her mouth – their body is filled with the confidence that the MC felt when they were making it.

Historically, the majority of MCs have been male, and their towering confidence is rooted in the power of the Black male ego, which so many Black men rely on to keep their sanity and their self-esteem intact. The Black male ego isn’t necessarily built on one’s achievements or ability; it’s a shield protecting a man from a world that’s constantly beating him down, telling him he’s worthless.

Biggie’s crown was also special because it represented his place on a unique throne. He was considered the best rapper in New York, at a time when that was like being the Heavyweight Champion of hip hop. It was something that mattered in the ’80s and ‘90s – but means far less now.

As hip hop has grown to be a truly national sport, the throne has grown cold. Gone are the days of hip hop as a competitive field filled with rhyme battles; in this corporate era of hip hop, such passion is a thing of the past. There’s too much money at stake.

Tupac was another self-crowned king MC who had a massive ego, but he also had a big heart. Even though he mostly presented himself as emotionally bulletproof, he also made records about his love for his mother, and rapped about how she had hurt him. It’s nice to see, through the love letters at Sotheby’s, a glimpse of the young, romantic, vulnerable Tupac, who was willing to pour his heart out to a girl he loved. It’s powerful to see a tough man be a softie, and the hip hop love song has been a critical part of the genre – like LL Cool J’s tender, vulnerable record “I Need Love” from ’87.

As it always was

Both Pac and Big were rich and famous when they were shot dead within six months of each other (in 1996-97), victims of gun violence. Their deaths sent hip hop into a mourning that has never really ended. They remain beloved figures and their murders are a reminder that no matter how big a Black man becomes in America, everything he achieves can be taken away in a heartbeat. His success is fragile, and his life is on the line every time he walks out into the street.

While it’s nice to see a renowned auction house like Sotheby’s curating a truly authentic collection of hip hop pieces – just like it was excellent to see the Pulitzer Prize for Music go to Lamar in 2018 – the days of getting excited about hip hop receiving institutional recognition are over; it long ago established its cultural importance. By now if you haven’t recognized hip hop, we should have questions about you. It’s one of the greatest art forms America has ever created.

But what Sotheby’s trove of artifacts does remind me is, it’s not that hip hop has become great, it’s that it always was.

Sotheby’s first hip hop auction, of recent and legacy items, will be held in New York on September 15. A portion of the proceeds will be used to benefit the Queens Public Library hip hop programs and community non-profit Building Beats.