Editor’s Note: Kenny Schachter is an art curator and commentator. The views expressed here are the author’s own.

Would you pay nearly $30 million for a chair; granted, a brown leather and wood, comfy thing with lacquered swirls? That’s was happened when Eileen Gray’s “Dragons” armchair dating from 1917-1919 fetched nearly 21.9 million euros ($28 million) on an estimate of up to 3 million euros at a Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé auction at Christie’s in 2009. The piece stands as the world’s most valuable work of contemporary design. Careful with your crumbs!

There’s a blistering swirl of interest in the financial outcomes of various collecting categories including art, classic cars and design of late. From collector Yusaku Maezawa’s recent acquisition of a painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat for $110.5 million to the purchase of a 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO for $38 million in 2014, we are in an age of collecting kookiness. Yet there is a reason: There are more people looking at, writing about, making and buying art and design than ever before.

According to the 2017 Art Basel and UBS Global Art Market Report, the art market generated $56.6 billion in sales in 2016, down 11% from the year before. In the same year, the car market was estimated at $10 billion by the Historic Automobile Group International (HAGI). In the days of money mania, there are even financial indexes on Porsches and Ferraris.

Though no hard data is available, I’d gather the overall design market is worth substantially less. However, as an alternative to parking cash, investing in art, design and cars has never smelled better.

SWAG (silver, wine, art and gold), the so-called passion investments, should be updated to CAD (cars, art, design). But can you trade with equal opportunities for return amongst these categories?

Since art came off the walls of caves it’s been coveted. Collecting, I’d suggest, is not simply an obsession: it’s genetically programmed. Hunting and gathering is part of the human condition.

The bleak storm of social, political and economic uncertainly only adds to the desirability and safe-haven status of art. And why not art and beautifully rendered objects to help cope? A study at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in London found that exposure to visual art and live music in a trauma and orthopedic ward translated into shorter hospital stays and less medication for patients. That’s not to mention the potential for a monetary return on your investment: the prospect should make you feel better and at least financially healthier.

Where the money’s going

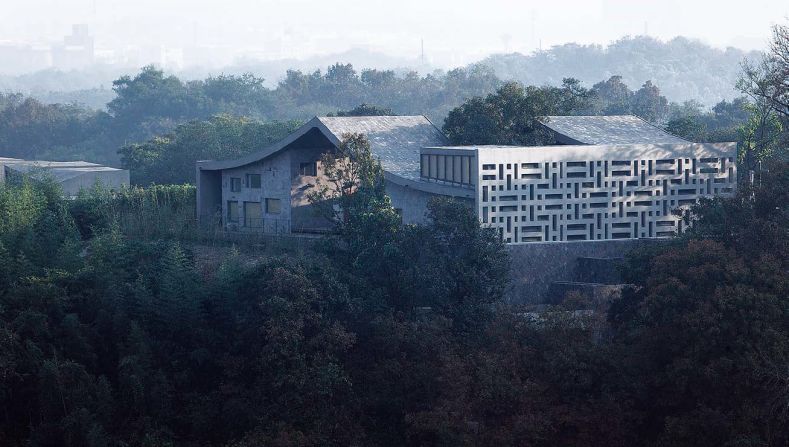

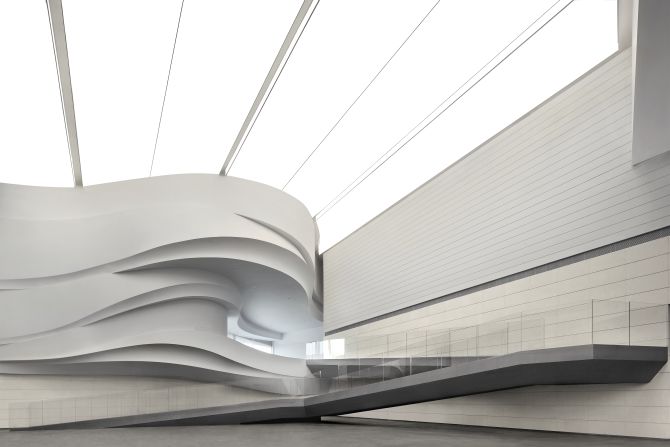

Art museums around China

In the 30 years I’ve been curating, teaching, and dealing art, cars and design (and writing on the markets, and making art too), the two biggest changes I’ve witnessed are the meteoric rise of Asia in Western post-war art- and design- buying (importing a classic car into is a mission fraught with red tape), and Instagram.

Instagram, by default, has changed how art is experienced, exploding geographic boundaries reflecting the global way we think and live. Connecting users by shared interests, Instagram transcends hierarchies and democratizes the way information is accessed and processed. When Instagram is eventually monetized as a transactional platform for art (already well underway) they may be able to devour a chunk of the art world the way Amazon just swallowed Whole Foods.

Per a 2016 report by Larry’s List, a Hong Kong-based art market research firm, there were 317 privately founded contemporary art museums in the world. South Korea had the highest number, at 45, behind the US with 43. (China weighed in at 26, but I can assure you that number will triple in the next five years or less. Watch.)

There is also a shift underway in auction activity by Sotheby’s, Christie’s and even Phillips and Bonhams angling for market share in the gradually opening (though still tightly controlled) Chinese playing field. That Poly Auction, the largest Chinese auction house, is owned by the state puts competitors at a disadvantage. The prohibitive restrictions on the movements of currency outside China is holding back further explosive growth, but I’d also wager that doesn’t last.

Swimming with the sharks

Art seems to have developed a reputation as an unregulated market. This is not the case. In the United States, for example, the Uniform Commercial Code – general statuary provisions that apply to fraud, misrepresentation and authenticity issues – governs commercial transactions of any nature.

But while you’re not altogether standing with your pants down in the aisles of an auction house, be warned: you are dealing with sharks far more ferocious than one suspended in formaldehyde in the vitrine of a Damien Hirst, so beware.

Collecting anything is a slow-burning, incremental process entailing the gradual accrual of information and knowledge. The ability to discern aesthetic wheat from chaff is a lifelong trek called connoisseurship.

I believe every participant, of any stripe, who has succeeded in the art market comes from a point of love. From Larry Gagosian, who runs one of the world’s most successful gallery empires, to Patrick Seguin, one of the foremost dealers of 20th century design, no one enters these fields with the sole desire to make money.

Follow your passion not your purse. There is no way to approach these fields and not get run over (steamrolled may be a more apt description) other than through diligence, prudence and care.

And remember to always check your rearview mirror!